Hawai‘i Coral Restoration Nursery

The Hawaiʻi Coral Restoration Nursery (HCRN) is located at DAR’s Ānuenue Fisheries Research Center (AFRC) on Sand Island, O‘ahu, and is part of an innovative State of Hawaiʻi driven approach towards mitigating both planned (coastal development and dredging activities) and unplanned (vessel groundings and pollution spills) impact events on Hawaiian coral reefs. The HCRN uses small corals to rapidly grow large coral colonies at a land-based coral nursery which are then outplanted to damaged and degraded reefs. More information about the HCRN’s fast-growth process, including sourcing corals, grow-out, and outplanting can be found in the links below.

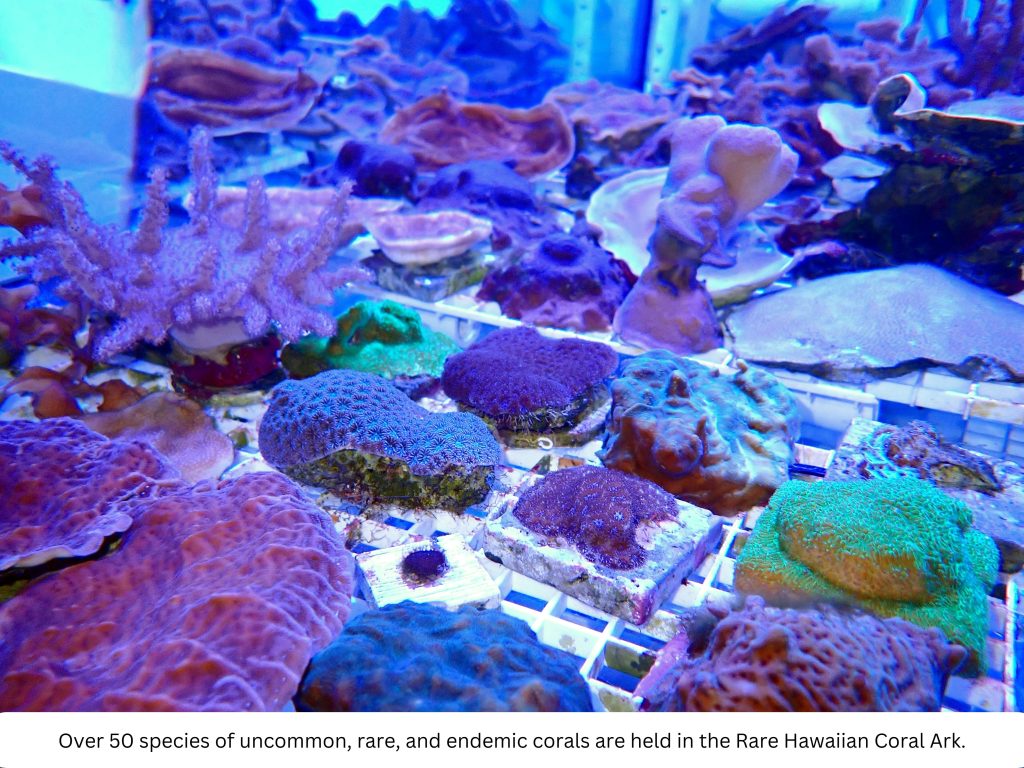

To protect the biodiversity of Hawaiian corals from the threat of extinction, the HCRN also houses part of the Rare Hawaiian Coral Ark, a multi-agency effort started at the HCRN in 2015, which preserves a live repository of rare, uncommon, and endemic Hawaiian coral species. In the event that a rare Hawaiian coral species goes extinct in the wild, the HCRN has the ability to grow representatives of that species held in the Ark and reintroduce them back into their native habitat. More information about the HCRN’s Rare Hawaiian Coral Ark can be found below.

Coral restoration in Hawaiʻi presents several unique challenges. Due to geographic isolation, Hawai‘i has one of the highest rates of endemism of any ecosystem worldwide; this includes both corals and coral reef-associated organisms such as fish, invertebrates, and limu (algae). This means that much of this incredible marine life cannot be found anywhere else in the world. Additionally, compared to many other reef systems in the world, Hawaiʻi has some of the slowest growing corals, with most reef-building corals growing 1 – 2 cm per year, compared to 10 – 20 cm per year in the South Pacific and the Caribbean. These challenges highlight why coral restoration is incredibly important as bleaching events, vessel groundings, coastal development, pollution, and climate change all pose serious threats to the coral reef community.

Because coral reefs host many unique organisms, coral restoration demands a high level of knowledge about coral reef ecology and professional coral husbandry. For these reasons, and in compliance with laws governing Hawaiian corals as a natural resource, the HCRN adheres to protocols developed through years of experience studying, growing, and restoring Hawaiian reefs. The HCRN focuses on growing large corals, between 40 – 100 cm. Larger coral colonies provide far more ecological services and functions on a reef than small coral colonies, such as:

- Increased habitat for fish and invertebrates

- Greater reduction in wave energy

- Higher rates of reproduction

- Higher chance of withstanding stressful events, such as increasing water temperatures or predation

