Sharks and Rays

Sharks and rays: Facts about three important species in Hawaiian waters

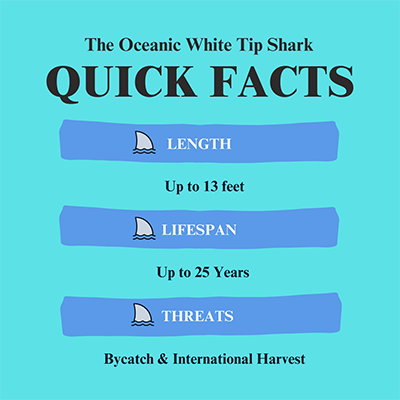

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Hawaiian name: ka manō

Scientific name: Carcharhinus longimanus

Description and Natural History

Description and Natural History

The oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) is often found offshore in the open waters of all tropical oceans worldwide. This is the only oceanic shark of its genus. They can easily be confused with silky sharks (C. falciformis), coastal blacktip sharks (C. limbatis), and Galapagos sharks (C. galapagensis). A fundamental way to identify oceanic whitetips is their unique white-mottled markings at the tips of their dorsal (top), pectoral (side), and caudal (tail) fins.

Status and Protection

In 2018, the oceanic whitetip was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The International Union for Conservation Nature (IUCN) lists them globally as critically endangered, meaning they face an extremely high risk of extinction [1]. It is known that their populations have dramatically declined due to bycatch in commercial fisheries combined with the rise in demand for shark fins internationally [2]. However, there is not much research currently available about the population dynamics of these sharks.

In 1996, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) began requesting shark data that included the oceanic whitetip shark. These international reports have included data from countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Spain, St. Lucia, the United States, and even Japanese long-line fleets. The overall evaluation of their conservation is limited by the standardized catch and abundance data and the resulting absence of stock assessment studies. As more fisheries report to ICCAT, the prospects for assessing the impact on oceanic whitetip stocks will improve.

DAR is currently collaborating with the Hawai‘i Shark Tagger team to help with photo identification of the oceanic whitetip sharks to better understand their population size and structure around Hawaiʻi [2]. The Shark Tagger team uses photographic identification methods using fin markings, coloration, and scarring to establish baseline information on oceanic whitetip shark demographics in the Hawaiʻi region. Please submit your photos to the Shark Tagger website.

Diet and Habitat

Oceanic whitetip sharks are a top predator species but are opportunistic feeders. This means they feed on various prey and often eat what’s available, they have also been observed eating the scraps of Pilot Whale catches. Their typical diet consists of bony fish and cephalopods, such as squid, cuttlefish, and octopus. They have also been seen foraging on large pelagic game fish, like tuna, and prey on sea birds, sharks and rays, marine mammals, and marine debris [2].

The oceanic whitetip shark is found worldwide in tropical and subtropical waters [9]. They are found from surface level to at least 200 meters in depth and can be found in pelagic (open ocean) waters. However, catch rates suggest that oceanic whitetips are found in shallow waters more commonly than other pelagic sharks. Little is known about the overall migrations and movements of these species.

Reproduction

Reproduction

Oceanic whitetip sharks live up to 25 years. They give birth every other year to a litter of pups ranging from one to 14. Their gestation period, or when the female is pregnant, is 10 to 12 months, and when they do give birth, it is live birth. The females take about four to five years to reach sexual maturity [4].

There are few studies on the reproduction of oceanic whitetip sharks. A study found that there is no specific parturition period, when the females give birth, in the North Pacific. There were pregnant individuals observed almost every month of the year [4].

Threats – Bycatch and International Harvest

Oceanic whitetip sharks are highly susceptible to being caught as bycatch in many Hawai‘i fisheries especially longline, purse seine, and gillnet [2]. Oceanic whitetips are also targeted internationally and illegally for several different products. Their meat and skin are used for human consumption, their hides can be used for leather, and their liver oil can provide Vitamin A. Their fins are the most highly valued in the international trade for shark products. Many consider shark fin soup a delicacy, prepared by boiling the fin cartilage until it breaks into long stringy strands that look like noodles. It is illegal to possess, sell, offer for sale, trade, or distribute shark fins anywhere in Hawai‘i (HAR 188-40.7). Anyone who sees any of these activities is asked to call the DLNR hotline at 643-DLNR (643-3567) or to report it via the free DLNRTip app.

These populations have been declining due to these issues but, because the oceanic whitetip species is highly migratory, it is hard to interpret trends, overall impacts, and remaining numbers for these sharks.

