Hawaiian Monk Seal

Hawaiian Monk Seal – Īlio-holo-i-ka-uaua – “Dog that runs in rough water”

Hawaiian Monk Seal

Hawaiian name: ‘īlioholoikauaua

Scientific name: Neomonachus schauinsladi

Status and Protection

Status and Protection

Hawaiian monk seals are among the most endangered marine mammals in the world. They are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the International Union for Conservation Nature (IUCN). The population significantly declined since the 1950s. Although they are now protected by federal and state laws, current drivers of this decline are not certain; however, the most likely culprit is inadequate prey availability [1]. It is currently estimated that the Hawaiian monk seal population is about 1,600 seals; about 1,200 seals reside in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) and only about 400 in the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI). Hawaiian monk seals are protected federally by the ESA and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), as well as locally by Hawai‘i Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 195D and Hawai‘i Administrative Rules (HAR) 13-124. The Division of Aquatic Resources shares overall management of these species with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

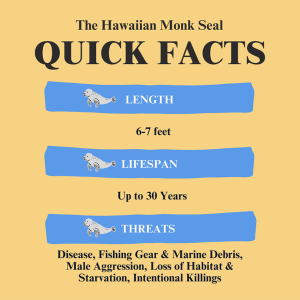

Description and Natural History

Hawaiian monk seals are part of the Phocidae family of earless seals. They are brown to light gray and can weigh upwards of 600 lbs. Females are usually slightly larger than males. They are estimated to live up to 30 years of age [1]. The Hawaiian monk seal is endemic to the Hawaiian archipelago, which means it is only found here and nowhere else in the world. Unfortunately, they were hunted to near extinction and were extirpated from the MHI many years ago. Because they face many different natural and human-caused threats, the population size remains low despite federal and state protections.

Diet and Habitat

These seals are generalist feeders, meaning they eat all sorts of prey, including sea cucumbers, eel, octopus, lobster, and various reef fish. Seals have never been observed hunting pelagic fish, such as mahi-mahi, ahi, aku, etc. Monk seals can hold their breath for up to 20 minutes and dive to depths of more than 1,800 feet [1]. When searching for food they often flip rocks with their noses to find more cryptic prey [2]. Sometimes sharks and large predator fish follow the seals around and snatch up fish that seals spook into the open [3]. Monk seals spend about one-third of their time resting on land, preferring sandy beaches, tidepools, or rocky intertidal areas to rest away from the crashing surf.

Reproduction

Reproduction

Hawaiian monk seals reach sexual maturity between five and ten years old. Many females reproduce yearly, giving birth to only one pup at a time, usually between February and July. Monk seal pups are born black and gradually change in color to grays and browns as they get older. Females will nurse for about five to six weeks, after which time the pup is weaned and will begin foraging for food on its own in shallow reefs near the pupping site [1].