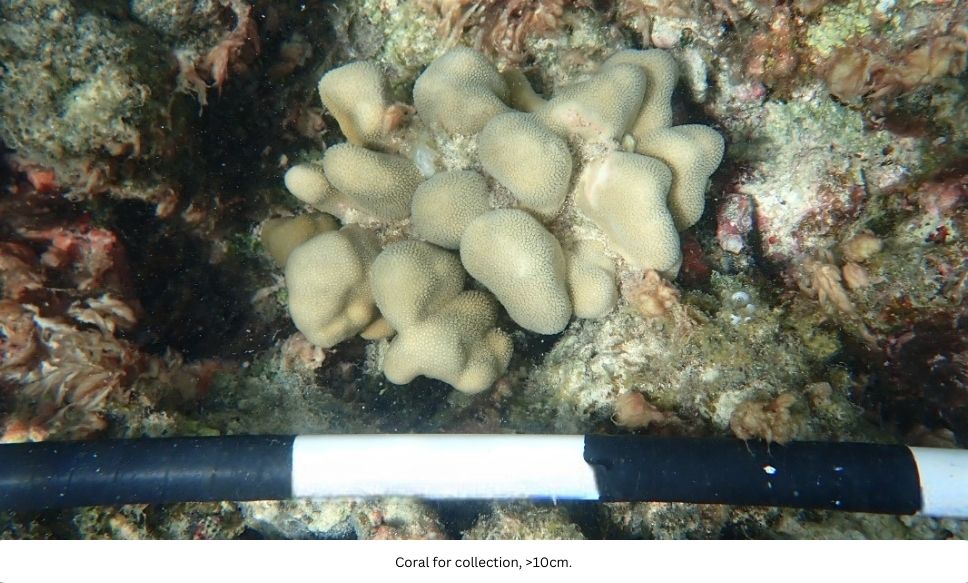

To minimize the impact to natural reefs, the HCRN prioritizes collecting corals from areas of lower ecological value, such as harbors. If certain coral species cannot be found in harbors, the HCRN targets loose or damaged corals. Often called “corals of opportunity”, these include corals that have been damaged from storms, boat grounding, or anchor damage. Corals that are loose or from a harbor contribute little to ecosystem services such as coastal protection, sand production, and tourism attraction, and therefore have a lower ecological value. By collecting these corals, quickly growing them to a much larger size, and outplanting them onto a degraded reef, the HCRN is able to vastly increase the ecological value those corals provide.

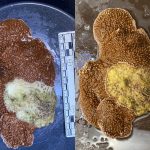

Collecting corals from harbors doesn’t come without risks. Due to the polluted nature of harbors, these corals may have a higher chance of containing heavy metals deep within their skeletons, harbor-associated diseases, or aquatic invasive species (AIS). To mitigate these risks, the HCRN follows strict quarantine and health assessment procedures for all corals entering and exiting the nursery.

Coral colonies collected for module production must meet the following requirements:

- Must be a native Hawaiian coral species

- Healthy tissue coloration and polyp extension

- Absence of visible tissue recession, disease, or recent death

- Absence of excessive algal growth

- Minimal or absence of visible AIS

- Minimal or absence of visible micropredators on colony

- Be at least 10 cm in size

Corals that meet these requirements are carefully dislodged from the substrate by HCRN staff using various tools. The process is photographed and cataloged in the HCRN database to maintain a chain-of-custody for every coral collected.

Immediately after collection, coral colonies are placed in designated quarantine tanks and are closely monitored for health concerns. While in quarantine, HCRN staff check corals daily for disease, AIS, micropredators, and other indicators of poor coral health. Once the corals have been quarantined for at least 30 days with no health issues, the corals are moved out of the quarantine area. If at any point a health issue is observed on a coral in quarantine, the 30-day quarantine period is restarted. This process allows for acclimation to the nursery setting and reduces the risk of disease, AIS, or micropredators within the nursery itself and onto a potential restoration site.

Treatment

When corals are subjected to stressful events, they are more likely to contract infections or lose tissue. The process of collection and transport from the field into the nursery is a stressful process, and to minimize the stress during these events, the HCRN uses a variety of coral-safe treatments to boost coral health and combat commonly found infections. For example, corals may be dipped in a water bath containing diluted Lugol’s Iodine. This is because iodine is a powerful astringent and antiseptic that the coral can absorb from the water to prevent or eliminate disease.

Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS)

Due to the isolated location of Hawaiʻi, AIS can pose a serious threat to native ecosystems. AIS are species that are introduced into an environment that outcompete native species, leading to a decline in overall species diversity and ecosystem function. During quarantine, any AIS found are removed and reported to the DAR Aquatic Invasive Species team. On O‘ahu, the most common AIS that threaten corals are invasive algae, such as Gorilla Ogo (Gracilaria salicornia) and Smothering Seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii and Eucheuma spp.). These invasive algae can outcompete corals for space due to their rapid growth rate.

Micropredators

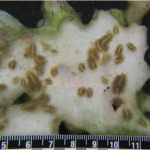

There are many animals that naturally eat coral in the Hawaiian coral reef ecosystem. Most commonly found are different species of nudibranchs (sea slugs) which eat corals in the Genus Porites, the Montipora-eating flatworm, and corallivorous snails that prey on a variety of coral species.

To get rid of micropredators, HCRN staff conduct daily health assessment checks, including manual removal of these organisms. Once the coral has been free of disease, AIS, and micropredators for at least 30 days, it can then undergo the fast-growth process.