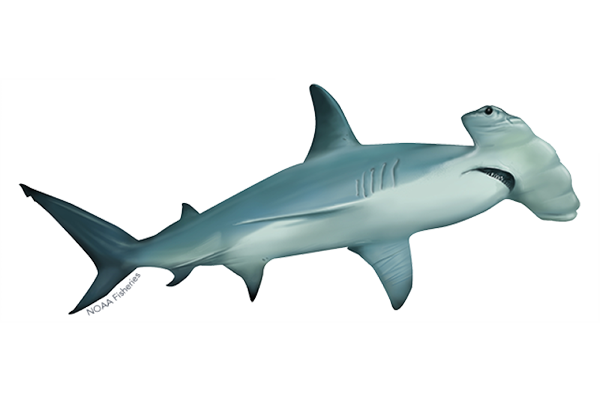

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark

Hawaiian name: ka manō kihikihi

Scientific name: Sphyrna lewini

Description and Natural History

Description and Natural History

The hammerhead shark is one of our oceans’ most unique and alien-looking shark species. The scalloped hammerheads are recognized by a flattened hammer-like head with four “scallops,” or lobes, between their eyes on the leading edge of the head. Their bodies are gray with lighter underbellies, known as countershading, a widespread trait with offshore species used for camouflage. Adult scalloped hammerheads live offshore and come into shallower areas to pup. These sharks have been recorded as deep as 900 feet [5].

The scalloped hammerhead’s uniquely flattened head serves several functions; it could enhance the sharks’ sense of electroreception (the biological ability to perceive natural electrical stimuli), provide additional maneuverability in the water, and aid their sense of smell [6].

Status and Protection

The global population of scalloped hammerheads is listed as critically endangered under the IUCN. The scalloped hammerhead has many Distinct Population Segments (DPS), two of them being the Eastern Atlantic and the Eastern Pacific. Both populations are listed as endangered under the ESA [7]. Another two scalloped hammerhead DPS are the Central & Southwest Atlantic and the Indo-West Pacific populations. These populations are listed as threatened under the ESA. Hawai‘i’s scalloped hammerhead population is part of the Central Pacific DPS and is not listed under the ESA.

Diet and Habitat

Juvenile scalloped hammerhead sharks primarily feed on bony fish and squid, while adult diets range from bony fish, squid, and other sharks and rays [5]. Hammerheads are often seen alone; however, they are also often seen in larger schools. The scalloped hammerhead shark is considered a shy and docile species. They are often not likely to approach divers or swimmers.

Reproduction

Reproduction

Like most species of sharks, the adult scalloped hammerheads live offshore and come into shallower waters of protected bays in Hawai’i to pup. Adult scalloped hammerheads have been recorded inshore between April and October for birthing and breeding. This shark species is viviparous, meaning their eggs hatch inside their body, where the pups feed off the yolk sac placenta until they are born. Common pupping sites in Hawai’i are Hilo Bay, Kane’ohe Bay, and Waimea Bay [5]. The gestation period is 11-12 months and litter size ranges from 15-31 pups. The pups spend three to four months in the bay and then return to deeper waters. The total number of pups passing through Kane’ohe Bay has been recorded to be as high as 10,000 per year. Adult scalloped hammerheads can reach up to lengths of 13 feet and average six to eight feet in the Hawaiian Islands.

Threats

Scalloped hammerhead sharks are fished commercially for food and their fins. They are mainly threatened by overutilization by industrial/commercial and artisanal fisheries, habitat degradation, minimal fishing regulations, and their vulnerability to fishing pressure due to the scalloped hammerheads’ schooling behavior [7]. Shoreline degradation and habitat loss may also be a factor in their decline because scalloped hammerheads are born in shallow coastal waters.

Identification

See how to identify four species of brown sharks in Hawai‘i.

