**IMPORTANT PARK NOTICES**

Monitor weather reports before your park visit.

•

[Hawai\'i] 1/31/26 - Kua Bay at Kekaha Kai State Parks.

•

[O’ahu] 1/28/26 - Mauna Ala, Royal Mausoleum State Monument will be CLOSED February 3, 2026 for palm maintenance.

•

[OʻAHU] 1/5/26 - Kaʻena Point Vehicle Access Permits available now: kaenasups.ehawaii.gov. All applicants must create a NEW account and apply as a new applicant.

•

[ALL ISLANDS] UPDATE – 12/12/25: Camping - Reservations for February 1, 2026 and beyond available at https://explore.ehawaii.gov, please create an account on Explore Outdoor Hawaiʻi to make a camping reservation.

TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE PROTECTS DUNES AT POLIHALE STATE PARK

Posted on May 9, 2025Guardians of the Sands: How Traditional Knowledge Protects Polihale’s Precious Dunes

By Kekai Mar, Park Interpretive Program Specialist, Division of State Parks, Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR)

Imagine the longest white sand beach in Hawaiʻi, with towering dunes over 100 feet high, steep mountains abutting, and a palette of cerulean ocean as far as the eye can see. This expanse of sand dune coastline on the island of Kauaʻi’s western edge is Polihale State Park.

Polihale is more than just a scenic destination. Polihale is known as a leina a ka ʻuhane (leaping place for souls), as it was believed to be the departure point for souls to the spirit world. Many deities and high chiefs are also associated with Polihale, speaking to its sanctity. When we look at the name Polihale, at its core, Pō represents the original night or primordial state of existence, a time before time when the world was in a state of potentiality and possibility, for it is from this darkness that all creation emerged. Poli refers to the bosom or womb, emphasizing the creative and nurturing aspects of this primordial state. With Hale referring to the house, Polihale can be interpreted as the House of Creation/Eternal Darkness.

By exploring the symbolism of these terms, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions of the Hawaiian communities and how they understand and engage with Polihale and the world around them. For generations, Native Hawaiian families have considered this area their home, a place deeply intertwined with their history, culture, and spiritual well-being. Polihale is also a place to harvest marine resources, including iʻa (fish/shellfish), limu (seaweed), and paʻakai (salt). Today, the delicate balance of this precious ecosystem is threatened, and it is vital that we, as park users and stewards of this ‘āina (land), understand how ʻIke Kūpuna (Ancestral Biocultural Knowledge) can guide us in its protection.