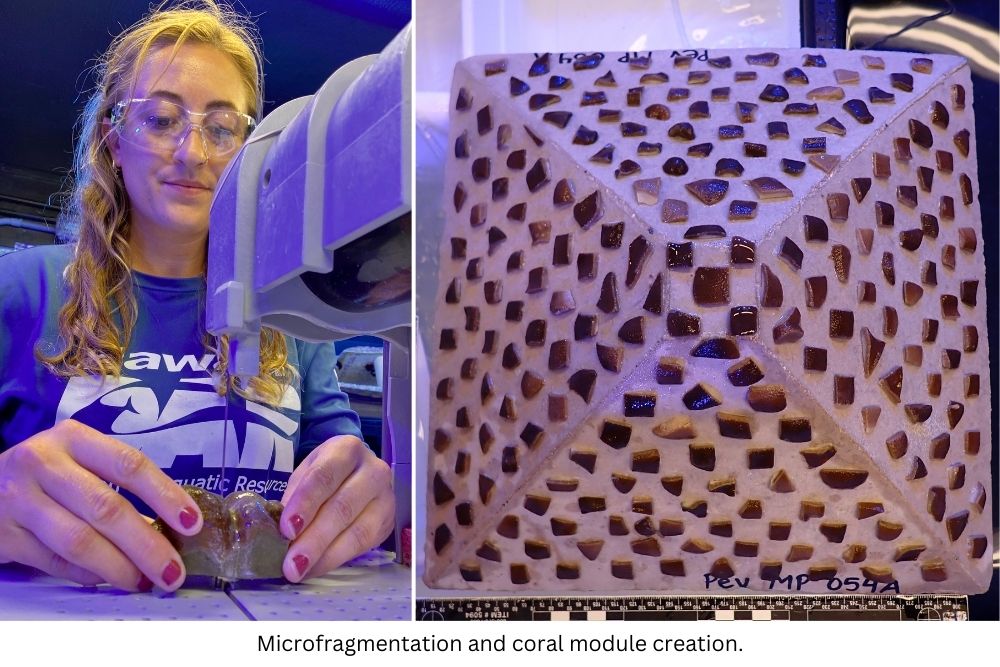

A coral colony is made up of thousands of small, individual animals called coral polyps, as well as a calcium carbonate skeleton. As a polyp grows, it can divide through asexual reproduction to produce coral polyps that are genetic clones of itself. When a piece of coral is cut or broken in half in the wild, the row of polyps along the freshly-exposed edges begin to grow a new row of coral polyps along the surface, which then begin to grow another new row of coral polyps. By taking advantage of this natural method of asexual reproduction and outward growth, the HCRN can grow large corals much faster through a process called microfragmentation.

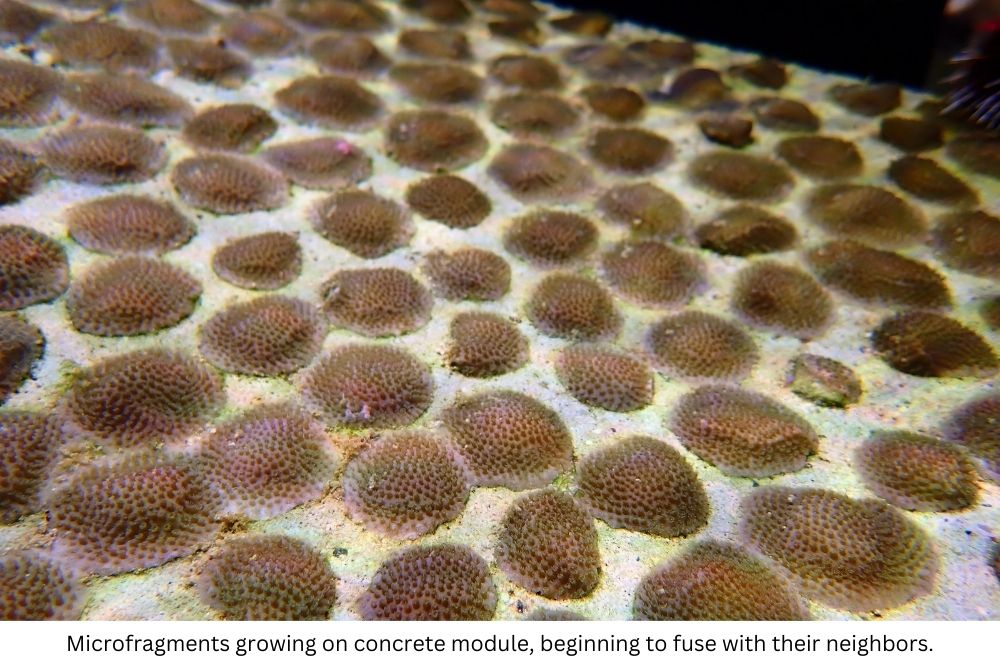

HCRN staff use a specially-designed diamond blade band saw to cut a coral colony into 1 cm x 1 cm square pieces (microfragments) which creates more edges for new tissue growth and increases the surface area to volume ratio. If a 10 cm x 1 cm coral is cut into 100 microfragments, each 1 cm x 1 cm, the coral now has a total perimeter of 400 cm for new tissue growth to occur. After the coral is microfragmented, coral-safe superglue is used to attach fragments onto cured concrete pyramid modules made at the nursery.

