Palila

Loxioides bailleui,

Endemic,

Critically Endangered

Found only on the upper slopes of the largest mountain in the world, Mauna Kea, the critically endangered Palila has a vibrant yellow head, a strong bill, and a delightful call. This spectacular bird is an important part of our Hawaiian heritage worth protecting.

“…E aha ana lā Emalani?

E walea a nanea a‘e ana

i ka leo hone o ka Palila,

ʻoia manu noho kuahiwi….”

“…What is it that Emalani is doing?

Relaxing and enjoying

the sweet voice of the Palila,

those birds that dwell upon the mountain….”

(from the 1882 song “He Inoa Pii Mauna no Kaleleonalani” about Queen Emma’s visit to Mauna Kea)

“Why are Palila special?”

Palila are endemic, occurring only in Hawai‘i and nowhere else in the world. They are a classic example of the spectacular evolutionary process that occurred in the remoteness of the Hawaiian Islands where they survived in the dry forests for well over 100,000 years by adapting to a food source, māmane (Sophora chrysophylla) pods. The speciation that occurred in Hawai‘i dwarfs what was made famous by Charles Darwin in the Galapagos Islands where 14 species evolved from an original species. In Hawai’i, there were 55 species that evolved from the original species, most likely a Eurasian rosefinch that arrived from Asia. Palila belong to a group of birds called the Hawaiian Honeycreepers, which also includes ‘i‘iwi, ‘amakihi, and ‘akiapōlā‘au. Many (38 out of 55) of the palila’s relatives in this family have already gone extinct. In fact, of the 16 finch-billed Honeycreepers (species with heavy, seed-eating bills similar to the palila’s bill) that are known from the main Hawaiian Islands, all have gone extinct except the palila. Māmane trees provides over 90% of the food in the diet of palila, making them a specialist and highly dependent on māmane trees for their survival. Similar to the soybean pods that we eat, māmane trees produce pods with highly nutritious seeds for palila to eat. Interestingly enough, these seeds are poisonous to other wildlife. Their dependence upon māmane makes them an indicator species of the high-elevation dry forest, helping us monitor the health of the forest that they depend on. The decline of the palila population highlights that the forest is not healthy. The last remaining individuals are confined to a small portion of Mauna Kea. DLNR and their partners (The American Bird Conservancy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Arbor Day Foundation, and hundreds of volunteers) are collaborating to restore māmane forests on Mauna Kea. We are fortunate to have the opportunity to restore the forest they depend upon in anticipation of a brighter future for this native bird. Palila belong here and are one of the things that makes Hawai‘i one of the most amazing places on the planet.

The Hawaiian Honeycreepers evolved from one ancestor into many diverse beak shapes, one of which includes the palila [image from “The Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Drepanidinae” by Douglas Pratt (2005)

Palila are the last of the finch-billed Hawaiian Honeycreepers left on the Main Hawaiian Islands. [image from “The Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Drepanidinae” by Douglas Pratt (2005)

“Ecology—all about palila”

As one of the rarest bird species on the planet, palila are found nowhere else in the world, but a small area on Mauna Kea. They are part of the diverse Hawaiian Honeycreeper group that includes the curved-billed ‘i‘iwi, scarlet ‘apapane, and parrot-like-billed kiwikiu. Distantly related to finches, the palila represent the last of the finch-billed seed eating birds in the main Hawaiian islands.

Plumage

- Yellow head – Males typically have yellow feathers that extend down the back of the skull to the neck, or nape line. On females, this area usually has more grey feathers similar in color to the feathers on their upper back.

- Gray back and whitish belly

- Black bill on adults; yellowish bill on fledglings

- Wing bars (white feathers that look like white stripes) on the wing feathers (median and greater coverts) are used to determine if juveniles are 1-year (1 wing bar) or 2-years old (2 wing bars).

