Sea Turtles

Sea Turtles in Hawai‘i

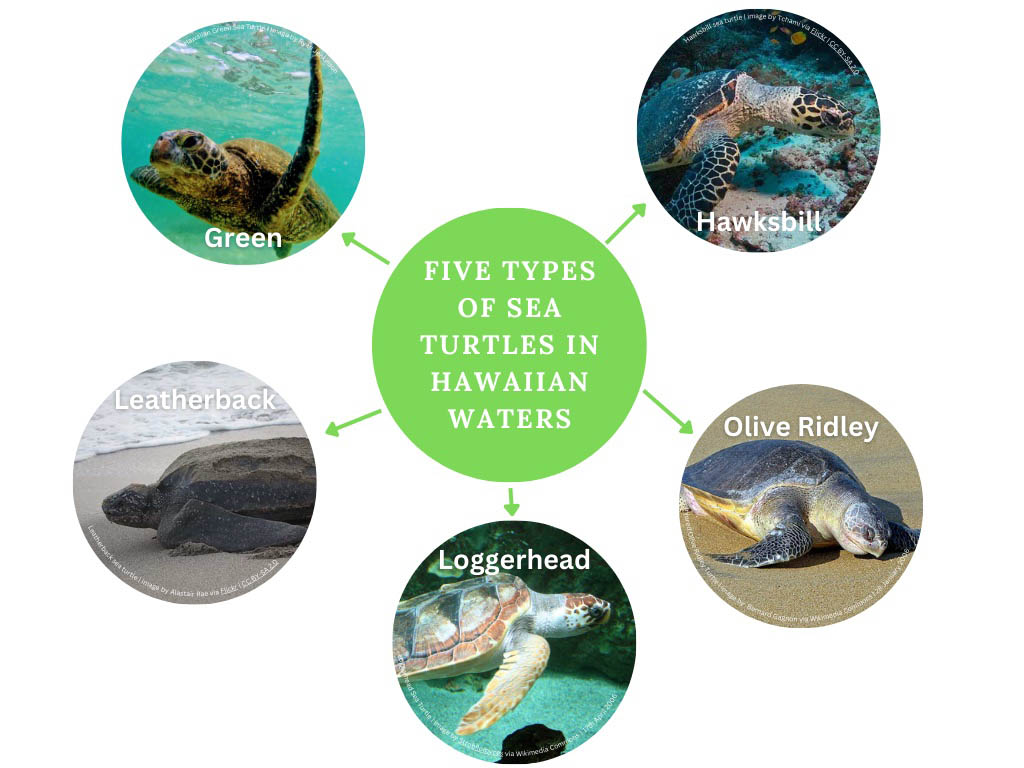

Sea turtles have been around since the time of the dinosaurs. It’s estimated that the first marine turtles existed 120 million years ago. Now, there are seven different species of sea turtles throughout the world. These reptiles, which breathe air, are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical ocean waters. Five of these sea turtle species inhabit Hawaiian waters: the green (honu, or Chelonia mydas), hawksbill (honu‘ea, ʻea or Eretmochelys imbricata), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), loggerhead (Caretta caretta), and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea).

The green sea turtle or “honu” is the most commonly encountered sea turtle species on reefs (and beaches) in Hawaiʻi. Hawksbills or “honu ʻea” (or sometimes called ʻea) are the second most common, however they are rarely observed due to their low population numbers. Leatherbacks, loggerheads, and olive ridley sea turtles are rarely seen in the nearshore coastal waters, but they may be seen further offshore in pelagic waters, primarily outside of state jurisdiction (which extends three miles seaward from the Hawaiian Archipelago.

All sea turtles in Hawai‘i are protected by the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and additionally protected by Hawai‘i Revised Statutes Chapter 195D (HRS) and Hawai‘i Administrative Rules (HAR) 13-124. Globally, their levels of protection vary by species, country, and the various subpopulations of each species.