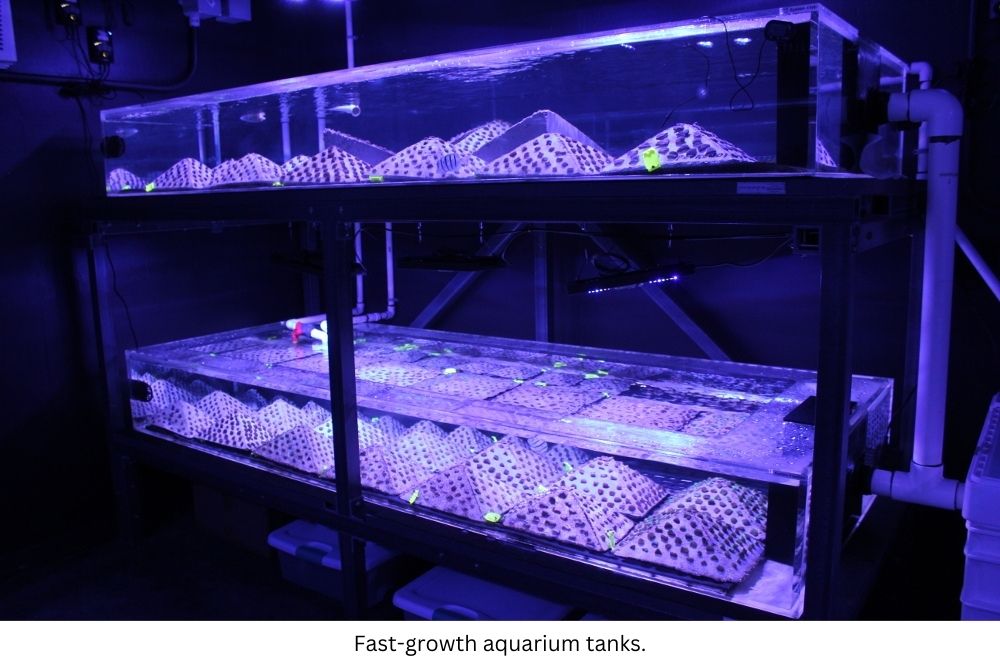

The coral module is placed in a specialized aquarium (“grow-out tanks”) to complete the fast-growth process. Using these concrete modules as a base, microfragments have an initial surface they can grow onto. All the microfragments on the module are from the same source material (i.e. the same genotype), so as they grow across the surface of the concrete module and meet up with their neighboring microfragments, they will fuse to form one large adult colony.

In the grow-out tanks, all aspects of the environment are controlled to create optimal growth conditions. Water temperature and flow, salinity, essential minerals, light, and coral food are a few things the HCRN can modify to aid coral growth. The HCRN’s professional team of aquarists check on the health of the corals to ensure tank conditions remain optimal and take quick action if issues arise. The process is photo documented and entered into the HCRN database to maintain a chain-of-custody for every coral module grown.

Once the concrete module is completely covered in coral tissue, it is almost ready to be outplanted onto a natural reef. The fast-growth environment at the HCRN is very different from the natural reef environment, so colonies are acclimated to the specific conditions found at the target restoration site. Coral outplants are re-introduced to natural sunlight, photoperiod, water quality parameters, and restoration site temperatures in outdoor acclimation tanks for at least 30 days before they are ready for life in the ocean. The entire process is photo documented and entered into the HCRN database to maintain a chain-of-custody for every coral module grown at the HCRN.

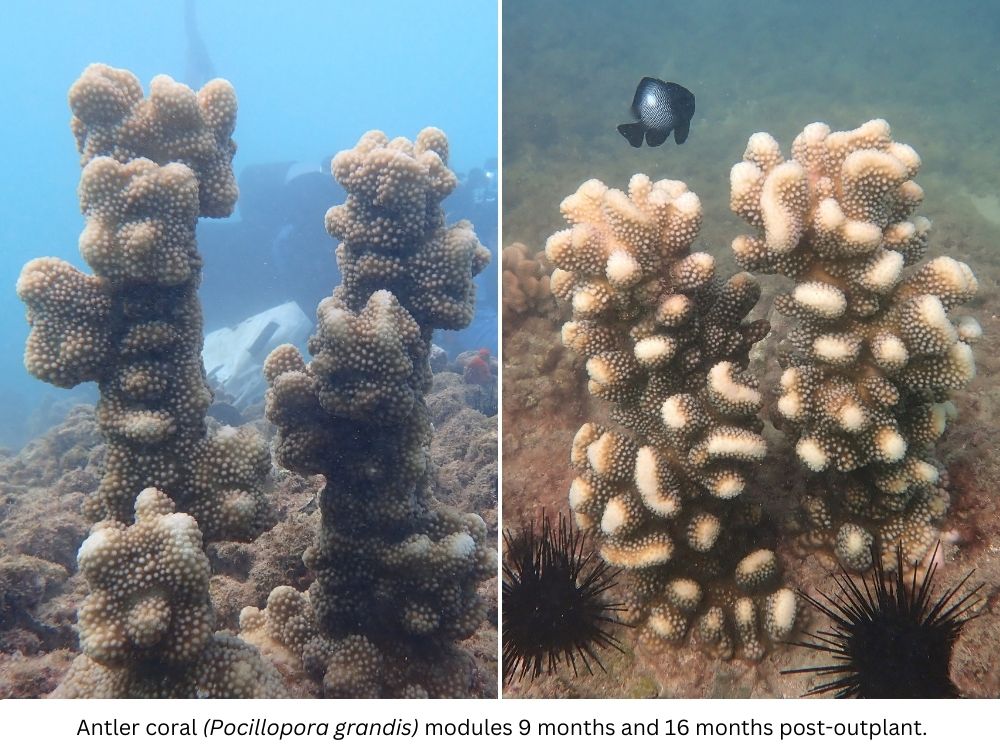

During the outplanting phase, HCRN staff secure coral modules onto the reef in target restoration areas. A baseline assessment is completed at the outplant site before outplanting modules, which provides information necessary to determine whether the target site is appropriate for coral restoration, including which coral species should be outplanted.

