Monitoring

Marine Monitoring Program

The current DAR Marine Monitoring Program employs numerous different methodologies developed by DAR scientists in collaboration with NOAA, USGS and UH. Specific methods are used at study sites depending on the resource management concerns that DAR is looking to address, and include surveys of abundance of resource and herbivorous fish, smaller cryptic fish and recruits, urchins and larger mobile invertebrates, benthic habitat cover, coral health and biological diversity.

MONITORING OBJECTIVES

Routine marine monitoring has been a component of the Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) (formerly the Department of Fish and Game) for over 50 years. Early efforts concentrated on using in-water visual assessments to measure resource fish stocks and changes to those stocks within marine protected areas and at artificial reef sites. For the past 15 – 20 years, efforts have been made to improve upon research methods, increase the frequency of surveys, expand the number of areas covered by assessments, and study changes associated with new management initiatives. As a result, today’s marine monitoring efforts are based on multi-faceted annual assessments of the coral reef ecosystem across a range of management zones. The current DAR marine monitoring program employs numerous different methodologies developed by DAR scientists in collaboration with NOAA, USGS, and UH. Specific methods are used at study sites depending on the resource management concerns that DAR is looking to address, and include surveys of abundance of resource and herbivorous fish, smaller cryptic fish and recruits, urchins and larger mobile invertebrates, benthic habitat cover, coral health and biological diversity. Advances in technology have also allowed for broader use of GPS and digital photography and allowed monitoring information to be analyzed and displayed in a GIS format.

Herbivore Fisheries Management Area

Monitoring of coral reef habitats on Maui began as early as 1993. When compared with the results of current reef monitoring, these long-term data sets have allowed for the identification and quantification of trends at nearly all monitored reefs. Many sites experienced a complete collapse of the coral community, as live coral cover dropped dramatically and reefs became dominated by invasive algae. The results of these monitoring efforts have been instrumental in helping the department identify a specific location were management action may help reverse the decline in reef habitat before it is too late.

At the Kahekili reef monitoring sites in north Kā’anapali, Maui, coral cover was found to have declined from 55% in 1994 to 33% in 2006. This information, coupled with fish surveys suggesting reduced herbivorous fish abundance, helped guide the establishment of the Kahekili Herbivore Fisheries Management Area (KHFMA). The rules at the KHFMA prevent take of critical grazing fish and sea urchins and became effective in July 2009. The implementation of these rules was the first time in Hawai’i that fisheries management was employed specifically to help protect coral reef habitat. The creation of the KHFMA has also been critical in helping to increase public awareness of the many factors affecting our coral reefs and helping to drive land management policies towards reducing land-based pollution. Ongoing habitat and fish monitoring projects continue within this area in order to assess the effectiveness of the management efforts, and to guide future adaptive management.

Since the KHFMA was created in 2009, there have been numerous documented benefits. Parrotfish biomass has increased to more than four times its earlier level (+331%). In 2018, biomass of parrotfishes larger than 10 inches in total length was more than 10 times the 2008 level. Surgeonfish biomass has also increased, to a little under twice what it was in 2008 (+ 71%). The reef itself has also changed – there is reduced cover of problem seaweeds (‘macroalgae’, and dense turf), and there has been about a 4-fold increase in crustose coralline algae (CCA). Coral cover, which had been declining at the time of the KHFMA establishment, leveled off and appeared to be increasing through 2013 and 2014. In 2015, Maui was hit by a major bleaching event, which resulted in a small decline in coral cover. Maui was not the worst affected island, but still ~20% of all Maui coral died during and following that event. Maintaining healthy herbivore communities is one way we can help corals to rebound from bleaching in the future.

Assessment of Lay Net Regulations

In 2007, lay net fishing bans expanded to include the entirety of Maui, and three regions on O‘ahu:

- Portlock Point to Keahi Point (west of Pearl Harbor channel)

- Kailua Bay (Mokapu Peninsula to Wailea Point (northern boundary for Bellows AFB)

- Kāne‘ohe Bay (a portion of the Bay; landward boundaries would be the main ship/sampan channels and landward of Ahu’olaka)

In response, the Fish and Habitat Monitoring Program on Maui and O‘ahu set out to study ecological trends in these areas. As the primary monitoring sites and methodologies employed on Maui and O‘ahu were developed prior to the implementation of the expanded lay net restrictions, additional sites and survey methods were developed to address this management initiative. The program also added components to standard protocols that place greater emphasis on herbivorous fish and urchins and to detect changes in dominant coral and algal species.

On Maui and O’ahu, teams are monitoring areas where lay net fishing was prohibited and comparing results to control sites where this fishing method is still permitted. In Kāne’ohe Bay, sixteen transect sites were established in the bay to cover fringing, barrier and patch reef habitats both inside and outside of the no lay netting zone. Sites were also selected in areas where the DAR Aquatic Invasive Species team is using urchins to control invasive algae, and in the no fishing zone around Moku o Lo‘e (Coconut Island). Research protocols were customized to the unique habitat structure in Kāne’ohe Bay, but include surveys of resource and herbivorous fish abundance and detailed benthic surveys to study trends in algal and coral cover. Additional survey sites have also been established to study ecological trends in shallow fringing reef habitats in areas such as Mamala, Hanauma, Waimānalo and Kailua Bays on O’ahu. On Maui, seven sights were added to the original monitoring locations. The Maui sites were selected and characterized based on the extent of past lay net fishing. Overall, these broadscale fish and habitat monitoring efforts should help evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the laynet fishing regulations.