Threats

Disease

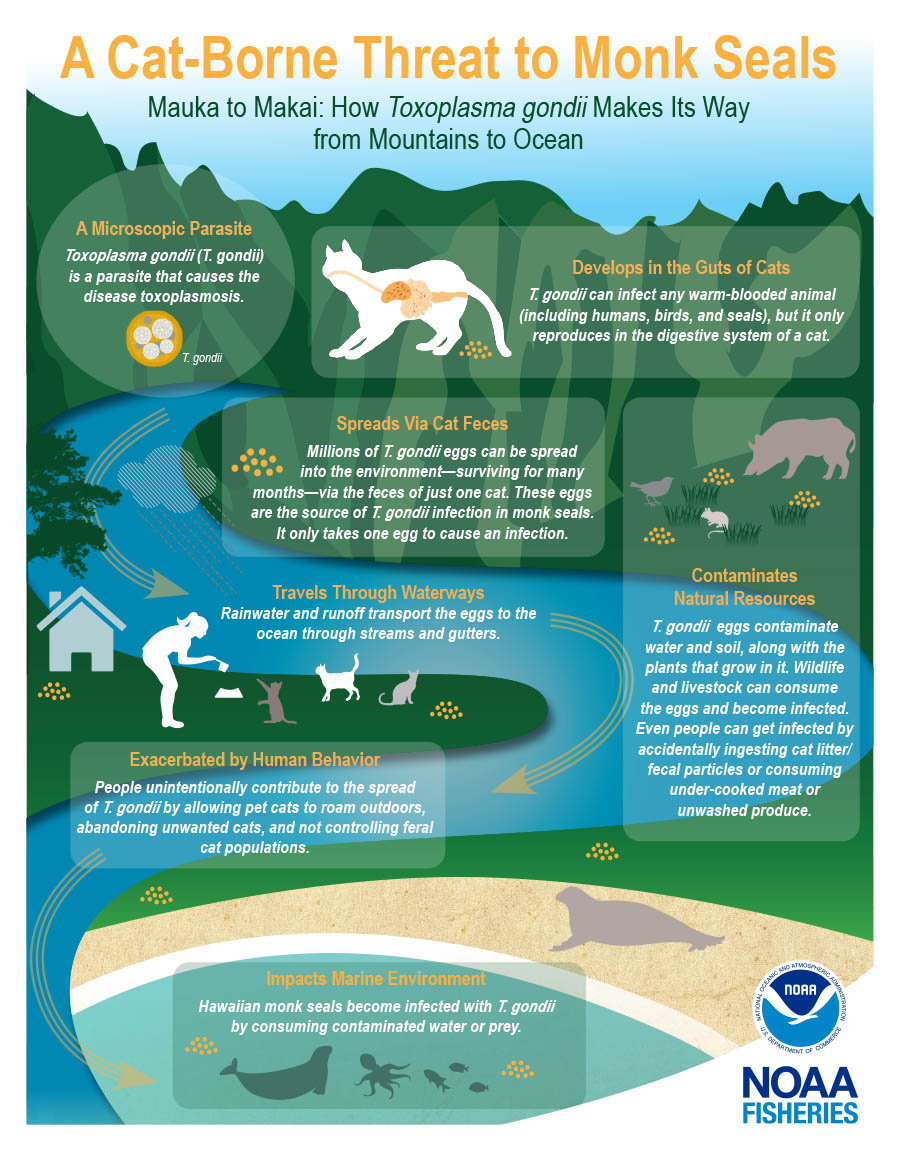

One of the primary threats to Hawaiian monk seals is a disease called toxoplasmosis, which is spread by an internal parasite called Toxoplasma gondii [4]. This parasite reproduces exclusively in the intestines of cats, and its eggs are shed in their feces. This means the large population of feral and free-roaming cats on Hawaii’s landscape are spreading this disease to the environment where it can enter the watershed and infect monk seals. Once infected, monk seals are known to suffer inflammation and dysfunction of multiple organs, loss of brain function, a compromised immune system, and even death [4]. Keeping pet cats indoors and refraining from feeding stray cats is one of the most important ways to protect Hawaiian monk seals. Please read the infographic below to understand the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii.

Learn more about toxoplasmosis and Hawaiian monk seals.

While toxoplasmosis is responsible for most disease-related deaths in Hawaiian monk seals, several other diseases, including distemper virus (morbillivirus), West Nile virus, and leptospirosis threaten them [1]. Morbillivirus can be spread from domestic dogs to monk seals via bite wounds, so keeping dogs on leashes can help prevent the spread of this disease [5]. Although NOAA currently has a vaccination program for morbillivirus, this disease is difficult to treat or prevent in Hawaiian monk seals.

While toxoplasmosis is responsible for most disease-related deaths in Hawaiian monk seals, several other diseases, including distemper virus (morbillivirus), West Nile virus, and leptospirosis threaten them [1]. Morbillivirus can be spread from domestic dogs to monk seals via bite wounds, so keeping dogs on leashes can help prevent the spread of this disease [5]. Although NOAA currently has a vaccination program for morbillivirus, this disease is difficult to treat or prevent in Hawaiian monk seals.

Learn more about morbillivirus and the vaccination program.

Fishing Gear and Debris Entanglement

Derelict and discarded fishing gear and marine debris pose a significant threat to Hawaiian monk seals, as hooking and entanglements can cause injury, loss of critical function, or even death. Hawaiian monk seals are known to become entangled in marine debris more than any other pinniped species. In the MHI, these interactions can occur when seals try to feed off the line of active anglers or when nets, lines, hooks, and other gear are left or discarded in the water where the seals can accidentally come into contact. If there is an animal entangled in debris, please immediately call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline 1-888-256-9840. Please call 833-4-Da-Nets to report marine debris sighted on the shoreline that are too large to remove yourself. Or report marine debris in Hawai‘i via DLNR’s marine debris reporting form.

Male aggression

One cause of Hawaiian monk seal decline, especially during the 1980s and early 1990s was due to male aggression [1]. This aggression can lead to severe wounds and death. There are two main types of male aggression that are relatively common. The first is groups of males mobbing other male and female seals. This aggression is likely due to a skewed sex ratio of more males than females in the monk seal population. The second is males attacking recently weaned pups. It has been attributed to numerous deaths of both male and female juvenile seals, particularly in the NWHI, which poses severe consequences to the recovery of the species when young, healthy, or reproductively viable seals are removed from the population.