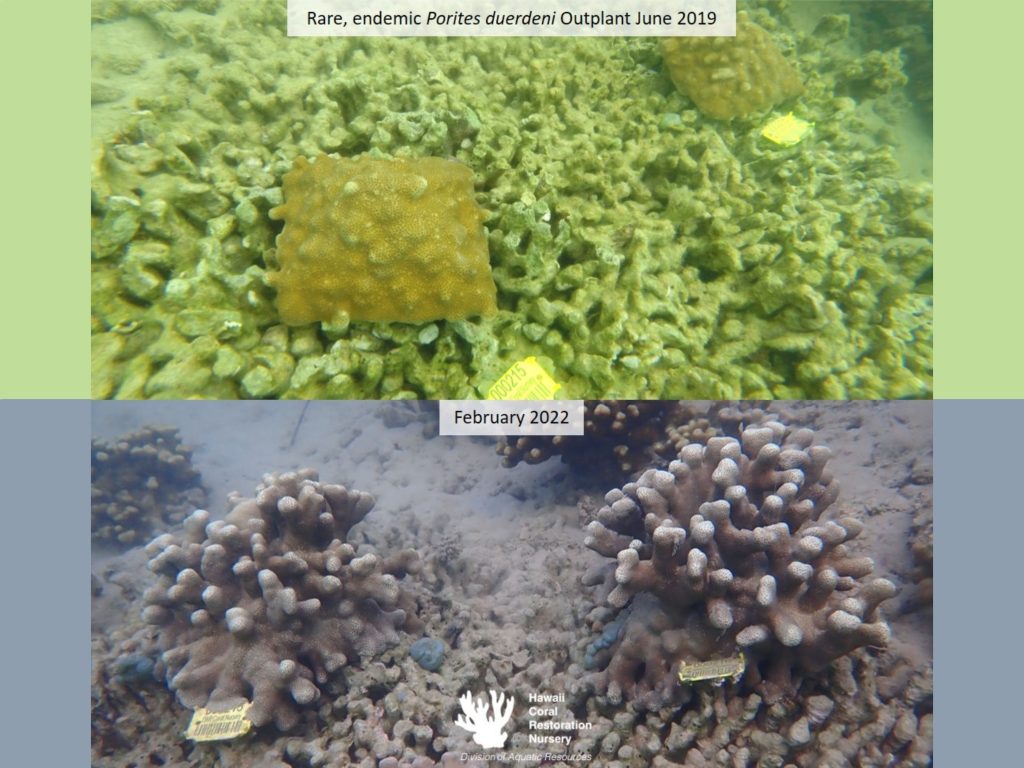

During the baseline assessment, natural corals growing adjacent to the outplanting site are selected as reference control corals. These control corals are used to compare coral health and growth between areas containing naturally occurring coral colonies and outplanted modules to analyze long-term restoration outcomes. Over time, the outplanted coral will begin to blend into the natural environment, both in terms of color as well as profile appearance.

To prepare the site to receive a new coral, HCRN staff clear algae and sediment off the substrate where the coral module will be attached. Divers attach the coral to the reef using a two-part marine grade epoxy placed on the underside of the concrete module. Outplanting is usually performed during fall, winter, and spring to allow the outplanted coral to acclimate to life in the ocean before experiencing the warm water temperatures of summer. During summer, ocean temperatures in Hawaiʻi typically rise over 80°F, and even warmer temperatures could induce bleaching on a recently outplanted coral that has not yet fully acclimated to its new environment. The entire outplanting process is photo documented and entered into the HCRN database to maintain a chain-of-custody for every coral outplanted by the HCRN.

The HCRN routinely monitors outplanted coral colonies to ensure optimal health, survival, and growth. Outplants are monitored very frequently in the first three months after the outplanting event, and then gradually less frequently as the coral becomes a permanent part of the ecosystem at the outplant site.

HCRN staff look for these key indicators of coral health when monitoring corals:

-

- Size and growth of the outplant, including new coral growth

- Any presence and degree of outplant tissue paling or bleaching

- Any presence and degree of outplant tissue death

- Any presence of any known coral disease

- Any indication of corallivores present

- Any presence of aquatic invasive species

- Any presence of competitors directly affecting coral health and growth

- Any impacts of sedimentation

- Obvious breakage of coral colony or outplant structure

These monitoring sessions are photo documented and entered into the HCRN database to maintain a chain-of-custody for every coral outplanted by the HCRN.

