Coral Impacts

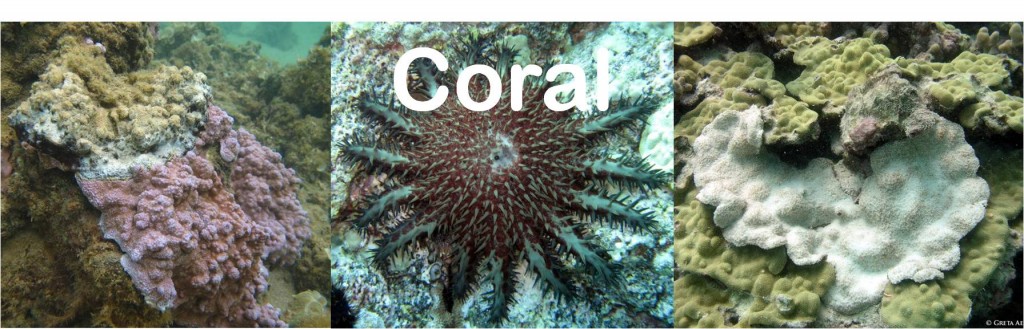

What is coral disease?

What is coral disease?

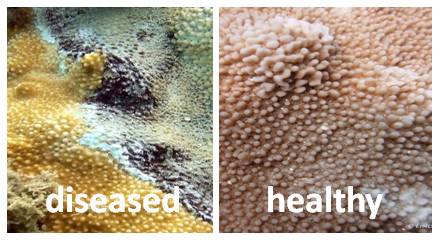

Corals are slowly-growing living animals that co-exist with specialized algae in their tissue that provide essential nutrients, called zooxanthellae. Corals are susceptible to disease, as all animals are, and therefore can get sick and die. Diseases can and do kill coral reefs. In the Caribbean, over 80% of reef corals have been lost due to disease. In Hawaii, there have been a few isolated events of coral disease but with climate change impacts we are likely to see outbreaks more often.

What causes coral disease?

Coral disease can be the result of infectious or non-infectious agents. In many cases, pathogens already exist in the wild, and as corals become stressed from human and/or natural disturbances, their immune system is weakened and they are therefore more susceptible to disease. Exposure to stressors can make corals more vulnerable to disease; the stressors include physical damage, land-based pollution, and resource extraction, as well as non-anthropogenic disturbances including temperature stress and ocean acidification.

What is DLNR doing?

Coral diseases are an emerging issue. Relatively little is known about coral disease and ways to manage diseased reefs. Research is currently being conducted in Hawaii and around the world to fill knowledge gaps including how diseases are transmitted, how diseases harm coral colonies and cells, what drives the presence of diseases on certain reefs, and more. These data will provide essential information to more effective identify management options.

Healthy corals usually appear tan, brown or green from the presence of the zooxanthellae (or algae) within their tissues. Some types of corals have additional pigments so may appear more blue or purple. Coral bleaching is a stress response. The term “bleaching’ describes the loss of color that results when zooxanthellae are expelled from the coral polyps or when chlorophyll within the algae are degraded. When the zooxanthellae leave the coral, the white of the coral skeleton is then clearly visible through the transparent coral tissue, making the coral appear bright white or ‘bleached’. Some corals, such as our lobe coral, have additional pigments in their tissue, so when they ‘bleach’ they may turn a pastel shade of yellow, blue or pink rather than bright white.

What causes coral bleaching?

Coral bleaching can be caused by a wide range of environmental stressors such as pollution, increased sedimentation, changes in salinity, low oxygen, or disease. However, the primary cause of mass coral bleaching is increased sea temperatures. Corals are very sensitive animals so water temperatures need only increase 1-2 degrees Celsius above normal levels for bleaching to occur. If the stressful conditions return to normal rather quickly, the corals can regain or regrow their zooxanthellae and survive. If the stressors are prolonged, the corals are more likely to die because they lack an important energy source. Not all corals are equally susceptible to bleaching. Fast-growing branching and plate corals are often the first to bleach and are more likely to die from bleaching. Slower growing massive corals usually take longer to bleach and tend to be able to survive for longer in the bleached state.

What is DLNR doing?

Worldwide, localized coral bleaching has been recorded for over 100 years. In the last 20 years, mass coral bleaching events have occurred including. When a mass bleaching event occurs, recovery is very slow and dependent on new, young corals settling and growing on the reef. Re-growth of reefs that have been severely damaged by bleaching may take decades. Recovery is especially difficult for reefs in locations suffering from other stresses such as pollution, overfishing or other chronic pressures. Coral bleaching is predicted to occur much more frequently due to higher sea temperatures associated with global climate change. DLNR is working with partners to monitor sea temperatures, assess bleaching events, and focus management actions on resilience, or ability to resist and recover from bleaching events.