West Hawaii Aquarium Project

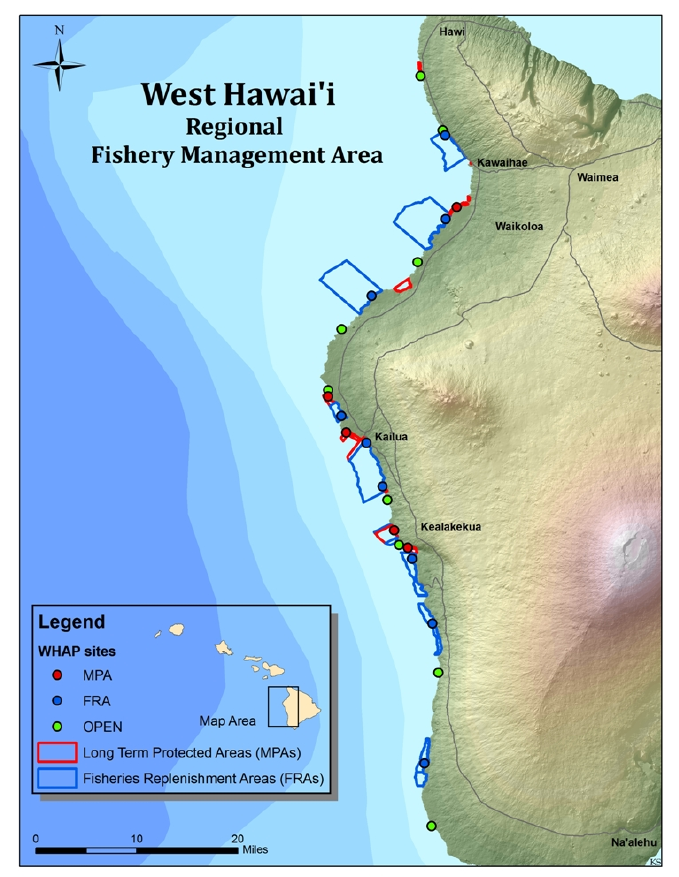

In 1998, Legislative Act 306 resulted in the establishment of the West Hawai’i Regional Fishery Management Area. Resulting management actions included the designation of 9 Fish Replenishment Areas (FRAs) where aquarium collecting became prohibited. Combined with existing marine reserves, this action set up a network of marine managed areas making aquarium collection off-limits along 35.2% of the West Hawai’i coastline. In order to study the impacts of the FRA network, and of continuing aquarium fishing in areas remaining open to collectors, DAR and partner researchers from UH Hilo and Washington State University Vancouver initiated the West Hawai’i Aquarium Project (WHAP). Twenty-three permanent fish monitoring sites were established within representative locations at previously protected areas (MPAs), newly established FRAs, and areas allowing for continued aquarium collection (Open Areas). Since their establishment in 1999, these sites have been routinely surveyed 4 – 6 times per year.

Since the establishment of the FRAs over 20 years ago, the size and value of the West Hawai’i aquarium fishery has undergone substantial and sustained expansion. Total catch and market value have increased by 29% and 143% respectively since FY 2000. Approximately 26% of both the total number of aquarium fish caught in the State and value of the catch came from West Hawai′i prior to the closure of the fishery in 2018. In the 20 years after the closure, the population of Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens), which accounted for 81.6% of total take, has increased 165% in the FRAs, 74% in existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and 101% in the Open Areas where all aquarium fishing effort has been directed. The FRAs have also been very successful in increasing Kole (Ctenochaetus strigosus) populations. This species is the second most collected species in the aquarium fishery, representing 9.5% of the 3 total catch. In the 20 years after FRA closures, Kole populations have increased 85% in the FRAs, 120% in the MPAs and 97% in the Open Areas. The overall mean abundance of the combined top 3-10 collected aquarium species has increased in all management areas since the FRAs were established. These monitoring results have been instrumental in documenting the success of the overall FRA management approach, and importantly, they are helping to guide the West Hawai’i Fishery Council (WHFC) and DAR as they adaptively manage this important fishery for future sustainability.

Since the establishment of the FRAs over 20 years ago, the size and value of the West Hawai’i aquarium fishery has undergone substantial and sustained expansion. Total catch and market value have increased by 29% and 143% respectively since FY 2000. Approximately 26% of both the total number of aquarium fish caught in the State and value of the catch came from West Hawai′i prior to the closure of the fishery in 2018. In the 20 years after the closure, the population of Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens), which accounted for 81.6% of total take, has increased 165% in the FRAs, 74% in existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and 101% in the Open Areas where all aquarium fishing effort has been directed. The FRAs have also been very successful in increasing Kole (Ctenochaetus strigosus) populations. This species is the second most collected species in the aquarium fishery, representing 9.5% of the 3 total catch. In the 20 years after FRA closures, Kole populations have increased 85% in the FRAs, 120% in the MPAs and 97% in the Open Areas. The overall mean abundance of the combined top 3-10 collected aquarium species has increased in all management areas since the FRAs were established. These monitoring results have been instrumental in documenting the success of the overall FRA management approach, and importantly, they are helping to guide the West Hawai’i Fishery Council (WHFC) and DAR as they adaptively manage this important fishery for future sustainability.