Green Sea Turtle

Hawaiian name: Honu

Scientific name: Chelonia mydas

Description and Natural History

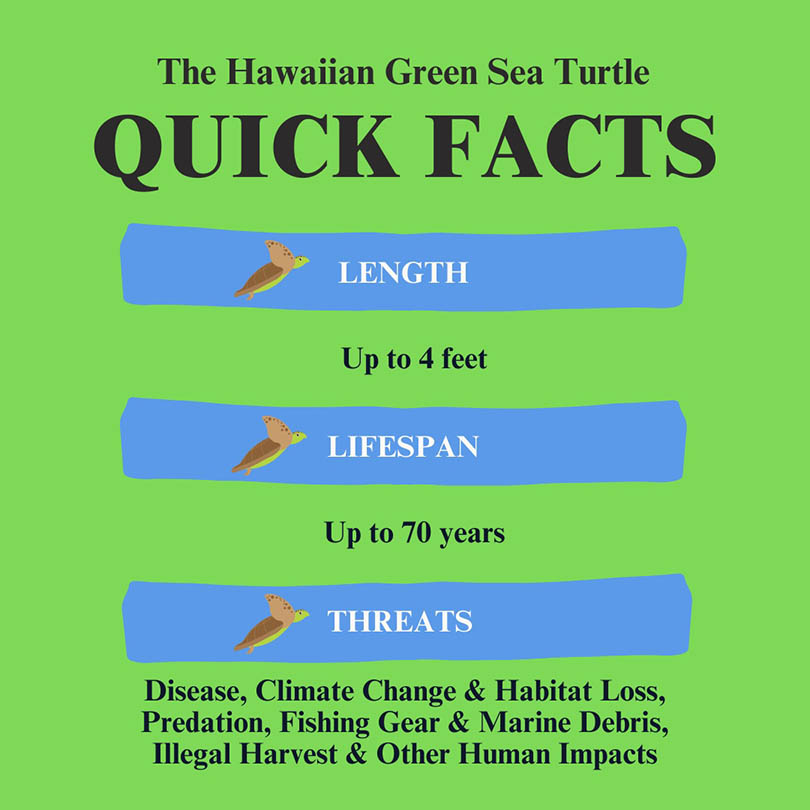

The green sea turtle is found worldwide and is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle in the ocean. It is the most frequently observed sea turtle swimming in Hawaiian waters and the only sea turtle in Hawaiʻi that exhibits basking behavior (resting) on the beach. Green sea turtles can weigh over 350 pounds, measure 3-4 feet in length, and are estimated to live up to 70 years or more [1]. The word for green sea turtle in the Hawaiian language is honu.

In old Hawaiʻi, green sea turtles were thought to be the property of ali‘i, or chiefs. According to the state of Hawai‘i’s Hawaiian Cultural Practitioner for Marine Animal Strandings, Kahu Dane Maxwell, they were occasionally raised in loko iʻa (fishponds) for consumption, their bones were carved into ornaments and fishhooks, and their shells served as storage devices [2]. Others would view green sea turtles as their deities (ʻaumākua), worshiping and caring for them.

In the 1800s, ships from Europe, Asia, and North America started visiting the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) and harvesting sea turtles for commercial trade and subsistence. By the 1900s, green sea turtles were found in every Honolulu market and restaurant, and commercial fishermen needed licenses to hunt sea turtles and file catch/harvest reports [3]. However, hunting green sea turtles had officially become prohibited in 1978 since they were designated under the ESA, and their population numbers had almost completely been annihilated in Hawaiʻi [3].

Today, the green sea turtle is protected by federal and state laws and is still regarded as ʻaumākua by many Hawaiians.

Status and Protection

Green sea turtles are found worldwide (with 11 distinct population segments (DPS) listed under the ESA) and nest in over 80 different countries. In the United States green sea turtles are primarily found in the Hawaiian Islands, U.S. Pacific Island territories, Puerto Rico, Florida and the Virgin Islands [3]. Green sea turtles in Hawaiʻi are classified within the Central North Pacific (CNP) DPS. They are listed as threatened under the ESA which means that although their overall population numbers have increased, they may become endangered in the foreseeable future due to continued threats like climate change, light pollution, habitat loss (reductions or degradation to nesting beaches), fishing line entanglements, and more. As of October 2025, their listing has been downgraded from Endangered to Least Concern under the International Union for Conservation Nature (IUCN). This is thanks to decades of conservation work done. Green sea turtles are also protected by Hawai‘i state law: HRS Chapter 195D and HAR 13-124.

The Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR)’s Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) is the primary state agency responsible for protecting and recovering green sea turtles in Hawaiʻi. DAR shares responsibility with two federal agencies: (1) U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) which has jurisdiction when green sea turtles are on land basking or nesting; and (2) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries which has jurisdiction over sea turtles when they are in the water. NMFS is also the agency that is permitted to help injured or stranded sea turtles.

Hawaiian green sea turtle nesting populations have increased over the last two decades by 5% per year, with almost 500 females nesting annually (compared with 67 nesting turtles in 1973) [3].

Diet and Habitat

Nearshore coral reefs are key foraging habitat for green sea turtles. Although they are known to eat jellyfish and other small invertebrates occasionally, adult honu are primarily herbivorous and feed primarily on different species of macroalgae or seaweed (known locally as “limu”) [1]. Green sea turtles are named for the color of their body fat caused by their mostly vegetarian diet. Their feeding grounds are commonly associated with coral reefs and shallow benthic areas such as rocky outcroppings or seagrass/algal beds.

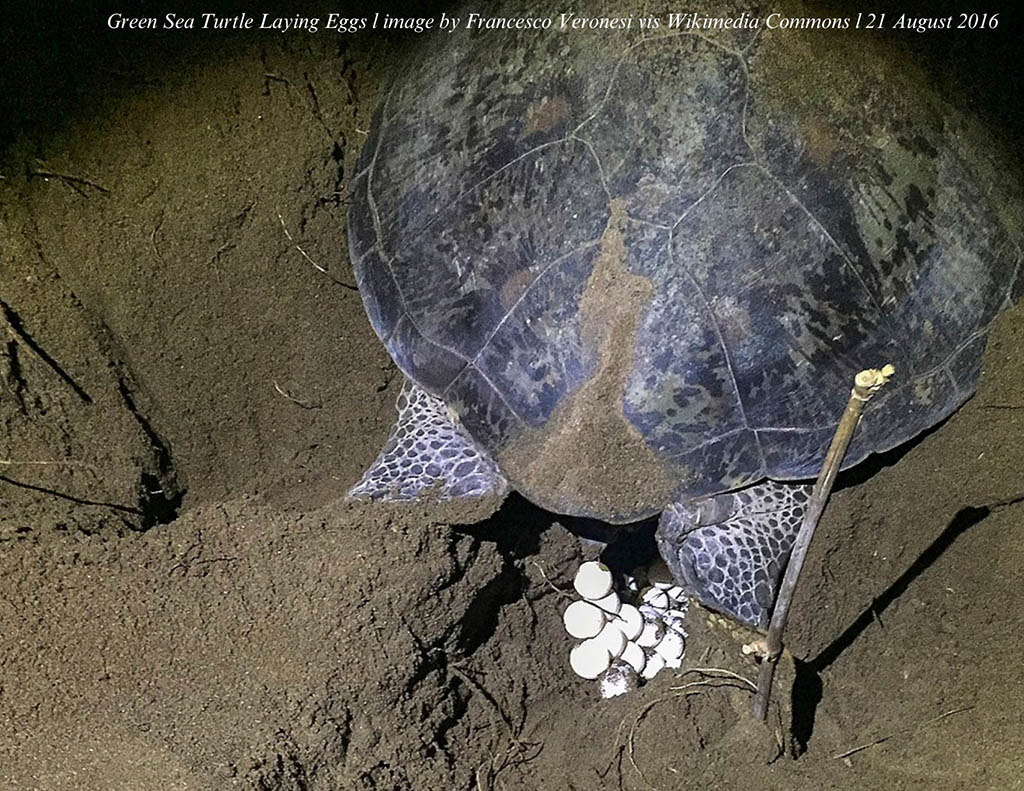

Reproduction and Nesting

An estimated 96% of all Hawaiian green sea turtle populations nest on a small atoll called the French Frigate Shoals, or Lalo [4]. This atoll is located in the NWHI within Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Green sea turtles also nest in the Main Hawaiian Islands, more commonly in the northernmost islands.

Green sea turtles are slow to mature sexually, and the age of first reproduction is estimated to be between 25 and 35 years [3]. The nesting season ranges from late April through late October. Females generally only nest every two to five years, undertake reproductive migrations, and return to nest on a beach in the general area where they themselves hatched decades earlier. Females can lay multiple clutches of eggs, numbering over 100 or more eggs per nesting season [2]. They will nest every two weeks over several months before leaving the nesting area and returning to their foraging grounds [3].