Size

- Length: 7.5 inches tall

- Weight: 1.3 ounces

Food

- Māmane provides over 90% of the palila’s diet. Palila eat the immature seeds, flower parts and nectar, young leaves and buds, and caterpillars in the seeds.

- Fruit from naio trees are the second most common food eaten by palila. It accounts for less than 10% of their diet though.

Reproduction

- Low reproductive rates

- The females select the nest site and the male helps her build it. Nests are not reused in following years.

- Average number of eggs laid per nesting attempt is 2 with a range of 1-4.

- One egg laid per day.

- Incubation lasts 17 days on average and female does all of the incubation.

- Nestlings typically start flying, or fledge, at 25 days old. Parents continue to feed fledglings for up to four months after the fledgling begins to fly.

Movement Patterns

- Fledgling palila typically spend their entire life within 3 miles of their nest tree.

- Adults have small home ranges of ~ 750 acres.

- The most noteworthy movement pattern of Palila is the movement between higher elevation and lower elevation sites of suitable māmane forest as they track the availability of the primary food source, māmane flowers and pods. At one part of the year, trees at higher elevation produce flowers and then pods, providing a year-round food supply. During the other part of the year, trees at lower elevations produce flowers and then pods. Maintaining this large elevational gradient is essential for the survival of palila. They now occupy <5% of their original distribution on Hawai‘i Island and this area is the only remnant of their habitat that still provides the year-round food supply they need.

Survival and Abundance

- 1st year of life = 36% survival

- 2 years and older = 64% survival

- Oldest known palila in the wild = 17 years

White wing bars are characteristic of the juvenile stage of palila.

Immature green māmane pods and seeds are the palila’s favorite food

Close up of toxic green māmane seeds that palila depend on.

Palila nest with egg and newly hatched chick.

Palila chick being fed by parent.

Chicks are fed larvae found in māmane pods.

2012 population estimate: 1,749 – 2,640 Over the past 10 years (2003-2012) the population decreased by approximately 66%.

“Māmane—food of the palila”

[three_fourth] Māmane (Sophora chrysophylla) is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. It is the dominant tree in the high-elevation dry forest of Mauna Kea. Māmane is in the Fabaceae (pea and bean) family. It can grow in the form of either a large shrub or a tree with some trees over 40 feet tall. Bright yellow flowers grow on māmane produce pea pods. The seeds contain toxic chemicals called alkaloids. The elevational range of māmane has been reduced on both ends by human conversion of forest for agriculture and by nearly 200 years of browsing by non-native ungulates. It now occurs as low as 5,800 feet in some areas to above 10,000 feet at the highest elevations. Immature, green māmane seeds are the main component of the palila’s diet, although they also eat flowers and leaf buds. Native caterpillars found in the pods eating māmane seeds are protein-rich and an important food source for the quick-growing nestlings and fledglings. Māmane trees growing across a large elevational range are a good indicator of suitable palila habitat, and currently palila occur where the elevational distribution of the māmane forest is greatest. This is because māmane trees at lower elevations produce flowers and pods at one part of the year, and then later in the year trees at higher elevations produce flowers and pods. Thus, the result is a year round food supply—an important characteristic for a bird with a small home range.Māmane is the main tree of Mauna Kea’s high-elevation dry forest.

It is said that the māmane would bloom in such quantities that from Hilo, it looked like Mauna Kea was adorned in a lei.

Traditional Hawaiian house complex often built with māmane wood.

The hard, durable wood of māmane was used by the Native Hawaiians for pou (house posts) and kaola (beams) up to 2.0 in in diameter, ʻōʻō (digging sticks), ihe (spears), kope (spades), papa hōlua (sled) runners, papa olonā (Touchardia latifolia scrapers), ʻau koʻi (adze handles), and wahie (firewood). Cattle ranchers later used the wood as fence posts.

