8/7/23 – How is stream ecology connected to coastal fishing?

Contributed by: Kim Peyton, Heather Ylitalo-Ward, Neal Hazama, Tim Leichliter, Troy Shimoda, Troy Sakihara, Jody Kimmel-Brown, Tim Shindo

On a recent estuary survey at Waimea River on Kauaʻi, the DAR Estuary Team was able to document an amazing migration of tens of thousands of hinana (post-larvae of ‘o‘opu wai) as they entered the stream mouth estuary on their way to freshwater habitat. Luck that day continued with a coinciding feeding frenzy by juvenile (pua) āholehole (Kuhlia xenura).

However, Waimea is no stranger to this type of event, as described in an ‘ōlelo no‘eau (Hawaiian proverb) —Ka i‘a ho‘opā ‘ili kanaka o Waimea, The fish of Waimea that touch the skins of people. When it was the season for hinana, the spawn of ‘o‘opu, at Waimea, Kaua‘i, they were so numerous that one couldn’t go into the water without rubbing against them (Puku‘i 1983). These experiences on the Westside of Kauaʻi supported lessons shared by kūpuna, as Waimea River revealed how our streams, estuaries, and marine ecosystems are all interconnected. Streams feed estuaries and estuaries are the nursery grounds for many marine species.

A successful ‘o‘opu nopili adult settled in Honomanū Stream on Maui. ‘O‘opu nopili are usually found in the greatest numbers above the first significant waterfall.

With an early morning low tide, freshwater flow to the ocean was strong because the Pacific wasn’t holding Waimea River back. Along the very edges of the river shoreline, where the shallowness of the water slows down flow velocity, hinana were swimming upstream. Impressively determined swimmers at about 5/8 inches long, we watched as hinana piled up behind boulders inside the river mouth. Here these newly arrived fish waited for the tide to turn, before setting off again on the last segment of their journey to adult habitat. A journey that, depending on the species of ‘o‘opu, can include climbing waterfalls.

Thousands of hinana, seen here as a dark brown curve in the center of the photo, are lining up in the lee of a boulder waiting for the tide to slacken. When slack tide started, we checked this area again and confirmed that the hinana had moved upstream.

To identify and measure fish that benefit from estuaries, one monitoring method the DAR Estuary Team developed relies on cast nets. Some casts hauled in hinana, allowing us to photograph and determine—thanks to Skippy Hau’s expertise—that this freshwater species recruiting to Waimea River was ‘o‘opu nopili (Sicyopterus stimpsoni). Although their bodies are mostly clear as planktonic larvae floating in ocean currents, ‘o‘opu nopili become pigmented with a distinct striped pattern upon entering estuaries. ‘O‘opu nopili typically climb waterfalls to reach their preferred adult habitat.

‘O’opu nopili hinana from Waimea River, Kauaʻi. Note the distinct banding pattern of these post-larvae.

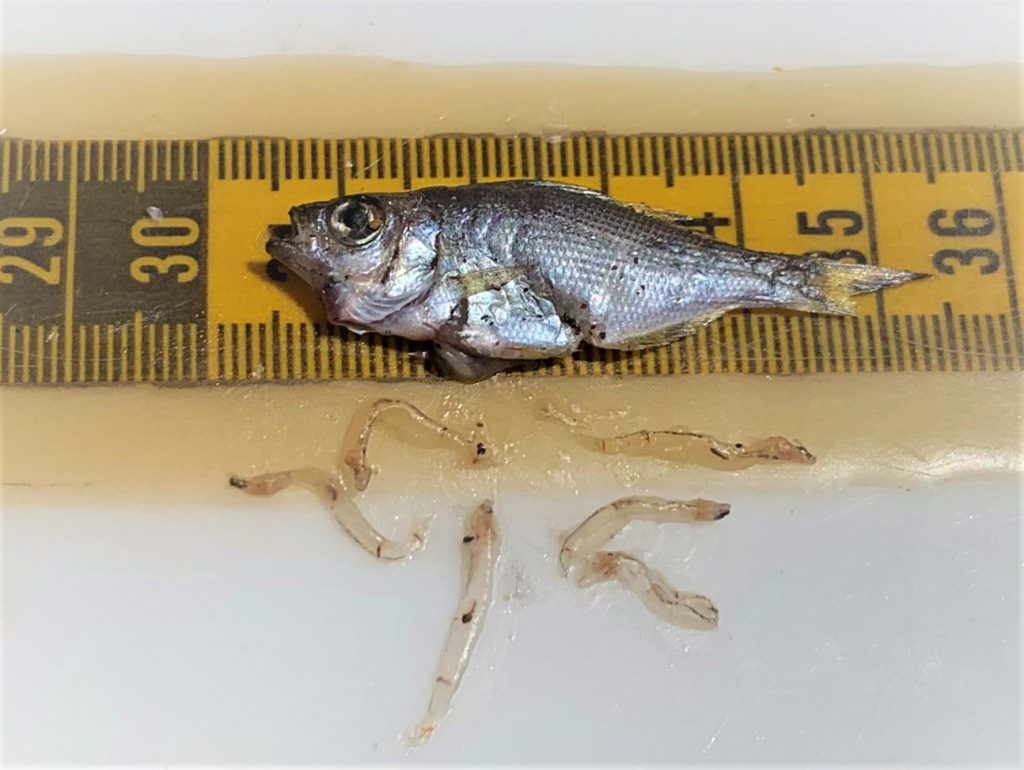

Juvenile āholehole, 2 to 3 inches long, were also caught in the cast net. Remarkably, all these pua had overstuffed midsections. Two āholehole were dissected to determine if their bulging stomachs were from gorging on migrating hinana. One āholehole had a stomach full of six hinana, a remarkable amount of food for such a small fish. To our surprise, the other āholehole had eaten at least 14 juvenile ‘ōpae. Examining the stomach contents of the second āholehole yielded information that would have gone undetected otherwise. Migrating juvenile ‘ōpae kalaʻole (Atyoida bisulcata) are challenging to see because their bodies are still mostly clear as they transit through estuaries. We recorded two stream species recruiting to Waimea River while monitoring, and āholehole pua took advantage of this bounty by preying on hinana and ‘ōpae during their obligatory movement between marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Āholehole pua with a full belly.

Not all the āholehole pua gorged on hinana, some preyed on migrating juvenile ‘ōpae kalaʻole. This fish consumed at least 14 ‘ōpae kalaʻole in the estuary.

Even though this āholehole pua was only 2-3 inches long it had consumed at least six hinana. Notably, āholehole pua swallow hinana whole.

These events in Waimea River captured a critical ecological balance between streams and estuaries. Hawaiian streams are mostly shallow, narrow waterways that lack adequate space and food resources to support tens of thousands of individuals from each of our nine stream species. Only the strongest and luckiest juveniles complete a journey to their adult habitat in the upper stream reaches. The majority serve another essential ecological role as food for rapidly growing pua, such as āholehole. Productive streams offer reliable sources of food in estuaries. For this reason, healthy streams and estuaries that attract tens of thousands of recruiting hinana and ‘ōpae play significant roles in sustaining coastal resources.

Mahalo to Klayton Kubo for his input to the DAR Estuary Team. As a result, Waimea River on Kauaʻi was added to our monitoring rotation of 13 estuaries statewide. On Kauaʻi the DAR Estuary Team monitors the estuaries at the mouths of Waimea River, Hanalei River, and Anahola River four times per year. DAR Kauaʻi staff join in this effort, and we all learn quite a lot from these shared experiences.

This work is funded by US Fish and Wildlife Service Sportfish Restoration program and the State of Hawai’i.