9/12/24 – Fighting back against invasive algae

The issue of marine debris is a great concern for the Hawaiian Islands. Fishing nets, plastic particles, and various metals washed in from the ocean have become a common sight at beaches throughout the State and are now significant in numerous ecological and cultural coastal areas. To combat this, various non-profit organizations have made cleanup projects a part of their focus, helping to engage local communities while providing a necessary service to make the islands a cleaner place. One such organization, Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP), focuses on large-scale marine debris removal missions in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, located within the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. The monument is one of the world’s largest protected areas and is well known for its cultural and natural values.

The removal of marine debris from the monument does come with a series of challenges. Difficult ocean conditions, transportation of large quantities of debris out of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, and disposal of the debris are all things that PMDP must consider when putting together a successful field operation in such a remote location. For the Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) team, the biggest consideration when thinking about debris removal is the accidental transport and introduction of non-native and invasive species to the main Hawaiian Islands. In the open ocean, the lack of hard surfaces leads animals to cling to whatever objects they can find. The slow build-up of these organisms on nets, driftwood, broken pieces of marine vessels, or any other hard floating substance is a process known as biofouling. As debris is circulated by ocean currents, organisms from various locations can glom onto these materials, which can then wash up on the beaches of the Northwestern and Main Hawaiian Islands. Hawaiʻi already has the highest number of non-native aquatic species of any of the fifty U.S. states, and introducing more will only put further pressure on Hawaii’s vulnerable native and endemic species.

PDMP crew members work to remove marine debris from the monument. Photo: James Morioka

Chondria tumulosa

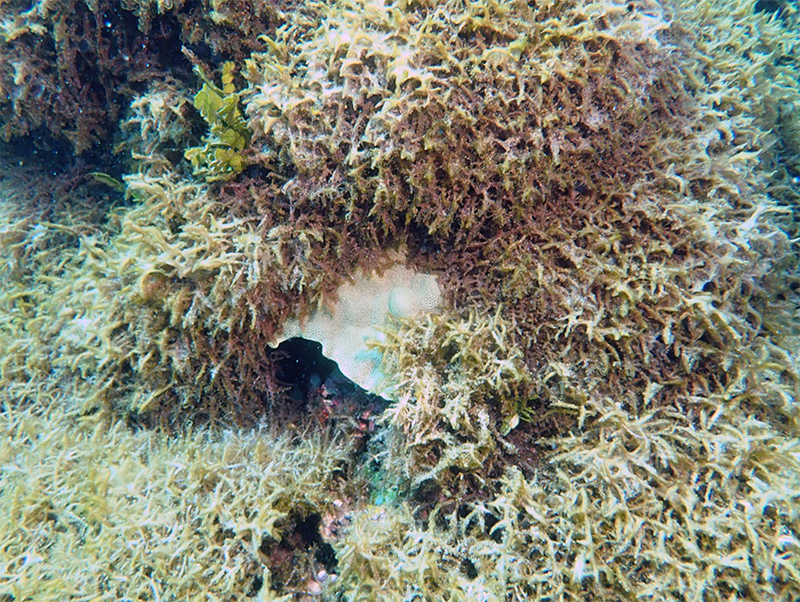

Unfortunately, a species of potentially invasive algae has recently been identified in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Discovered in 2016, an algae known as Chondria tumulosa has sprung up from small amounts at Manawai to large populations at Kuaihelani and Hōlanikū. This has caused massive damage to the ecosystem of the northwestern atolls, covering up hundreds of acres of reef and smothering vast swaths of coral colonies. Currently, not much is known about C. tumulosa, such as where it originated from or how it was introduced. Without knowing the source of this cryptogenic species, the current focus is on using all available resources to prevent it from spreading further in the Northwestern islands and from reaching the main Hawaiian Islands, as once an invasive species becomes established, eradication is nearly impossible.

Chondria tumulosa overgrowing a coral skeleton. Photo: Taylor Williams/University of Hawai‘i

Testing the Spread

In order to put together a comprehensive plan to contain this new species, more information was and still is needed. A joint collaboration of federal, state, and private partners created a plan to test Chondria’s ability to spread to the main Hawaiian Islands via marine debris removed from the monument. Currently, PMDP mitigates this issue by avoiding removing debris from areas with C. tumulosa growth and, when the debris is removed, thoroughly bleaching all of the material to ensure that no invasives are accidentally picked up and brought back alive to Oʻahu. However, this is dangerous for the crew, as the sloshing of large amounts of bleach in containers mid-journey creates a potential chemical hazard to those working on the boats.

Seeking a safer method to mitigate the spread of C. tumulosa, researchers began investigating whether desiccation would sufficiently dry out and kill any algae during the five-day journey from the monument to Oʻahu. To test whether the algae will die off within this time frame, the DAR AIS team and other collaborators experimented to mimic the conditions on the ship transporting marine debris from Papahānaumokuākea. Because of the threat of Chondria escaping on Oʻahu and becoming established, another invasive algae that is closely related to C. tumulosa,Acanthophora spicifera, was used as a test subject. Since A. spicifera is already established here on Oʻahu, protective protocols are already in place to help mitigate any additional spread, making it easier to work with than C. tumulosa. The alga was placed into several sets of bins for either five days, fourteen days, or thirty days in order to test various desiccation timelines. Each of these bins contained tightly packed marine debris as would commonly be seen during removal operations in the monument. Two types of containers were set up for the test: a completely sealed container mimicking what is currently on the ship and a container with ventilation holes cut in it. This second container type would see whether ventilation would aid in the desiccation of the removed marine debris. If modifications need to be made to the current transportation method, testing additional container types would help provide information on the best operating procedures.

The team used a pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometer to check whether the algae kept inside the containers had completely died off. PAM fluorometry involves shooting a very focused beam of light at a plant and recording how much photosynthesis occurs as the plant absorbs the light. By comparing the photosynthesis levels from algae before they were placed into the bins to photosynthesis levels after the algae were removed from the bins, researchers can track the trajectory of the health of the plant. Currently, experiments are still ongoing and will be wrapping up in the fall of this year. Information gathered from these trials will be used to make informed decisions about the best way to prevent C. tumulosa from spreading to the main Hawaiian islands. Because of the concern associated with the spread of this new invasive, tests focused on finding absolutely zero signs of life after desiccation. Initial results seemed to show that longer desiccation periods would probably be necessary to entirely kill off any remaining C. tumulosa in collected marine debris.