Whales and Dolphins

Whales: Three important species in Hawaiian waters

Whales are in the order Cetacea, divided into two suborders: Odontoceti and Mysticeti. Whales in the suborder Odontoceti have teeth. Whales in the suborder Mysteceti have baleen plates and filter feed. Dolphins and porpoises are also cetaceans, in the order Odontoceti.

Odontocetes (toothed whales and dolphins)

Unlike mysticetes, odontocetes all have teeth of some kind inside their jaws. The teeth size, number, structure, and function vary considerably among each species. Not all odontocetes are believed to use their teeth for feeding and may use them for showmanship or aggression.

Another key identifier of odontocetes from mysticetes is that they have one blow-hole on the top of their head, and mysticetes have two. When odontocetes come to the surface to breathe, you will see a vertical tower of mist created by the upward spray of the water resting on the surface of their blowhole when they exhale. Whereas, baleen whale “blows” will create a “V” formation (called a plume).

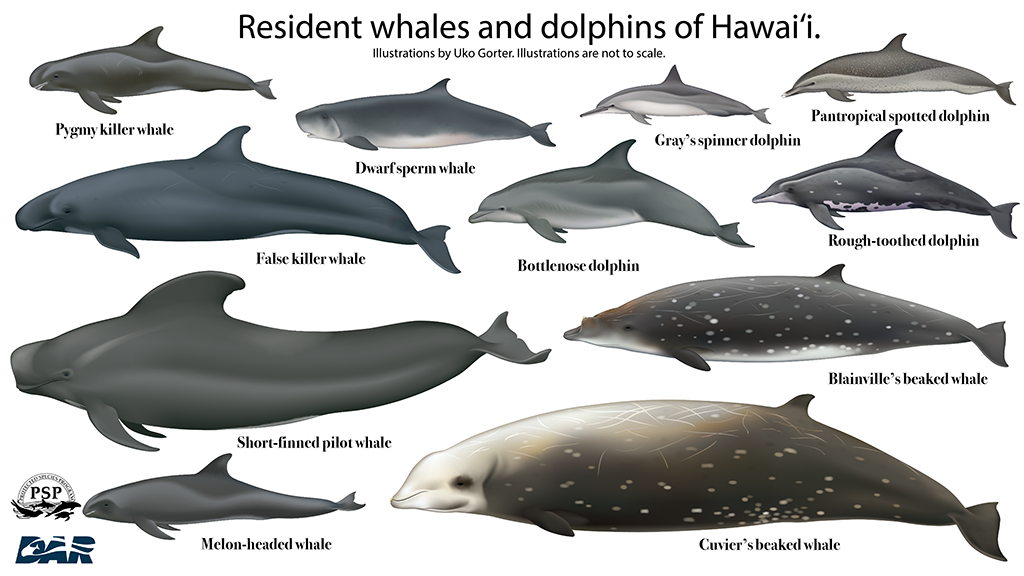

Odontocetes in Hawai‘i

Eighteen species of toothed whales can be found year-round in Hawaiian Waters. Of the 18, only two

are listed as threatened or endangered under the

Endangered Species Act: the insular Main Hawaiian

Islands population of the false killer whale (Pseudorca

crassidens) and the sperm whale (Physeter

macrocephalus). Read on for more information on these two species.

False Killer Whale

Hawaiian name: ka palaoa

Scientific name: Pseudorca crassidens

Description and Natural History

Contrary to its common name, the false killer whale (FKW) is not directly related to the killer whale (Orcinus orca). They were named false killer whales due to perceived similarities between the skulls of the two species. False killer whales are often referred to as “blackfish” by commercial fishers, along with similar-looking species such as the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata), melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra), and the short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus). Their Hawaiian name, palaoa, is the same as that used for other toothed whales; the Hawaiian and western classification of species are based on different criteria.

