03/31/19-KEEPING HOOVED ANIMALS OUT OF ʻŌHIʻA FORESTS HELPS REDUCE SPREAD OF KILLER FUNGUS

Posted on Mar 31, 2019 in Forestry & Wildlife, Invasive Species, sliderNews Release

| DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR |

SUZANNE D. CASE

CHAIRPERSON |

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 31, 2019

KEEPING HOOVED ANIMALS OUT OF ʻŌHIʻA FORESTS HELPS REDUCE SPREAD OF KILLER FUNGUS

West Hawai‘i Community Talks Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death

To view video please click on photo or view at this link: https://vimeo.com/327586410

(Kona, Hawai‘i) – The people leading research and management of the fungal disease known as Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death revealed their latest scientific findings and management tools to interested people at a community forum at the West Hawai‘i Civic Center on Saturday. Billed as a Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death Symposium, the seminar was the second of two held this year on Hawai‘i island which has seen hundreds of thousands of acres of native ʻōhiʻa forest impacted by the fungal disease. Among the revelations a couple of dozen participants heard, reinforced the notion that keeping hooved animals (ungulates) like cows, goats, sheep, and pigs out of forests helps them stay healthy.

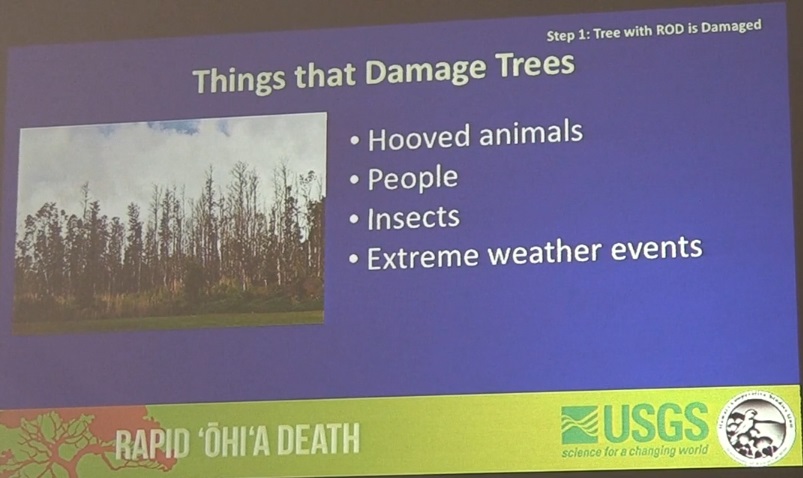

Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, or ROD for short, enters trees through wounds to its bark. Researcher Kylle Roy of the U.S. Geological Survey explained that animals rubbing on the trunks or browsing on the bark or digging at the roots can create wounds. This exposes the sapwood and can damage the roots, allowing fungus spores to grow on the wound.

Fencing native forests is a common method for keeping ungulates out of them and preventing damage to sensitive watershed areas. Until recently the benefits of fencing for keeping ROD at bay had not been clearly shown.

Dr. J.B. Friday of the University of Hawai‘i’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR) showed research from Dr. Flint Hughes with the USDA Forest Service and Dr. Greg Asner with Arizona State University that demonstrates the linkage between fencing and stopping the spread of Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death. Based on aerial surveying and on-the-ground sampling of fenced and adjacent non-fenced land in several areas around Hawai‘i island researchers can show that areas protected by fencing have much, much less suspected ROD infestation than areas that are open.

Friday showed several slides, punctuated with red dots that have been shown to be infected with ROD and a blue line that denotes a fence. On one side (fenced) only a few red dots are seen. On the other (non-fenced) the red dots created a nearly solid mosaic of color.

He explained that fencing only works to help prevent the spread of ROD when ungulates are removed from the area. “One of the things that’s worse than fencing the area,” he commented, “is fencing an area and leaving the animals in.”

DLNR Chair Suzanne Case said, “This is another reason for Governor Ige’s commitment to fully protect 30% of our critical forest watersheds by 2030. Fencing is a critical part needed to make this vision reality.” DLNR First Deputy Robert Masuda added, “Scientists, researchers, land managers and hunters are continuing to work collaboratively on ways to stop the spread of this disease.”

The symposium also included presentations on screening and resistance, tree and wood treatments, forest effects and aerial surveying, management actions and outreach efforts. It also included a community input session where small groups discussed the five things individuals can do to help stop Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death:

- Avoid injuring ʻŌhiʻa

- Don’t transport ʻŌhiʻainter-island

- Don’t move ʻŌhiʻa

- Clean your gear/tools

- Wash your vehicle

A large group of government, non-profit organizations, and private land-owners continue a years-long collaboration to try and stop Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death’s spread and to try and figure out potential treatments. The two species of fungi that cause ROD, identified on Hawai‘i island four years ago and more recently on Kaua‘i are new and previously undescribed anywhere in the world. species. Ōhiʻa is considered Hawai‘i’s most important native tree for its ability to protect critical watershed areas as well as for its cultural significance.

# # #

Media Contact:

Dan Dennison

Senior Communications Manager

(808) 587-0396

[email protected]