The sex of each turtle is determined by the temperature at which it incubates, which is called temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD). Research shows that if a turtle egg incubates below 27.7°C (or 81.86°F), the hatchling will be male, whereas the corresponding hatchling will be female if the egg incubates above 31°C (or 88.8°F) [5]. We like to remember this phenomena with the phrase, “hot chicks and cool dudes”. Temperatures that fluctuate between the two extremes will produce a mix of male and female baby turtles. Hatchlings that emerge from the nest will head towards the ocean, usually guided by moonlight. Honu hatchling typically occurs from August through November. Unfortunately, turtle eggs and hatchlings face many challenges along the way. They must escape predation by native and invasive predators on the beach, such as dogs, cats, crabs, sea birds, and mongoose. In addition, light pollution, coastal development, and marine debris can create obstacles that prevent or delay the hatchlings from finding their way. Once they reach the ocean, they also must escape from larger fish once to avoid being eaten. To do so, they are thought to swim offshore to avoid predation in nearshore waters. Few hatchlings will survive to adulthood, with estimates ranging from one sea turtle that survives to every thousand hatched to the extreme of one survivor to every 10,000 [6].

Threats

Although the green sea turtle has shown encouraging signs of recovery after more than 40 years of state and federal protection, many threats remain.

Disease

The primary disease that affects green sea turtles is a type of herpes virus transmitted between turtles called fibropapillomatosis (a.k.a. FP). It is a viral disease with a worldwide, circumtropical distribution, found mainly in coastal habitats where green sea turtles are more common. FP is spread by direct contact or secondary vectors such as parasites, barnacles, or cleaner fish [7].

FP causes tumors that are generally considered benign but can exist externally and internally anywhere on the turtle’s body. Internal tumors can disrupt normal organ function and cause mortality, while external tumors can impair critical functions such as sight, swimming, feeding, buoyancy, predator avoidance, mating, and more [1].

Additionally, tumors can more easily become entangled in fishing gear or other marine debris, which can also lead to a premature death. No methods currently exist for controlling or treating FP; however, mitigating agricultural run-off and improving wastewater treatment infrastructure in nearshore regions may reduce the prevalence of the disease. Although FP has declined over the past decade, it persists in the Hawai‘i population. Learn more about fibropapillomatosis here.

Predation

Sharks prey on green sea turtles as part of the natural food chain. If you happen to see a shark pursuing or eating a turtle, please let the shark continue its meal and do not interrupt natural predation.

Climate Change and Habitat Loss

Like many marine species, green sea turtles are threatened by global climate change. Sea level rise and extreme storms are already impacting green sea turtle nesting habitat. The erosion of islands within French Frigate Shoals (Lalo), an atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, is a prime example of this issue. Beginning in the late 1990s, some of the largest islands in the atoll began to wash away. In 2018, hurricane Walaka went right over Lalo and completely submerged East Island, one of the primary green sea turtle nesting islands. East Island has still not fully returned in 2023. Nesting habitat loss is predicted to continue in the NWHI with sea-level rise and increased storm / flooding activities predicted with a warming climate.

In the Main Hawaiian Islands, nesting locations have been lost due to erosion and coastal development. But in recent years, there are turtles nesting on popular beaches again for the first time in years.

Additionally, climate change may potentially skew the sex ratios in the population towards more females. Since green turtles demonstrate temperature-dependent sex determination, warmer temperatures may mean higher rates of females than males, which may cause declines in the future due to an imbalance of males vs. females. Evidence of this phenomena has already been noted across the U.S. Eastern seaboard with other species of marine sea turtles.