Habitat Loss

Much of their habitat in the NWHI is subject to beach area loss due to sea-level rise and storm erosion. Losing these essential pupping sites may threaten the overall species’ recovery. Hurricanes such as Hurricane Walaka in 2018 have already decimated much of the French Frigate Shoals, where monk seals are known to reside and give birth. Additionally, new infrastructure and increased human traffic on pupping beaches in the MHI may disturb or inhibit successful birthing and nursing processes.

Harassment and Intentional killings

Intentional harassment has been reported numerous times on all main Hawaiian Islands, including touching, slapping, feeding, swimming near, or disturbing Hawaiian monk seals. This disturbs the monk seals while they are resting or looking for food and puts people in danger as well. If you encounter a Hawaiian monk seal, it is recommended to keep a distance of at least 50 feet, or 150 feet for mothers with pups. Mother monk seals can be very protective of their pups- do not approach them or go in the water near the mom and/or the pup.

Although rare, intentional killing of Hawaiian monk seals has occurred in the MHI, with four fatalities attributed to apparent gunshot wounds (as of 2018), and eight to blunt force trauma [1]. Care of and respect towards Hawaiian monk seals is important to help recover this species.

If you see any suspicious behavior, please call DLNR, Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement (DOCARE) statewide hotline at 1-643-DLNR (3567), or you can call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Hawaiian Monk Seal Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What Should I Do If I See a Hawaiian Monk Seal?

A. Consider the following:

- Is it hurt, or is it just resting? Most monk seals you see lying on land are perfectly fine and healthy, even if they’re lying very still. Biologists call this behavior “hauling out,” meaning the seal is resting and should remain undisturbed. Seals may also have mucus around their eyes or scars on their body, but this is also normal and nothing to be concerned about. Seals that look “splotchy” may just be molting- the natural process of shedding one layer of fur and growing a new one. However, if you see any obvious sign of injuries, such as an open wound or entanglement in rope or net, or are unsure about its health, please call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline immediately at 1-888-256-9840.

- Give them space. When you see a monk seal, the best thing to do is to remain quiet and give them space, as these animals may become protective or aggressive if you get too close. Also, because they are protected by the ESA, intentionally harassing, disturbing, or injuring a seal can result in significant fines or even time in jail. Current federal guideline for a safe public viewing distance of monk seals is 50 ft. A good test is to use the “Rule of Thumb.” To do this, stick your arm before you and give a thumbs up. If you can close one eye and the monk seal is covered by your thumb, you are far enough away.

- Keep dogs on a leash. Dogs can be threatened by or aggressive towards monk seals, and even if your dog is typically friendly and obedient, they may try to bite or attack a Hawaiian monk seal. Not only could this injure the seal or spread deadly diseases such as morbillivirus, but it may also put your dog in grave danger as monk seals have robust teeth and strong jaws. Anytime you are at the beach, your dog should be kept on a leash for your pet’s safety, and the seal’s!

- Report it! Anytime you see a Hawaiian monk seal, even if it’s healthy, it’s a good idea to report it. Scientists use this sighting information to learn more about the behaviors, population status, and health of the animals, so you would be helping to protect this very endangered species. If the animal looks healthy, call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840 and tell them about the seal you saw. Did you see any tags? What was it doing? Where was it?

If the animal looks in distress, is entangled or hooked, or has any other apparent injury, always report it immediately to the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840 and keep your distance for your safety. Injured, sick, or entangled animals can be unpredictable and dangerous. You can also report it to the marine animal stranding website.

Q. There’s a monk seal on the beach, and it looks sick – what should I do?

A. Most seals that haul out on the shoreline are just fine. They may have mucus around their eyes, scars on their body, and may lie very still as if they are not breathing, but that’s normal. Please keep your distance; do not get close to the animal. They need to be allowed to rest undisturbed. If you see an obvious sign of injuries, such as an open wound or entanglement in a rope or net, please call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

Q. What should I do if I see a marine mammal entangled in a rope or net?

A. Call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840. If it’s safe, please stay near the animal to keep track of it until a trained response team can arrive. Never try to untangle a marine mammal on your own without federal permission and guidance. Too many well-meaning people have been seriously injured or drowned while attempting to save an entangled marine mammal.

Q. What should I do if I accidentally hook a monk seal while fishing or if I see a hooked seal?

A. Please immediately call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840. You will then be given guidance over the phone on what to do, depending on the situation. Review the fisheries interaction guidelines for more information on how to avoid seal interactions. If, for some reason, you can not call, cut the line as close to the seal as SAFELY as possible. Do not injure yourself or those around you if you have accidentally hooked a seal—the less fishing line left on the seal, the higher chance that seal has of survival. Also, try fishing with barbless hooks! To learn more and receive free hooks, check out Fishing Around Protected Species.