Queen Emma names William Lindsey’s son in 1882

“…when Queen Emma went to [Mauna Kea and the lake] Waiau, she told my father that she wanted my mother to go as well. My father told her, she was pregnant, pregnant with me. But she wanted a woman to accompany her…. Queen Emma told my father, ‘if a son is born, name him Ka-hale-lau-māmane’ {the māmane-leafed shelter}….[When they traveled up Mauna Kea,] they broke the māmane branch, and made a house. You can go hide underneath, and you donʻt get wet.”

–James Kahalelaumāmane Lindsey, 1966;

(excerpt from Mauna Kea, ka piko kaulana o ka ʻāina)

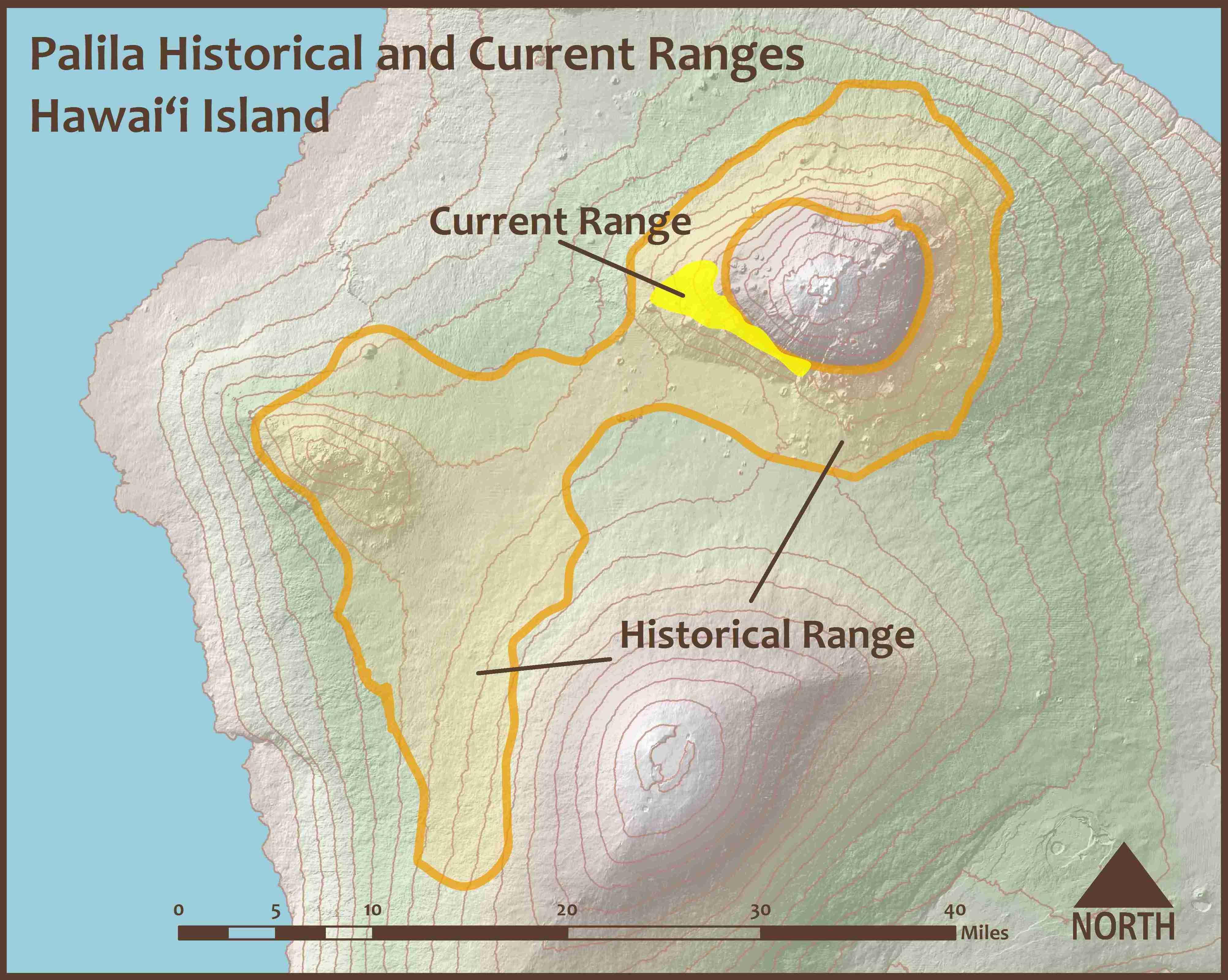

“Distribution—where palila live”

Historically, palila occurred on the islands of Hawai‘i, O‘ahu and Kaua‘i. On Hawai‘i Island, they inhabited the māmane forests on Mauna Kea, Hualālai, Mauna Loa and the saddle area in between. Today though, palila only live on a very small part of Mauna Kea’s southwestern slope where contiguous māmane forest still occurs between the elevations of 6,600 to 9,600 feet. This area represents less than 5% of the area they originally occupied on Hawai‘i Island. They disappeared from Hualālai in the late-1800s and were last seen on Mauna Loa in 1950. Palila that occurred in the lowland māmane forests of Kaua‘i and O‘ahu apparently disappeared before western explorers arrived; their presence there is only known from sub-fossil remains.

“Legal History—Palila goes to court”

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 protects palila by providing for the conservation of ecosystems upon which threatened and endangered species of fish, wildlife, and plants depend, and prohibiting unauthorized taking, possession, sale, and transport of endangered species. Below is a summary of the colorful history of palila in court—the first species to ever be named as a plaintiff under the Endangered Species Act.

9th Circuit Judge Samuel King was the first Federal judge of Hawaiian ancestry.

- 1967—Palila were listed as a Federally Protected Species as a result of a continued population decline due to the degradation of the habitat they depend on.

- 1973—Palila were listed as a Federally Endangered Species under the newly rewritten Endangered Species Act of 1973.