Fishing Gear/Marine Debris Entanglement

The foraging and diving behavior of sea turtles makes them particularly vulnerable to entanglement in debris or discarded fishing gear. Young turtles utilize floating objects for food or shelter and may accidentally become entrapped. Marine turtles often use oceanic fronts and currents to move through the waters where debris congregates, thus increasing potential entanglement risk. In particular, debris such as fishing lines, hooks, and nets pose the greatest risk as these objects can wrap around the animal’s appendages and prohibit them from surfacing to breathe, swim effectively, avoid predators, eat, or reproduce. Sea turtles of a variety of species have also been shown to consume plastics in Hawaiian waters. Visit our Fishing around Protected Species webpage to learn how to fish around Hawai‘i’s protected species properly. Also please report marine debris at sea or on land to Hawai‘i’s marine debris hotline at 833-4-da-NETS (833-432-6387) or utilize DLNR’s online reporting form.

Intentional Killing/Disturbance

Unfortunately, occasional but deliberate killing, harvesting, harassment, and other forms of disturbance of green sea turtles still occurs despite current federal and state protections. Non-life-threatening impacts such as touching, feeding, or getting too close to turtles can cause stress and overexertion. To view green sea turtles respectfully, a recommended distance of 10 or more feet has been suggested by the NMFS. To learn more about how you can help green sea turtles, visit the NMFS website on responsible wildlife viewing.

Hawksbill Sea Turtle

Hawaiian name: Honu ʻea (or ʻea)

Scientific name: Eretmochelys imbricata

Description and Natural History

The hawksbill sea turtle is a medium-sized marine turtle that gets its name from its unique beak-like mouth resembling a hawk’s. Adults can be about 3 feet in shell length and weigh 250 pounds (a little smaller than green sea turtles) [8]. The beautiful “tortoise-shell” pattern on their carapace (top shell) is believed to have caused their decline, as hawksbills were hunted for years to turn their shells into jewelry, strong fishing hooks, and other ornamental objects [8]. In Hawai‘i, hawksbills are known as honuʻ ea or just ‘ea. Recent studies suggest hawksbills in Hawai‘i represent a distinct genetic stock and nesting population, but a distinct population segment has not yet been established for these turtles [9].

The hawksbill sea turtle is a medium-sized marine turtle that gets its name from its unique beak-like mouth resembling a hawk’s. Adults can be about 3 feet in shell length and weigh 250 pounds (a little smaller than green sea turtles) [8]. The beautiful “tortoise-shell” pattern on their carapace (top shell) is believed to have caused their decline, as hawksbills were hunted for years to turn their shells into jewelry, strong fishing hooks, and other ornamental objects [8]. In Hawai‘i, hawksbills are known as honuʻ ea or just ‘ea. Recent studies suggest hawksbills in Hawai‘i represent a distinct genetic stock and nesting population, but a distinct population segment has not yet been established for these turtles [9].

Status and Protection

Hawksbill sea turtles are protected federally by the ESA and locally by HRS Chapter 195D and HAR 13-124. Because distinct population segments have not been established for this species, hawksbills are listed as endangered throughout their global range under the ESA. The IUCN lists them globally as critically endangered meaning they face an extremely high risk of extinction. Like green sea turtles, the state shares the management for hawksbill turtles within state jurisdiction with the USFWS and NOAA NMFS. Hawksbills are rare in Hawaiʻi, compared to the green sea turtle, which outnumbers hawksbills by about 100 to one [10].

Diet and Habitat

The foraging sites of adult hawksbills in Hawai‘i are still being studied further but appear to be along the eastern (Hāmākua) coast of Hawai‘i island and the waters of west Maui. The diet of hawksbills seems to fluctuate based on their habitat but commonly includes marine sponges, invertebrates (like crabs and fireworms), and algae. Since their protection with other sea turtles in 1973, it has been illegal to kill hawksbill turtles for human consumption. In fact, hawksbill meat can be harmful to humans if consumed because hawksbill turtles consume sponges. Meat from hawksbill turtles can actually be toxic to humans and has at times caused widespread disease and in rare cases, even death.

Reproduction and Nesting

Hawksbill sea turtles are estimated to reach sexual maturity anywhere from 20-35 years [8]. Nesting for hawksbills in Hawai‘i appears to be exclusive to the Main Hawaiian Islands, with an estimated average of only 20-25 females nesting annually. Hawksbills are known to nest primarily along the southeast shoreline of the island of Hawai‘i, along the remote Kaʻū coastline. A smaller number of nests have also been observed on several other isolated beaches on Maui, Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i, and Kauaʻi. Nesting season for hawksbills in Hawai‘i is typically from May to December, and the average clutch size is approximately 130-160 eggs [8]. Hatchlings generally emerge after about two months of incubation and go to the ocean, where little is known about their young, pelagic life-history stage. Like green turtles, hawksbills demonstrate temperature-dependent sex determination where cooler temperatures during incubation produce males, and warmer temperatures produce females.