Q. Why should we protect Hawaiian monk seals?

A. Hawaiian monk seals are native to the Hawaiian Islands and occur nowhere else. Though most monk seals are currently in the NWHI, rare sightings were recorded in the MHI in the early 20th century (beginning in 1928), and there is good archaeological evidence that monk seals were here hundreds of years ago. Seals usually feed on bottom-dwelling creatures, such as eels, flatfish, wrasses, octopus, and crustaceans. Seals have never been observed hunting pelagic fish, such as mahi-mahi, ahi, aku, etc. Like sharks and other marine predators, seals play an essential role in our reef ecosystem, maintaining a balance that allows for the highest productivity levels in our local fisheries.

Q. How can I help protect Hawaiian Monk seals?

A. Here are some of the best ways you can help monk seals in your everyday life:

- If you see them, respect their space.

- Report any sightings or injuries to the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline at 1-888-256-9840.

- Keep all cats indoors and do not feed stray cats (Toxoplasmosis).

- Keep your dogs on a leash whenever you are near the ocean.

- Clean up your trash and keep the beaches clean and free of debris.

- Report marine debris: (833) 4-Da-Nets (833-432-6387), or utilize the state-wide marine debris reporting form.

- Use pono fishing practices- avoid snagging line on rocks and reefs and do not leave a fishing line in the water; clean up hooks, lead, and lines and discard them properly; pull up lines whenever you see a seal, and never feed the seals or try to interact with them.

- Volunteer with a monitoring and conservation program such as:

The Marine Mammal Center, Ke Kai Ola, Hawaiʻi Island and Maui

Hawai‘i Marine Wildlife Response, O’ahu and Moloka’i

Kaua‘i Conservation Hui: email [email protected] or call (808) 651-7668

Q. How close can I get to whales, dolphins, and monk seals?

A. There are several rules when it comes to viewing marine mammals.

- Humpback whales: The required viewing distance is at least 100 yards away. Federal law prohibits approach within 100 yards, including by boat, kayak, drone, when swimming, or by any other vessel or means

- Spinner Dolphins: Federal law prohibits swimming with, approaching, or remaining within 50 yards of spinner dolphins in Hawai‘i.

- Hawaiian Monk Seals: Recommended viewing distance: At least 50 feet (15 meters) away—on land and in water. Take special care around mothers and pups; for your safety, do not swim near the mother and pup. Several people have been bitten and severely injured by the protective mother monk seal even when snorkeling far away. DO NOT go in the water near the mom and pup. View mother seals and their pups from at least 150 feet (about 45 meters) away and stay behind any signs or barriers.

- The recommended viewing distance for all other dolphins and small whales (including false killer whales) is at least 50 yards (45 meters) away. Getting close to these animals may constitute a federal or state violation if the animal is disturbed or if your action has the potential to disturb its natural behavioral patterns. Federal and state recommendations, for your safety and the animals’ protection, include that everyone should stay at least 50 yards from all marine mammals. If maintaining this distance isn’t possible, keep safety in mind and move away from the animal as carefully as possible, avoiding sudden movements and other actions that might disturb the animal. For wildlife viewers, please enjoy from a distance – use binoculars and telephoto lenses to get the best views without disturbing the wildlife.

Q. Can a drone film whales, dolphins, and monk seals?

A. Adhering to NOAA guidelines: The noise and the proximity of drones can disturb marine wildlife. When viewing marine mammals from the air using a drone:

- Maintain a 1,000-foot minimum altitude when viewing marine mammals from the air in a human-crewed aircraft (e.g., helicopters, airplanes). Federal law requires aircraft to fly no lower than 1,000 feet above humpback whales in Hawai‘i and 1,500 feet above North Atlantic right whales throughout U.S. waters.

- Avoid buzzing, hovering, landing, taking off, or taxiing near marine mammals (on land or in the water), as these actions may alter animal behavior.

- Avoid flying drones or unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) near animals. The noise and the close proximity of drones can harass the animals and cause stress.

A note on drone/UAS guidance: NOAA Fisheries is currently developing national guidance for drone (or UAS) operations targeting marine mammals and sea turtles. Until then, dolphins, whales, seals, and sea lions are protected species, and harming or disturbing them can violate federal law.

Literature Cited

- NOAA Fisheries. Hawaiian monk seal.

- Wilson, K., C. Littnan, P. Halpin ,and A. Read. 2017. Integrating multiple technologies to understand the foraging behavior of Hawaiian monk seals. Royal Society Open Science. 4 (3): 1-14.

- Parrish, F.A., G.J. Marshall, B. Buhleier, and G.A. Antonelis. 2008. Foraging interaction between monk seals and large predatory fish in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Endangered Species Research. 4:299-308.

- NOAA Fisheries. A cat-borne threat to Monk Seals.

- NOAA Fisheries. Conserving Hawaiian Monk Seals Through Protections and Vaccinations.