- 1978—The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated Critical Habitat on Mauna Kea. Critical habitat is a specific geographic area(s) that is essential for the conservation of a threatened or endangered species and that may require special management and protection.

- 1979—The landmark case, Palila versus the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, federal judge Samuel King ordered the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources to stop maintaining any populations of feral sheep and goats within palila critical habitat on Mauna Kea, and to completely and permanently remove feral sheep and goats from critical habitat.

- 1986—US District Court, Hawai‘i, decides that mouflon sheep in numbers sufficient for sport-hunting purposes are harmful to palila.

- 1987—US District Court, Hawai‘i, orders that state must eradicate mouflon sheep and hybrids within one year and reaffirms previous order to eradicate feral sheep and goats.

- 1998—Defendants and plaintiffs agree to a stipulation and order that DLNR will use its best efforts to minimize migration of ungulates into critical habitat, will continue to include public in eradication by eliminating bag limits and reducing seasonal restrictions and will allow hunting with firearms, guided hunts, and staff hunts, and will conduct semi-annual aerial hunts in which all ungulates seen will be shot.

- 1999—Hunter organizations intervene and with DLNR move to modify the 1987 order; US District Court, Hawai‘i, denies their motion. The request by the defendants to modify the decision was filed on the grounds that introduced predators were the culprits in the decline of the Palila, and that removal of the sheep would increase the risk of fire since the sheep help to reduce fuel loads from flashy grasses. The court affirmed that palila were endangered due to habitat loss from the sheep, that use of the sheep to reduce the fire risk would prevent forest recovery, and denied the motion to modify.

- 2000—Hunter organizations file an appeal of the 1999 decision; US Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, dismisses the appeal on the grounds that the group lacks standing.

- 2009—Earthjustice files motion to enforce the eradication orders of 1979, 1987, and 1998. In its arguments to the court, the State indicated that it would complete the fence work and complete the removal of the sheep in a timely manner.