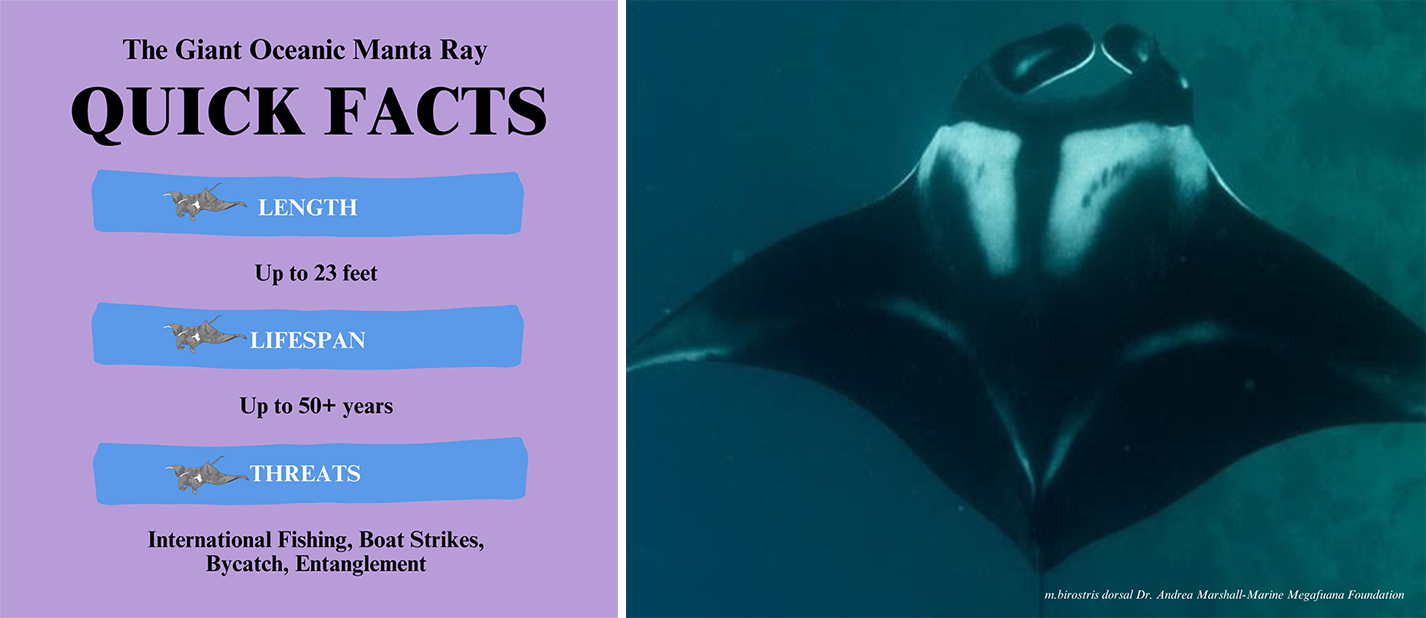

Giant Oceanic Manta Ray

Hawaiian name: ka hāhālua

Scientific name: Mobula birostris

Description and Natural History

Giant oceanic manta rays (Mobula birostris) [8] are cold-blooded fish with flat diamond-shaped bodies. The oceanic manta is the world’s largest ray, with a wingspan of up to 26 feet across and weighing up to 5,300 pounds [9]. They can live over 45 years, based on photo-identification records. They are often solitary most of their lives, but aggregate around food resources, cleaning stations, or in mating trains. They have the largest brain-to-body mass of any fish, making them very intelligent. They each have a spot pattern on their ventral (under) side that makes each one unique, like a human’s fingerprint, allowing them to be monitored over time using photo identification. In 2009, Dr. Andrea Marshall and her team described the visually distinct differences between oceanic mantas and reef mantas [10]. In 2011, Dr. Tom Kashiwagi and his colleagues analyzed and confirmed the genetic difference between the two species [11].

Status and Protection

In 2018, the oceanic manta ray was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act [12]. Globally, their populations have declined primarily due to bycatch in commercial fisheries combined with the rise in demand for gill rakers internationally [9]. Due to its pelagic nature, the oceanic manta ray can be difficult to study, so there is still much to learn about their ecology and home range.

Diet and Habitat

These large, filter-feeding elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays) are thought to spend most of their time in deep water but are occasionally seen coming close to shore. They primarily feed on plankton by creating a funnel with their cephalic fins in an “O” shape and then opening their mouths. This allows them to push large volumes of water, through their mouth and over their gill rakers, which filter and divert the plankton into their stomach. They are commonly seen barrel rolling and creating feeding chains to maximize feeding efficiency [9].

What is plankton?

What is plankton?

Plankton is any organism that drifts in the ocean currents. There are two types of plankton, phytoplankton (plankton that photosynthesize) and zooplankton (plankton that eat smaller plankton). Phytoplankton are at the base of the oceanic food chain and some zooplankton engage in one of the earth’s largest migrations. Billions of these tiny creatures swim vertically as a mass movement from the sea’s depths towards the ocean’s surface. They swim upward as far as 1,500 feet each evening and then return to the dark depths in the morning to avoid predation.

Reproduction

Although oceanic mantas are suspected to live beyond 45 years, very little is known about their life history. It was found that in their close cousins, the reef-associating manta rays, gestation (how long the female is pregnant) takes 12-13 months [13]. They have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (sharks, skates, and rays), typically giving birth to a single pup every couple years. Reef-associating manta rays have been born in captivity measuring just under 6 feet wide [13]. A wild birth has never been observed; please record this event if you see it.

Threats

The oceanic manta rays are often targeted by global fisheries for their highly prized gill rakers or accidentally caught as bycatch. Due to their large bodies, they are highly susceptible to entanglement, often associated with the purse-seine and artisanal gillnet fisheries and recreational fisheries in nearshore waters [9]. The international fishing trade catches oceanic mantas strictly for their gill rakers, then sells them illegally for “healing tinctures”. They can also be injured from boat strikes while feeding or traveling just below the surface. They can also become entangled in nets or other fishing gear, accidentally ingest microplastics, or lose prey resources due to ocean acidification.