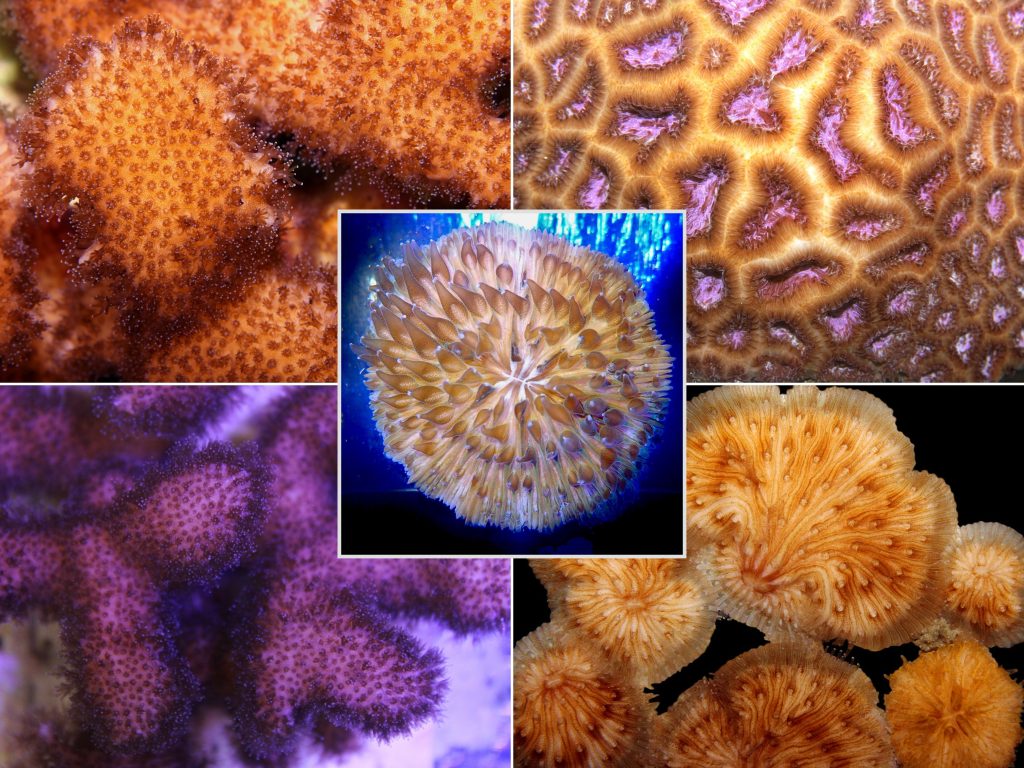

The HCRN holds the Rare Hawaiian Coral Ark, a collection of living coral colonies of rare, uncommon, and endemic Hawaiian coral species. Coral species naturally exist at differing levels of rarity, and the rarer species are more vulnerable to potential impacts to their populations, which may result in extinction. Up to 20% of the coral species in Hawaiʻi are endemic, meaning they only exist within the Hawaiian Islands. With no replacement pool outside of Hawaiʻi, it is imperative to protect these endemic species, some of which are restricted to a single bay or a single reef throughout the Hawaiian Islands. A wide range of endemic fish and invertebrates have coevolved with Hawaiian endemic and rare corals and have come to rely on the presence of these corals, so an event that causes the extinction of the coral may have cascading effects. The HCRN maintains living specimens of native and endemic coral species as insurance against catastrophic events (e.g., wide-scale bleaching) that could threaten or cause extinction of endemic or rare native species. The HCRN actively collaborates with the Maui Ocean Center to maintain and expand this Ark.

The importance of the Rare Hawaiian Coral Ark has been demonstrated with the restoration of a rare endemic Hawaiian species on the island of O‘ahu. In anticipation of a 2015 summer bleaching event, the HCRN collected multiple small pieces of Knobby Finger Coral (Porites duerdeni), an endemic species that has only been found within Kāneʻohe Bay on O‘ahu. Unusually high water temperatures during the summer of 2015 caused mass coral bleaching and mortality across the state, and remaining living colonies of P. duerdeni could not be found in the Bay. Due to the proactive response by the HCRN, the only known living specimens were located in the Ark. When it was determined that this species could be locally extirpated or possibly extinct, staff microfragmented pieces of coral previously collected, grew them on small modules, and in early 2019 outplanted these modules back into their native Kāneʻohe Bay. This was the first known reintroduction of a possibly extirpated coral species into its native habitat. Four years later, the outplants are healthy and continue to grow.

Corals in the Rare Hawaiian Coral Ark

| Acroporidae: |

Acropora sp., Anacropora sp., Montipora dilatata*, Montipora flabellata*, Montipora patula*, Montipora studeri |

|

Agariciidae: |

Gardineroseris planulata, Leptoseris foliosa, Leptoseris hawaiiensis, Leptoseris incrustans, Leptoseris mycetoseroides, Leptoseris papyracea, Leptoseris scabra, Leptoseris tubulifera*, Pavona maldivensis |

|

Dendrophylliidae: |

Cladopsammia eguchii, Tubastraea coccinea, Tubastraea diaphana, Rhizopsammia verrilli |

|

Faviidae: |

Cyphastrea agassizi, Cyphastrea ocellina, Leptastrea bewickensis, Leptastrea transversa, Leptastrea pruinosa |

|

Fungiidae: |

Cycloseris sp. (red)*, Cycloseris vaughani, Diaseris fragilis, Diaseris distorta, Fungia (Lobactis) granulosa |

|

Pocilloporidae: |

Pocillopora ligulata*, Pocillopora molokensis* |

|

Poritidae: |

Porites cf. annae, Porites compressa*, Porites duerdeni*, Porites evermanni*, Porites hawaiiensis*, Porites cf. lichen, Porites monticulosa, Porites rus, Porites solida |

|

Siderastreidae: |

Coscinaraea wellsi, Psammocora explanulata, Psammocora profundacella, Psammocora nierstraszi, Psammocora stellata, Psammocora verrilli* |

|

Soft Corals & other: |

Sarcothelia edmondsoni*, Sinularia molokensis*, Clavularia sp., Heteractis malu |

*Asterisks denote endemic species.