Sifting Through The Grit

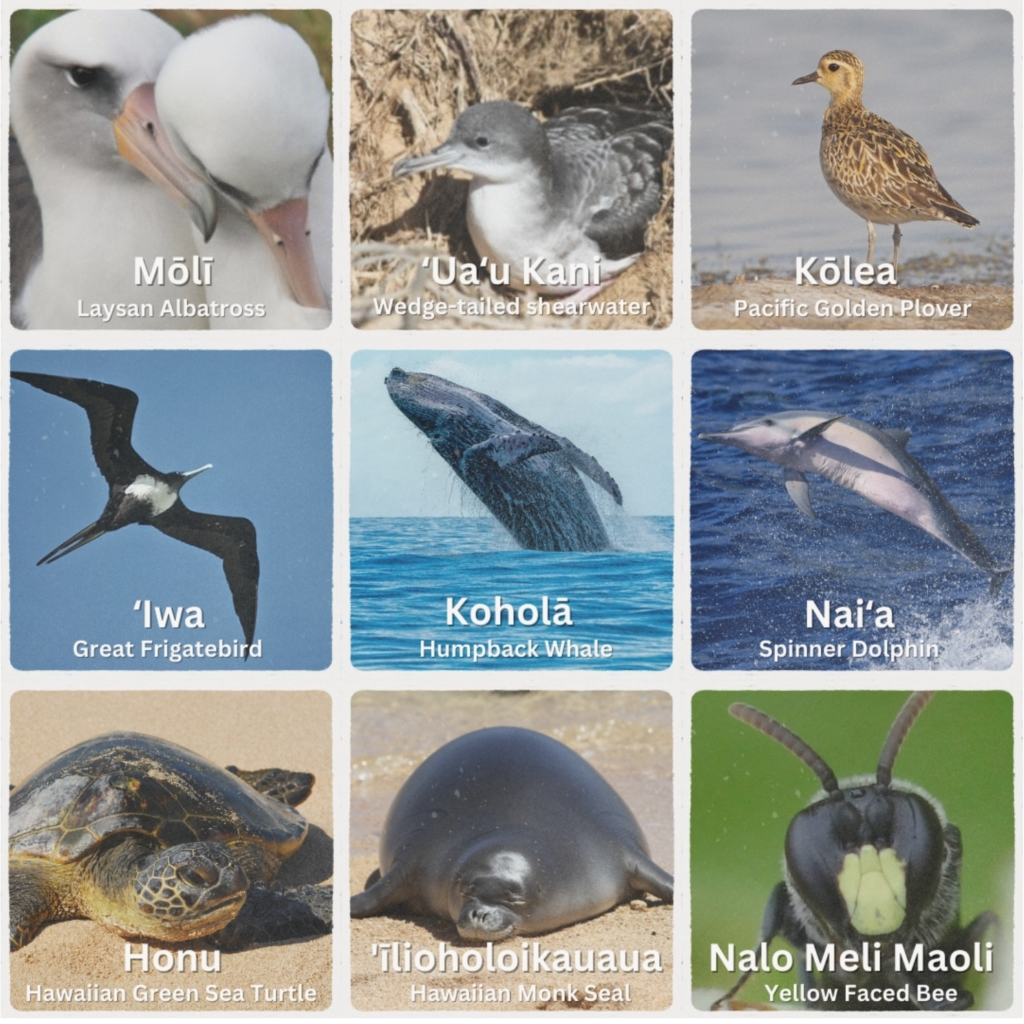

The towering dunes of Polihale, sculpted by wind and waves over centuries, are not simply piles of sand. They are dynamic ecosystems, teeming with life and playing a crucial role in coastal protection. These dunes act as natural barriers, buffering the shoreline from erosion and storm surges. They are also home to unique plant communities, like the pale green and sage-like scented pōhinahina (Vitex rotundifolia) to endemic ʻakoko (Euphorbia celastroides), that stabilize the dunes and provide habitat for endangered native insects like the nalo meli maoli or yellow-faced bee (Hylaeus anthracinus), Hawaii’s main coastal pollinator, as well as the burrowing uaʻu kani (Puffinus pacificus), a protected seabird. Many other flora and fauna, such as the endangered Hawaiian Monk Seal, protected Green Sea Turtles, and other offshore marine life, call this place home.

The very qualities that make Polihale so alluring — its vastness, remoteness, and aesthetic — also contribute to its vulnerability. Unregulated off-roading, in particular, poses a significant threat to the integrity of the dune system. The Hawaiʻi State Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) has noted, driving on the dunes crushes sensitive vegetation, disrupts the natural processes of sand accretion, and compacts the sand, making it more susceptible to erosion. This not only degrades the habitat for native species and undermines the dunes’ ability to protect the coastline, but it also impacts significant cultural resources.

The words of Raylene “Sissy” Kahale, a lineal descendant of Polihale, resonate deeply in this context. As she shared with the DLNR, “Polihale is like our home… This place is so sacred. I don’t think people realize the mana (spiritual energy) that it brings and gives. When you come here, it feels like coming home.” Her poignant statement underscores the intrinsic connection that Native Hawaiians have with this land. This interconnected relationship is built on respect, reciprocity, and a deep understanding of its ecological processes. Hawaiians believed that their survival is dependent upon their interconnectedness with the environment, and the environment depends on Hawaiians because they are kin. Detriment to the environment is detriment to the people.

Look to The Sands of Time

This kinship understanding was passed down through generations. It is known as ʻʻIke Kūpuna, more commonly identified by researchers as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) or Indigenous Knowledge (IK). It encompasses a wealth of cultural information about the natural world, an intersection known as biocultural knowledge.

Kilo (Hawaiian observations) is a foundational traditional practice that may include seasonal changes in plant fruiting and flowering cycles, animal behavior and relationships, migration patterns, names of wind and rain directions, moon phases, and tidal influx linked to agricultural planting and harvesting, and also fishing and hunting seasons. Kilo has continued to be used today in baseline observations and is applied in Polihale resource management.

Another ʻIke Kūpuna involves observing the moon cycles to predict tidal movements, track fish migration, and determine optimal times for planting and harvesting. The moon, personified as the goddess Hina, was considered family and a source of knowledge and wisdom. We can learn from this knowledge by following the moon phases and wet seasons as indicators of what types of plants to install and when to plant, restoring the dunes with appropriate native plants to their natural landscape, while addressing erosion.

Traditional Hawaiian resource management practices, such as the loʻi kalo (flooded taro agricultural system) and loko iʻa (fishpond aquacultural system), were sustainable food systems used to provide sustenance for thousands of people centuries ago and even today. The Mānā plains, surrounding the park, were historically wetlands before water was diverted and land converted to agriculture, changing the natural landscape of Polihale. These wetlands were ideal for such agricultural systems. Currently, agricultural drainage flows through areas of Polihale, providing opportunities for reconstructed wetland restoration and sediment/runoff mitigation.