The only natural predators to oceanic manta rays are presumed to be large sharks and killer whales based on photo evidence of bites.

If you see an oceanic manta ray, please do not disturb their natural behavior

by touching or chasing them.

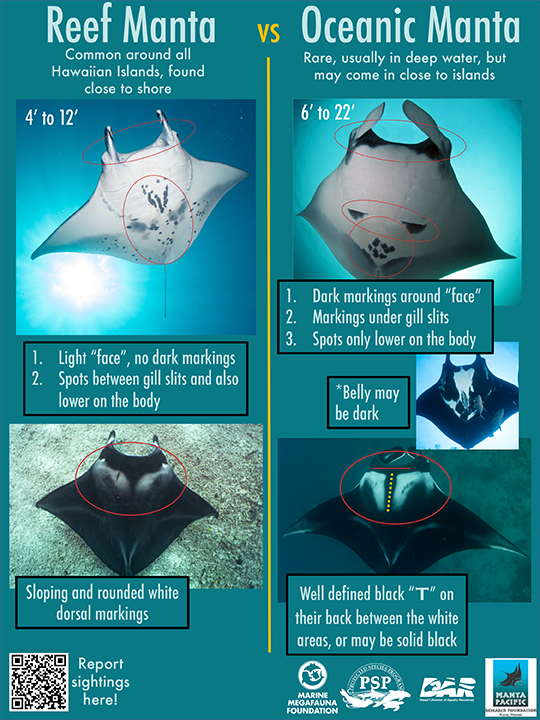

How to spot key differences between the oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris) and the reef manta (Mobula alfredi) (hāhālua):

Oceanic manta rays: The dorsal surface (topside) of the oceanic manta ray is dark with two white triangular markings and marked without a gradient. The line of separation between these two white areas forms a “T.” Their ventral (underside) has a white coloration with black spots clustered below their gills (but not between the gills). The edges of their bodies tend to have dark margins including their cephalic fins and around their mouth. See image below.

Reef manta rays: The reef manta ray has a dark dorsal surface also with two lighter areas on top of the head, forming a gradient of its dark back coloration to white or gray, making a sort of “Y” in the darker back area between the patches. The reef manta ray also has a white belly, often with dark spots primarily between and below the gills but also along the margins of the belly. See image below.

Help us identify and track mantas by reporting any sightings.

You can report sightings by going on Manta Pacific Research Foundation or Hawai‘i Association for Marine Education and Research websites. If able, please take photos of the underside of the manta, showing their spot pattern. They will help you identify which manta species it is, and if it is a new one, you can name it.

Check out a video about the Giant Oceanic Manta Ray, presented by the PSP program.

Literature Cited

- Young, C.N., Carlson, J., Hutchinson, M., Hutt, C., Kobayashi, D., McCandless, C.T., Wraith, J. (2017, December). Status review report: oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinius longimanus). Final Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources.

- NOAA Fisheries (2023, August 30). Oceanic Whitetip Shark.

- SharkTaggers. (2019). Hawai‘i community tagging program: HCTP. Hawai‘i Community Tagging Program.

- Seki T., Taniuchi T., Nakano H. and Shimizu M. (1998) Age, growth and reproduction of the oceanic whitetip Shark from the Pacific Ocean.

- Maui Ocean Center. (2023). Scalloped Hammerhead Shark.

- Miller P., Domingo A., & Forselledo R., Mas F. (2022). Scalloped hammerhead.

- NOAA Fisheries (2023, January 30). Scalloped Hammerhead Shark.

- William T White, Shannon Corrigan, Lei Yang, Aaron C Henderson, Adam L Bazinet, David L Swofford, Gavin J P Naylor. (2018, January 1). Phylogeny of the manta and devilrays (Chondrichthyes: mobulidae), with an updated taxonomic arrangement for the family.

- NOAA Fisheries (2023, September 11). Giant Manta Ray.

- Marshall, A.D., Compagno, L.J.V. and Bennett, M.B. (2009). Redescription of the genus Manta with resurrection of Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) (Chondrichthyes; Myliobatoidei; Mobulidae). Zootaxa.

- Kashiwagi T, Marshall AD, Bennett MB, Ovenden JR. (2012, July). The genetic signature of recent speciation in manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris).

- Miller, M.H. and C. Klimovich. (2017, September 01). Endangered Species Act Status Review Report: Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris) and Reef Manta Ray (Manta alfredi). Report to National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources, Silver Spring, MD.

- Kitchen-Wheeler A-M (2013) The behavior and ecology of Alfred mantas (Manta alfredi) in the Maldives (Doctoral dissertation). Newcastle University, School of Biology. April 2013.