Learn more about our latest project!

Check out the project webpage here!

2024

Restoration of Rare Coral Species Continues – 5 Years Later | State of Hawaii DLNR News Release

Corals Reattached at Kewalo Basin After Suspected Anchor Damage | State of Hawaii DLNR News Release

Restoring Hawaii’s Coral Reefs, a Mauka to Makai: Our Kuleana Story | PBS Hawai‘i

VIDEO: These Coral Pyramids are Helping Hawaii’s Reefs in a Big Way | PBS Hawai‘i

2023

Restoration | Friends of Hanauma Bay

Five Coral Restoration Modules Planted in Hanauma Bay | Friends of Hanauma Bay

Coral restoration project at Hanauma Bay | Spectrum News

2021

Emergency Restoration Action Saves Broken Coral | State of Hawaii DLNR News Release

Emergency coral rescue and restoration efforts underway at Honolulu Harbor | Star Advertiser

Emergency Restoration Action Taken to Save Corals Damaged During Dredging | Maui Now

Dredging Operations in Harbor Channel Cause Serious Coral Damage | State of Hawaii DLNR

2020

Hanauma Bay being restored with nursery-grown coral | West Hawaii Today

DLNR begins coral restoration project at Hanauma Bay | KHON2

Restoration Begins at Hanauma Bay with Nursery Grown Coral | State of Hawaii DLNR News Release

Nursery-grown corals find new home at Hanauma Bay | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

Coral Restoration Nursery | Hawaii Sea Grant

2019

Episode 566: Office of Tech Transfer and Coralpalooza | Bytemarks Cafe

Sustaining Hawaii’s Coral Restoration Nursery to save our coral reefs | Hawaiian Electric

Hawaii’s Coral Restoration Nursery | Pacific RISA

2018

Coral out-plantings thriving at Sand Island | The Garden Island

2016

Episode 401: Coral Restoration Nursery – May 4, 2016 | Bytemarks Cafe

Coral Restoration Nursery Opens on Oahu | Reef to Rainforest Media

Officials in Hawaii create nursery for fast-growing coral | The Seattle Times

What makes Hawaiian corals unique?

In the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant, the coral polyp or ko‘a was one of the first living organisms created along with Kumulipo and Pō‘ele, the first man and woman.

“Hānau ka uku ko‘ako‘a, hānau kāna, he ‘ako‘ako‘a, puka”

Born was the coral polyp, born was the coral, came forth

The ko‘a was then followed by the creation of urchins, sea cucumbers, sea stars, and so forth. Documentation of the ko‘a as one of the first life forms reveals how Hawaiians hundreds of years ago already recognized the importance of coral reefs and their role in sustaining marine ecosystems and themselves.

Hawaiian corals themselves are unique for a number of reasons which also require special needs for maintenance and growth in a restoration setting. The most consequential reasons are slow growth rates, low levels of biodiversity, a unique dominant growth form, and the highest level of endemism found in a reef ecosystem on the planet.

Reef-building species of Hawaiian corals grow incredibly slowly in the wild at an average growth rate of 1 – 2 cm per year. For comparison, Staghorn Coral Acropora cervicornis, a fast-growing Caribbean branching coral and likely the most commonly used species in coral restoration in the Atlantic, grows upwards of 10 cm per year. On the Great Barrier Reef corals can commonly grow upwards of 15 – 20 cm per year. Due to the slow growth rate in Hawaiʻi, nursery staff must be innovative when coming up with ways to quickly grow Hawaiian corals. This also emphasizes the importance of coral restoration, since natural recovery from impact events can take an incredibly long time.

The biodiversity on Hawaiian reefs is low when compared to other large reef ecosystems. There are only approximately 60 species of Hawaiian corals in the main Hawaiian Islands, and these occur at differing levels of rarity. For this reason, the nursery focuses efforts on maintaining these levels of diversity when restoring an impact site.

The most common Hawaiian coral growth forms are massive (mounding), plating, or small branching colonies. Other reefs in the world are dominated by branching corals. To preserve the ecosystem functions of large bouldering or plating coral, the HCRN uses specially designed modules to mimic natural coral structures while minimizing potential damage from waves and sediment.

Lastly, Hawaiian coral reef systems sustain high rates of endemism, meaning many coral species found in the Hawaiian Islands are found nowhere else in the world. This is in part due to the isolation of the Hawaiian archipelago where corals have evolved over millions of years. Up to 20% of coral species found in the Hawaiian Islands are only found here, emphasizing the need to protect these species. As there is no replacement pool for these species, cautious management decisions are required regarding endemic Hawaiian corals.

Why does the State of Hawaiʻi need a coral nursery?

Despite corals being fully protected by law in the State of Hawaiʻi, there was little mitigation conducted for direct impacts to the State’s corals prior to the HCRN. Due to multiple human impact events causing significant damage to coral reefs, such as the M/V Cape Flattery grounding in 2005 and the USS Port Royal grounding in 2009, the Division of Aquatic Resources created the HCRN as a method to mitigate these damage events.