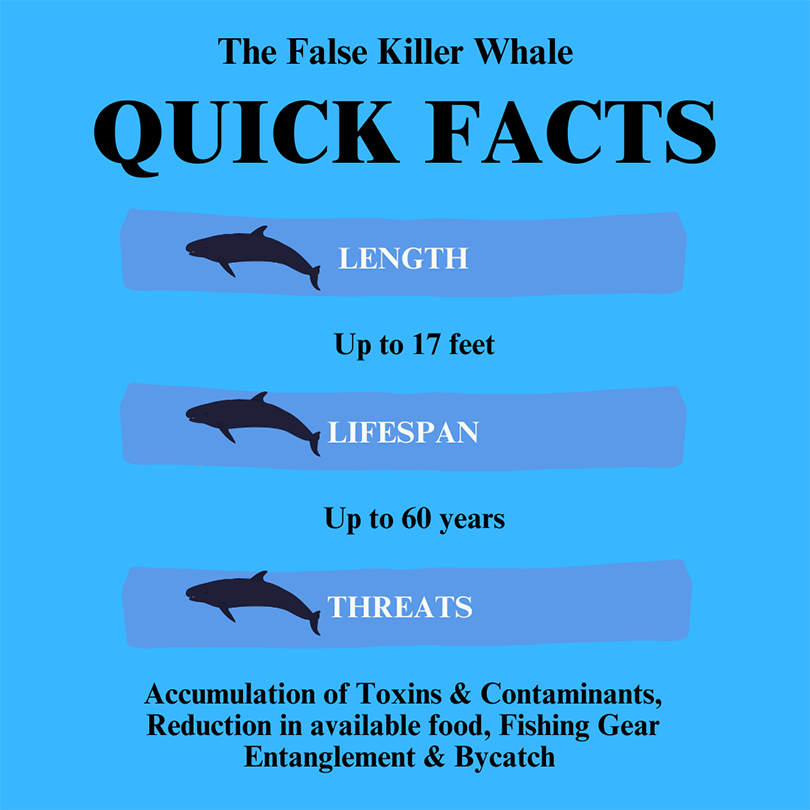

False killer whales can reach up to 17 feet in length or more when fully grown and live to be over 60 years old. False killer whales are top predators, reproduce very slowly, and are rare. A 2017 study found that false killer whales were the least abundant of the 18 species of toothed whales and dolphins in Hawaiian waters out to the international boundary [1].

Populations

The same 2017 study [1] reported there are three false killer whale populations in Hawaiʻi: the northwestern Hawaiian islands population, the pelagic population roaming in waters outside the main Hawaiian islands (MHI), and the endangered “insular” population, which confines itself to waters within the MHI. The MHI insular population is the smallest, consisting of approximately 140 whales. Dr. Robin Baird of Cascadia Research Collective, determined that the MHI insular population is composed of long-term residents genetically different from other Pseudorca, making them unique to Hawaiian waters [2].

The MHI insular population is estimated to be half the size that it was in 1980. Aerial surveys undertaken from 1993 through 2003 by Joe Mobley of the University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu showed a steep decline in FKW sighting rates [3]. Population surveys since the 1990s by Dr. Baird and his colleagues indicate that the MHI insular population has continued to decline dramatically [4]. In 2023, Dr. Janelle Badger of NOAA’s Pacific Island Fisheries Science Center, Dr. Baird and their colleagues estimated the MHI population was declining by 5% per year.

Status and Protection

Due to its small population size, low reproductive rate, and continuing decline, the MHI insular “distinct population segment” was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in November 2012. The endangered insular population is protected federally by both the ESA and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), and locally by the Hawai’i Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 195D and Hawaii Administrative Rules (HAR) 13-124. The entire species was listed as “near threatened” on the The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species in 2018. All the FKW populations are federally protected by the MMPA.

Diet and Habitat

Dr. Baird affirms false killer whales are highly social species that form long-term associations with one another [2]. They eat fish commonly caught and consumed by humans, such as ahi (tuna), ono (wahoo) and kajiki (swordfish or marlin). They frequently share food, often saving the best parts of the fish for the oldest individuals. Older group members pass on cultural information to younger generations and help raise the calves [1].

Reproduction

False killer whales mature slowly, reproduce infrequently, and are long-lived [1]. Males reach sexual maturity around ten years, and females much later at 18 years. Females give birth to a single calf every six to seven years and go into menopause in their 40s. The average life span is 58 years for males and 62 for females.

Threats – Fisheries Interactions

False killer whales are known to depredate catch (take fish and bait off a line) as they pursue the same fishes preferred by humans. This depredation has been documented since the 1960’s. Photo analysis by Dr. Baird and colleagues found that out of 73 insular FKW with good quality head photographs, 23% had mouth scarring consistent with hook and line interactions [5]. Of 165 insular FKW with good quality dorsal fin photos, 9% had dorsal fin lacerations consistent with fishing line injuries. We do not know how often these fishery interactions are fatal.

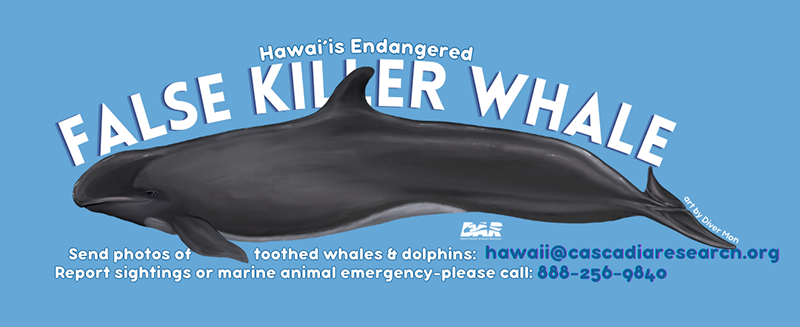

Your help is requested to report sightings and interactions with false killer whales to increase our knowledge about their populations. Any photos or locations of sightings are helpful!