Threats

Predation

Because hawksbills in Hawai‘i generally nest in the Main Hawaiian Islands, eggs and hatchlings are threatened by predation from non-native animals such as cats, dogs, mongooses, rats, and pigs. In addition, they are also threatened by native wildlife including crabs and large fish. Non-native vegetation is also a threat to hawksbills as dense root systems of various species may inhibit the excavation of nest chambers or trap hatchlings as they try to emerge.

Fishing Gear/Marine Debris Entanglement

As with green sea turtles, behavior of hawksbill sea turtles makes them particularly vulnerable to entanglement in debris or discarded fishing gear. Young turtles utilize floating objects for food and shelter and may accidentally become entrapped. Marine turtles often use oceanic fronts and currents to move through the water, where debris congregates, thus increasing their risk. In particular, debris such as fishing lines, hooks, and nets pose the most risk as these objects can wrap around the animal’s appendages and prohibit them from surfacing to breathe, swim effectively, avoid predators, eat, or reproduce. Please clean up any fishing line or other debris you come across while visiting the shoreline – you could help save a life.

Climate Change and Habitat Loss

Loss of beach area due to coastal erosion and sea-level rise due to climate change limits the space available for nesting Hawksbills in Hawai‘i. In addition, coral bleaching due to increased water temperatures and ocean acidity reduces the number of marine sponges, and other benthic reef invertebrates hawksbills feed on. Lastly, a warming climate may sway sex statistics in the populations as hawksbills exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination. This could produce higher rates of females than males, which would cause an imbalance of sexes and risk declines in the future.

Intentional Take and Accidental Bycatch

Despite years of protection both federally and from the state, it is believed that intentional killing, harvest, harassment, and other forms of disturbance are still a threat to hawksbill turtles in Hawai‘i. Even non-life-threatening disturbances such as touching, feeding, or getting too close to turtles can cause stress and overexertion. Recreational shore-based fisheries (hook and line, crab trap, and gillnet) can entangle, injure, or kill turtles.

Hawksbill or Green?