Nature-based solutions, such as the practice of kilo and Hawaiian resource management practices (loʻi kalo and loko iʻa), are often overlooked as leading strategies in mainstream conservation efforts. They are instead initiated as cultural restoration and preservation efforts, which is incredibly important; however, the ʻIke Kūpuna offers invaluable insight that can be integrated into strategies to protect, restore, and perpetuate the biocultural integrity of Polihale. It all depends on community support, adapting a Hawaiian mindset.

One key aspect of ʻIke Kūpuna that encompasses a holistic watershed perspective, including the integration of sustainable human use, is the concept of the ahupuaʻa, the traditional land division that extends from the mountains to the sea. This holistic approach recognizes the interconnectedness of all ecosystems within a watershed and emphasizes the importance of managing healthy intact resources sustainably across the entire landscape and into the ocean, and even to the lani (heavens). At Polihale, this means understanding how activities in the uplands, such as deforestation or agricultural runoff, can impact the health of the coastal dunes and eventually the offshore reef. Also, considering how camping, recreation, and driving on the beach or dunes in the park can impact these resources and the larger ahupuaʻa, and adapting responsibly. Both park managers and park users.

Lastly, a crucial element of ʻIke Kūpuna is the practice of mālama ‘āina, caring for the land. This principle calls for active stewardship and responsible resource use, ensuring that future generations can continue to benefit from the bounty of the ‘aina. Historically, Native Hawaiians employed a variety of resource management techniques based on mālama ‘āina, such as kapu (restrictions or prohibitions) on harvest or use of space to protect certain areas or resources during specific times of the year, allowing them to regenerate. The ʻʻIke Kūpuna of Kapu could be implemented as symbolic fencing or other boulders used to guide and delineate trails, vehicular borders, or protect restoration sites and culturally significant areas.

Many Grains Make A Dune

ʻIke Kūpuna has been adapted and applied to contemporary conservation efforts at Polihale. At Polihale, the dune system is bioculturally important, so developing a program guided by lineal descendants and built on community-based conservation paves the path for effective collaboration between Hawaiʻi State Parks and community partners.

Recently, Hawaiʻi State Parks and the Division of Forestry and Wildlife of DLNR, the National Tropical Botanical Gardens, and the lineal descendants of Polihale have kilo native plants on-site, noting their position upon the dunes, where the sun and wind are most prevalent, and where moisture is collecting near existing native plant populations. This data became part of the baseline to determine ideal restoration sites, target plants for seed and material sourcing, and vital locations to install appropriate sand rejuvenation and visitor management devices, like fencing and boulders, and interpretive signs.

Using kilo, we planted over 1300 indigenous plants sourced from Polihale last wet season. Pōhinahina, aʻaliʻi, and naupaka were installed near existing native populations, filling in eroded sections of the dunes. Nearly all plants outplanted are thriving, except 3 dozen pōhinahina that were vandalized. We found them hand-pulled and piled on a dune bluff we were trying to fill in. This was disheartening to see, and many resources go into growing these plants.