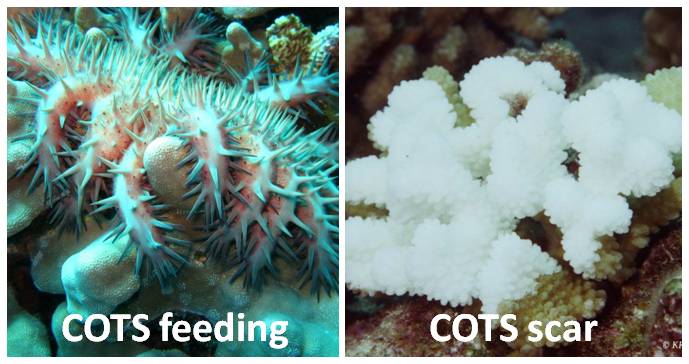

What are Crown-Of-Thorns-Starfish (COTS)?

Crown-of-Thorns-Starfish (COTS) are unusually large sea stars that can grow to almost 3 feet in diameter. They have up to 19 arms, with the entire upper surface covered with sharp venomous spines and can move up to 65 feet per hour. They are a threat because COTS have a voracious appetite for live coral and can take over coral reefs quickly due to their ability to spawn millions of eggs a year. COTS feed on coral by pulling its stomach out of its mouth with its tube feet and placing it on the coral. Digestive enzymes kill the live coral and the stomach absorbs the tissue, leaving the white calcium carbonate skeleton.

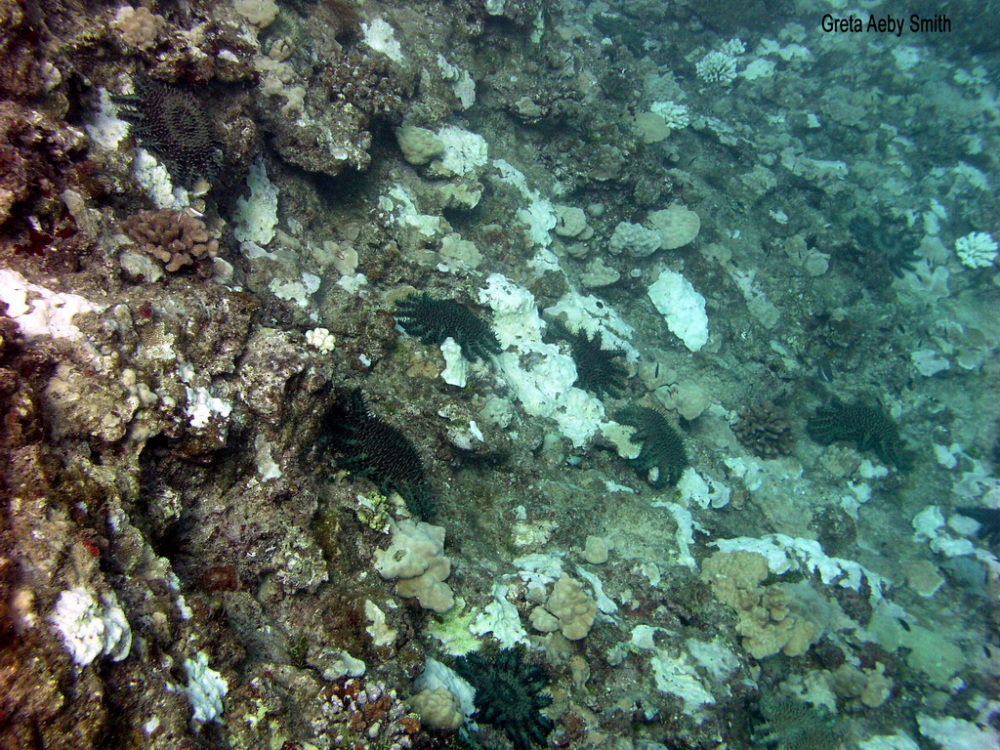

COTS in Hawai`i

In Hawai`i, COTS primarily feed on rice, lace, and cauliflower corals. Healthy reef systems can support small populations of COTS for many years with only a small reduction in coral cover. But when a COTS outbreak occurs, there can be many animals per square foot, and it can take many years for the reef to recover. Natural population controls include the high mortality of the larvae, high predation of juvenile COTS, and feeding on adults by Triton’s trumpets, Harlequin shrimp, and stripebelly puffers.

What causes COTS outbreaks?

- Natural changes in the population. Natural fluctuations in temperature, salinity or availability of food could all contribute to improving the survival of COTS larvae.

- Removal of predators. Loss of natural predators that feed on the juvenile and adult COTS an be costly. Predation on juveniles decreases the number of COTS that reach reproductive maturity. Increased nutrients lead to increased planktonic food, improving larvae survival. Outbreaks sometimes occur in areas with high levels of nutrients, which generally accumulate from terrestrial runoff.

What is DLNR doing?

There are few options to manage COTS outbreaks and it is impossible to eradicate COTS from reefs where they are in outbreak densities. However, with sufficient effort, small areas can be protected. Because sea stars can quickly move from one area to another, control of a specific area must be an ongoing effort and may be required on a daily basis. Thus, early detection and reporting of any unusual numbers of COTS can help reef managers minimize the impact of a COTS outbreak. Online report forms for the EOR Network can be found at www.eorhawaii.org/make-a-report.