PLEASE: Report False Killer Whale Sightings interactions by emailing photos and videos to [email protected]. Or call: 1 (888) 256-9840 option #5, so we may learn more about how the population is doing and how to release a whale best if the fishing gear is attached.

See how to tell the difference between resident whales in Hawai‘i.

Check out a video about the False Killer Whale, presented by the PSP program:

If you see an injured or entangled whale in Hawaiian waters please call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife hotline at 1-888-256-9840 (Option 3). To learn more about the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary and Large Whale Entanglement Response program, click here.

Sperm Whale

Sperm Whale

Hawaiian name: ka palaoa

Scientific name: Physeter macrocephalus

Description and Natural History

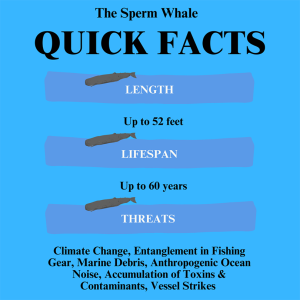

Sperm whales are the largest of all toothed whales (Odontoceti). Adult males can grow up to 52 feet in length and weigh up to 80 tons.

Their massive heads and rounded foreheads make it easy to identify sperm whales, and they have the largest brain of any creature known to have lived on Earth [6]. Their heads also hold large quantities of spermaceti, a waxy substance which helps sperm whales focus on sound. Their Latin name, “macrocephalus” refers to their large heads.

Mature males are typically 30% to 50% longer and three times as massive as females. They are believed to live up to 60 years or more.

Sperm whales were whaled (hunted) in Hawaiian waters between 1800 and 1987. More than 300,000 sperm whales are estimated to have been killed off of Hawaiian shores during that time. Sperm whales were hunted for oil, blubber, ivory (in their teeth), spermaceti (for use in oil lamps, lubricants, and candles), and ambergris. Ambergris, or “gray amber,” is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull gray or blackish color produced in the digestive system. It was used for lanterns and perfume. Sperm whales were easy to harpoon because they were curious about ships and would approach whaling vessels to their demise.

Deceased sperm whales sometimes wash up on Hawaiian beaches. Before western contact, extremely sacred lei, or necklaces, were made out of a sperm whale tooth (niho palaoa) and braided human hair. The lei niho palaoa was reserved for the ali’i (royalty). It symbolized a chief’s rank and authority. Joylynn Olivera explains that the significant tongue shape of the niho palaoa indicated “that the chief was someone who spoke with authority and took charge of the community” [7]. A lei niho palaoa is one of the most prized cultural artifacts of the Hawaiian people to this day.

Status and Protection

Sperm whales are listed as endangered under the ESA. They are also federally protected by the MMPA. If sperm whales are found within three nautical miles of the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI), they are also protected by Hawai’i Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 195D and Hawaii Administrative Rules (HAR) 13-124. They are also listed as vulnerable under the IUCN Red List.

The best available population estimate for the sperm whales in Hawai‘i is from a 2010 shipboard line-transect survey by Dr. Amanda Bradford and her colleagues in an area 200 miles from both the main Hawaiian islands and the northwestern Hawaiian islands (in the Hawai‘i Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ) [4]. The survey estimated an abundance of about 5,000 sperm whales within the Hawai‘i EEZ.

Diet and Habitat

Sperm whales are the world’s largest odontocetes and hunting predator. They prey on squid and fish. They forage deeply, up to 6,561 ft (2 km) in depth. Sperm whales can stay down for up to 45 minutes with surface intervals of nine minutes, which makes them hard to follow and study.

Reproduction

Like most large whale species, courting rituals are fierce. Males battle for mating rights to breed with multiple females. Sperm whales mature slowly and reproduce infrequently; female sperm whales reach sexual maturity around eight to ten years and produce one calf approximately every five to seven years. Female sperm whales mate once every four to 20 years until about 40. With sperm whales, birth is a very social event. The sperm whale pod will gather and form a protective circle around the mother giving birth.

Threats

Like most cetacean species, sperm whales face many human-caused threats, including entanglement, vessel strikes, acoustic disturbance, habitat degradation, marine debris, and environmental changes affecting food resources.