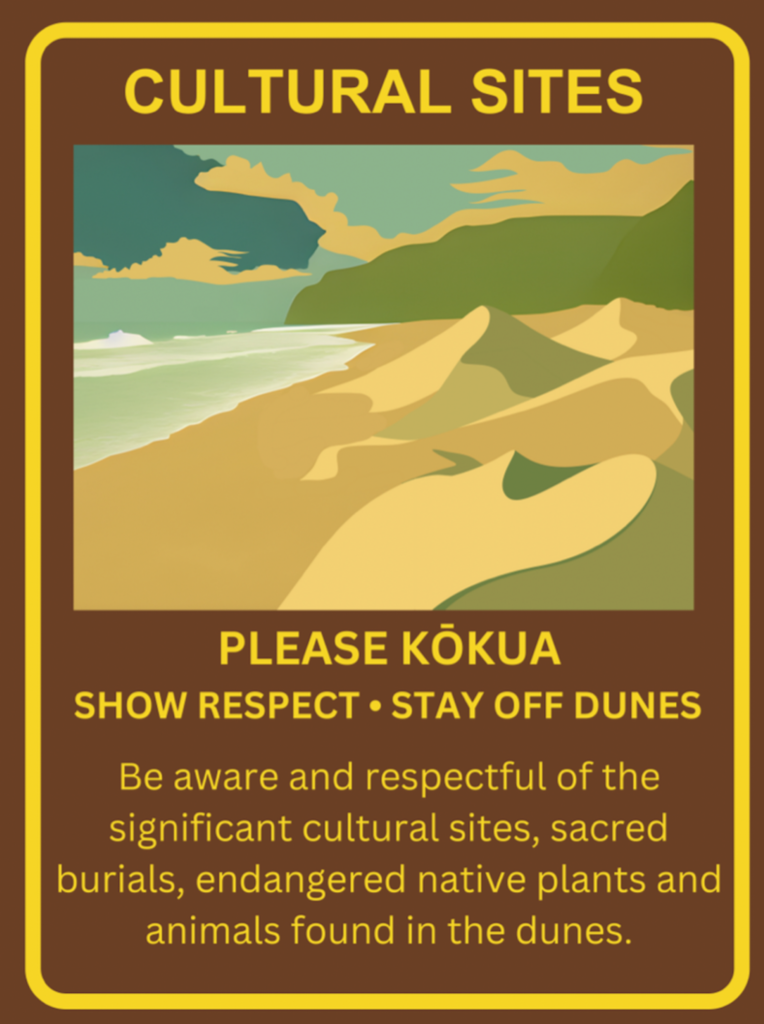

As there is no signage addressing the restoration of Polihale, we designed 3 different interpretive signs, one speaking to Dune Restoration and the other on cultural sites in the dune, both asking for the kōkua (help) of the public to show respect and stay off the dunes. The third sign addresses no vehicles on the dunes and enforces rules. 40 of over 100 signs to educate park users along the 17 miles of dune coast have been installed. They blend into the landscape, yet are visible when approached. They are placed in areas where unsanctioned roads and trails have been established to deter further patronage and dune erosion.

Currently, State Parks has identified designated vehicular access points to the beach, and controlled access can minimize the impact of off-roading on the most sensitive areas; however, there were no resource management devices to prevent driving on the dunes until recently. Before installing the plants, we installed 300 boulders at the base of the dunes where open areas were caused by vehicular driving on vegetation and eroding the dune face. Bordering these access points can prevent vehicles from accessing deeper into the dunes, and paired with interpretive signage, there are opportunities to educate park users on pono (responsible) behavior in the park. Another round of boulders, plants, and signs is slated to continue to border the dunes towards the north end of the park.

Hawaiʻi State Parks has over 30 volunteer groups regularly stewarding some of the most stunning and well-kept parks. As State Parks Assistant Administrator Alan Carpenter mentions, “long-term stewardship agreements with the local Hawaiian community, coupled with visitor limitations, can result in significant improvements in the ecological health of the park, protection of cultural resources, and the quality of the visitor experience.” A similar partnership at Polihale, involving lineal descendants and other stakeholders, is proving instrumental in fostering a sense of shared responsibility for the park’s protection.

Hawaiʻi State Parks has over 30 volunteer groups regularly stewarding some of the most stunning and well-kept parks. As State Parks Assistant Administrator Alan Carpenter mentions, “long-term stewardship agreements with the local Hawaiian community, coupled with visitor limitations, can result in significant improvements in the ecological health of the park, protection of cultural resources, and the quality of the visitor experience.” A similar partnership at Polihale, involving lineal descendants and other stakeholders, is proving instrumental in fostering a sense of shared responsibility for the park’s protection.

It’s not just up to park managers and community leaders. Everyone who visits Polihale has a role to play in its preservation, whether you are a kama’āina (local resident), a lawai’a (fisherman), or a malihini (visitor). We must all embrace a sense of kuleana (responsibility) and treat this place with the respect it deserves. As Officer Armalin Richardson of the DLNR Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement noted, “community involvement has been key to improving behavior at Polihale.”

When people understand the cultural and ecological importance of the place, they are more likely to treat it with respect. The most important thing you can do is to stay on designated roads and trails. Respect the signs and barriers that are in place to protect sensitive areas. Support local organizations that are working to restore and conserve the dunes through volunteerism. Share your knowledge and passion for Polihale with others, encouraging them to be responsible stewards of this special place.

Let us honor the wisdom of our kūpuna (elders) and act as responsible park users, or better yet, guardians of this precious ‘āina (land). It’s up to us to shift the current narrative of disrespect and carelessness towards one of reverence and conscious stewardship. We must come together to ensure that Polihale remains not an “endangered species”, as lineal descendant Sissy so eloquently stated, but a thriving testament to the power of cultural connection and community collaboration in conservation.

Source

Hawaiʻi State Department of Land and Natural Resources. Malama Polihale Lineal Descendants. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/499830965?share=copy

Hawaiʻi Division of State Parks. https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dsp/parks/kauai/polihale-state-park/