How to Tell the Difference

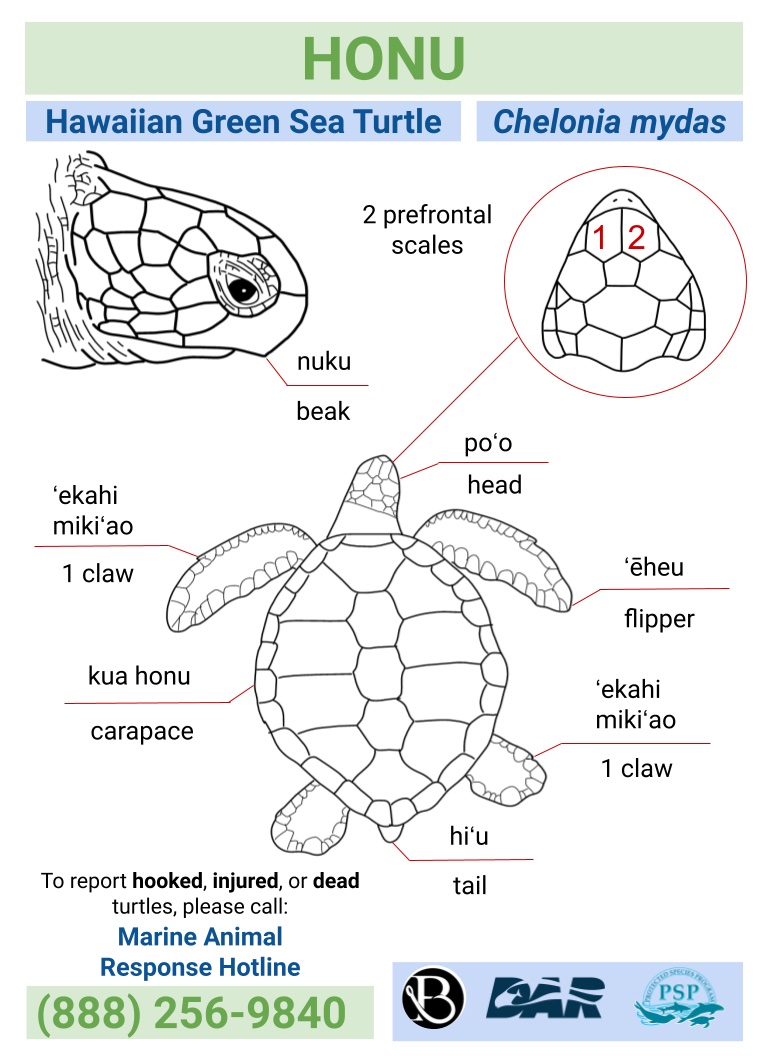

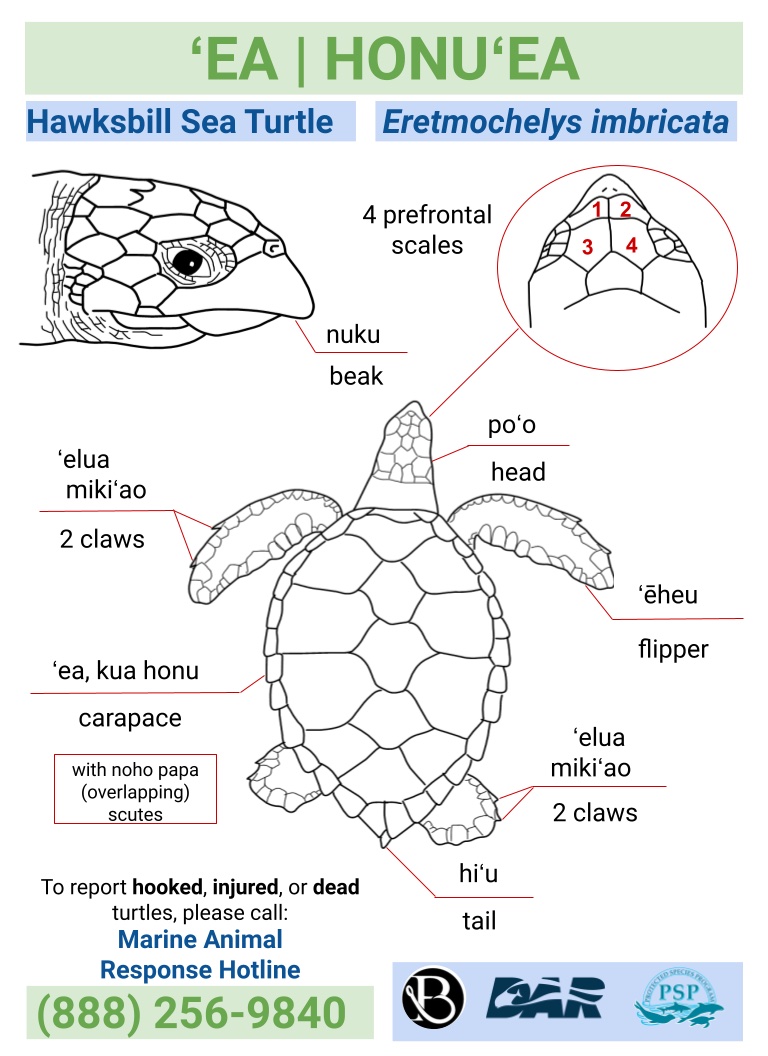

Hawksbills (honu ʻea or ʻea) have a narrow head and pointed beak, while greens (honu) have a rounded head. The number of scales between their eyes can also determine a significant difference. Hawksbills have four, while green sea turtles have two. A hawksbill’s carapace has overlapping scutes (like roof shingles) and serrated edges – which is actually the meaning of their scientific name, imbricata – whereas a green’s shell has adjoining scutes (like tiles) and smooth edges. Hawksbills have two claws per flipper, while greens have one. Hawksbill hatchlings are brown, while greens are dark gray with white trim on the flippers. Also and in general, hawksbills tend to be a bit smaller than greens and do not bask. In fact, adult honuʻea are not typically observed on land – unless it is an adult female crawling up the beach at night to dig a pit or if they are injured, sick or deceased.