Why is the HCRN a land-based nursery?

Elsewhere in the world, most coral nurseries are field-based (in situ), meaning they are located directly in the ocean. In situ nurseries require less maintenance and infrastructure, and therefore cost far less to run. Most of these nurseries incorporate a fishing line or rope technique where corals are suspended from a structure to hang them in the water. These nurseries often excel at naturally fast-growing species of branching corals such as Acropora, which is not a component of major reefs in the main Hawaiian Islands. Importantly, this method can only be used in calm water locations. Given the slow natural growth rates of Hawaiian corals as well as the extremely high wave energy that Hawaiian reefs encounter, field-based nurseries would not result in large corals being produced within short time frames. Because of these considerations, the HCRN is a land-based (ex situ) nursery, which means that corals are grown in tanks on land. This gives us the ability to use our fast-growth protocol to quickly grow large adult coral colonies for restoration purposes.

How successful are the coral outplants?

Across all restoration sites on O’ahu, the HCRN has approximately 90% survival of all coral outplants. This is one of the highest known success rates in the world for coral nursery outplants.

Want to provide feedback?

Fill out this Google Form to help us improve our website.

We are a small team with specialized and diverse backgrounds who are dedicated to restoring coral reefs in Hawai‘i.

Christina Jayne, Coral Nursery Curator

Christina Jayne, Coral Nursery Curator

Christina Jayne earned a B.S. and M.Sc. in Marine Biology from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California San Diego. She has worked professionally with corals and marine aquaria since 2010 and has been with the Nursery since 2018. As the Nursery’s Curator, she oversees coral husbandry operations, restoration projects, and husbandry staff.

Norton Chan, Coral Restoration Specialist

Norton Chan, Coral Restoration Specialist

Norton Chan earned a B.A. in Zoology from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and has been with the Nursery since 2015. He was previously a professional Aquarist for over 20 years at the Waikīkī Aquarium where he worked with various fishes, invertebrates, and corals from Hawaiʻi and the Indo-Pacific. Norton oversees coral husbandry in the coral module grow-out rooms, field operations, and facility maintenance.

Taylor Engle, Coral Restoration Specialist

Taylor Engle, Coral Restoration Specialist

Taylor Engle earned a B.A. in Biology from the University of Northern Iowa and started working in public aquariums in 2015. He has been with the Nursery since 2019 and oversees coral husbandry in the coral module grow-out rooms, water quality, and quarantine.

Hélène Meehl, Coral Restoration Technician

Hélène Meehl, Coral Restoration Technician

Hélène Meehl earned a B.A. in Biology from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. She was previously an aquarist at the Waikiki Aquarium and Sea Life Park, where she worked with fish, shark, rays, sea turtles and marine invertebrates from Hawai’i and the Indo-Pacific. She has been with the Nursery since March 2024 and focuses on the husbandry of fast-growth coral modules.

Nicolo Cohen, Coral Restoration Technician

Nicolo Cohen, Coral Restoration Technician

Nicolo Cohen earned a B.S. in Marine Biology with a concentration in Conservation from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. While in school he was able to work in Dr. Fogarty’s REEF Lab, which studied ex-situ coral reproduction and early life stage development of Caribbean coral species. He joined the Nursery in March of 2024 and mainly works in the coral module grow-out rooms.

Andy Kramer, Coral Restoration Technician

Andy Kramer, Coral Restoration Technician

Andy Kramer earned a B.S. in Marine Science and Biology from the University of Tampa, studying seagrass and coral reef ecology and ecosystem services. He was previously a coral biologist at SeaWorld Orlando, and joined the Nursery staff in April 2024. He focuses on quarantine of collected corals and husbandry of corals in the grow-out rooms.

Sydney Lewandowski, Coral Restoration Technician

Sydney Lewandowski, Coral Restoration Technician

Sydney Lewandowski earned a B.S. in Natural Resources and Environmental Management with a specialization in Coastal Resource Management from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. She started off as a volunteer for the Nursery before joining the staff as a Junior Technician in 2023 and started her current role in early 2025. She focuses mainly on the husbandry of fast-growth coral modules within the grow-out rooms.

The HCRN relies on a dedicated team of volunteers to help care for corals and invertebrates in the outdoor holding tanks, collect and maintain data, assist with various small projects throughout the facility, and occasionally participate in fieldwork. This opportunity provides valuable hands-on experience working with Hawaiian corals in an aquarium setting for restoration efforts.

The HCRN relies on a dedicated team of volunteers to help care for corals and invertebrates in the outdoor holding tanks, collect and maintain data, assist with various small projects throughout the facility, and occasionally participate in fieldwork. This opportunity provides valuable hands-on experience working with Hawaiian corals in an aquarium setting for restoration efforts.

We typically accept 1-2 new volunteers each school semester. Our current Volunteer Interest Form is closed. Please email [email protected] with any questions.

The HCRN periodically hosts full-time interns through the KUPU Conservation Leadership Development Program. In this 11-month program, members have to opportunity to work directly with professional coral restoration staff and receive practical training on coral husbandry, aquarium design and construction, coral outplanting and monitoring, larval rearing, phytoplankton culturing, and complete a directed research project under the supervision and guidance of DAR and Nursery staff.