What Should I Do If I See a Sea Turtle?

Give them space.

When you see a sea turtle, the best thing to do is to give them space. They may look friendly, but they have powerful beaks and can seriously injure you with a bite. Also, because the Endangered Species Act and state laws protect all sea turtles, violations of harassment or intentionally harming a turtle can result in significant fines or even time in jail. Current federal guidelines for a safe public viewing distance of sea turtles is 10 feet (3 meters). Also, please be sure to keep your dogs leashed and away from basking sea turtles and known nesting beaches.

If you see a hawksbill sea turtle, please report ALL sightings to 1-888-256-9840. Send photos to: www.HIhawksbills.org.

Report it!

If you see a hooked, entangled, or injured turtle (or other marine wildlife species in distress), always report it immediately to the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840 and keep your distance for your safety. Injured, sick or entangled animals can be unpredictable and dangerous. Non-time sensitive reports or sightings can also be reported to the NOAA NMFS marine animal stranding website.

If you witness anyone (or pet) disturbing or illegally interacting with a sea turtle please call the following numbers:

NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement Hotline at 1-800-853-1964

Hawaiʻi DLNR’s Division of Conservation Resources Enforcement (DOCARE) Hotline at 1-643-DLNR (3567)

What Should I Do if I accidently Hook a Turtle while fishing?

IT’S OK TO HELP!

If you accidentally hook a sea turtle anywhere on its body, you won’t be penalized for helping to reduce further injury.

- Call 1-888-256-9840 to report the interaction and receive guidance.

- Carefully reel the turtle in.

- Hold gently but securely by the shell.

- Cut the line as close to the hook as possible (leave the hook in to not tear or damage tissue further by attempting to remove it).

- Gently release the turtle. The less line attached or trailing from the animal, the better.

(If possible and there is someone else present, have them support you by taking an image of the entangled turtle before and after the gear is removed and share these photos with [email protected]. Mahalo!)

More ways you can help

“No white light at night.”

Use wildlife-friendly lighting near the coast (yellow/amber and shielded lights). Keep lights and beach fires to a minimum during nesting seasons (April – December). If possible and you are camping on the beach in Hawaiian, please use the red-light setting on your headlamp.

Avoid beach driving in nesting areas.

Sea turtle nesting season in Hawaiʻi runs from mid-April to November and sometimes extends into December. Off-road vehicles can crush nests, create tire ruts that trap hatchlings, and may degrade coastal habitats.

Prevent debris and rubbish from entering the ocean.

Participate in beach and reef cleanup activities and always clean up after yourself when you enjoy a day at the beach. Pay particular attention to monofilament fishing line which is of particular risk to marine turtles.

Volunteer

Volunteer with a monitoring and conservation program such as:

- UH Hilo Sea Turtle Stranding Response Team (Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

- Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park Service Hawksbill Turtle Program (Volcano, Hawaiʻi)

- Hawaiʻi Wildlife Fund (Maui and Hawaiʻi)

- Maui Ocean Center’s Marine Institute (Maui)

- Hawaiian Hawksbill Conservation (based on Maui, reports accepted statewide)

- Hawaii Marine Animal Response (Oʻahu and Molokaʻi)

- Malama Nā Honu, (Oʻahu)

- Kauai Conservation Hui email: [email protected] or call (808)651-7668

Literature Cited:

- NOAA Fisheries. (2023, July). Green Turtle.

- Maui Ocean Center. (2023). Hawaiian Green Sea Turtle.

- Seminoff, J.A et. al. (1970, January). Status Review of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) under the Endangered Species Act.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2019, August). There and Back Again: A Turtle Biologist’s Tale.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2017, April). What causes a sea turtle to be born male or female?

- NOAA Fisheries. (2015, June). A sea turtle listicle. Fascinating Facts.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2021, January). Fibropapillomatosis and Sea Turtles – Frequently Asked Questions.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2023, October). Hawksbill Turtle.

- Gaos, Alexander R. et. al. (2020, June). Conservation Genetics Hawaiian hawksbills: a distinct and isolated nesting colony in the Central North Pacific Ocean revealed by mitochondrial DNA.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2020, July). Hawksbill sea turtles are truly Hawaiʻi locals.