If you see an injured or entangled whale in Hawaiian waters please call the

24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife hotline at 1-888-256-9840 (Option 3)

Mysticetes (baleen whales)

Mysticetes do not have individual teeth like other mammals. Instead, they have large baleen plates made of keratin – the same thing that makes up human hair and nails! The baleen plates hang down from the whale’s upper jaw. They use these baleen plates to filter food from the water – hence the term “filter feeders.” To do this, they open their mouths widely to allow large gulps of water containing prey, like krill or small fish. Then they partially shut their mouths, press their tongue against the roof of their mouths, and force the water out through their baleen, keeping all the prey inside to swallow!

Another key identifier of mysticetes is that they have two blow-holes on the top of their head, unlike odontocetes, which only have one. When they come to the surface to breathe, you will see a plume of water when they exhale. Their plumes are easily differentiated because the baleen whales have a plume that creates a V formation (almost like a heart). In contrast, odontocetes will blow a vertical tower of mist.

Mysticetes in Hawai‘i

There are 16 types of baleen whales on Earth; eight of these whales have been observed in Hawai‘i: the humpback whale, sei whale, fin whale, minke whale, blue whale, Bryde’s whale, North Pacific right whale, and gray whale. The humpback whale is the most famous baleen whale in Hawaiian waters.

Humpback Whale

Hawaiian name: ka koholā

Scientific name: Megaptera novaeangliae

Description and Natural History

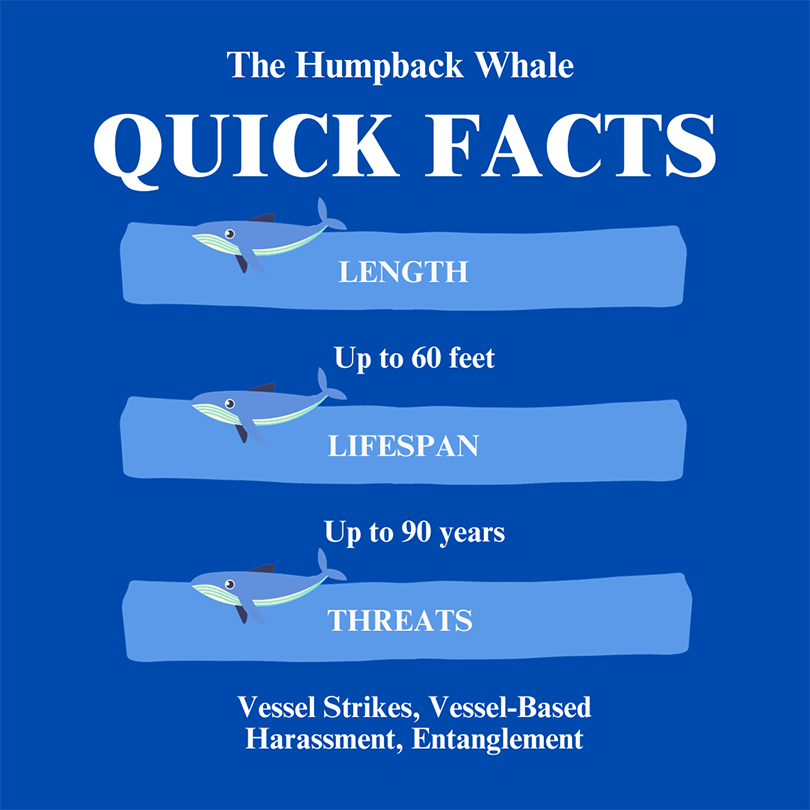

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is the most common baleen species in Hawaiian waters. They are large mammals that can live up to 90 years of age and average anywhere from 45-60 ft and 66,000 lbs when fully grown, roughly the size of a school bus.

Found all over the world, humpbacks are divided into 14 Distinct Population Segments (DPS): populations of whales that are genetically and geographically distinct. The humpbacks in Hawai‘i – the Hawaiʻi DPS – migrate annually from Alaska and the Bering Sea to Hawaiʻi, making the 3,000-mile trip to mate, give birth, and nurse their calves in the warm, shallow waters of the Hawaiian islands. Before 2015, counts and surveys estimated as many as 10,000 humpbacks in this DPS. However, in 2016, the number of humpbacks returning to Hawai‘i plummeted drastically. Dr. Marc Lammers of the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary (HIHWNMS) and Dr. Rachel Cartwright of California State University, Channel Islands, estimated that the numbers of whales returning to Hawaii dropped by at least half and there were significantly fewer calves. In 2016, three ocean warming events: an El Niño, a Pacific Decadal Oscillation, and a marine heatwave contributed to the warming of the Pacific Ocean. It is most likely that numbers of migrating whales dropped due to the diminished availability of humpback whale food sources, such as krill and small fishes. The numbers have rebounded but annual surveys by HIHWNMS staff indicate that it may be too soon to say that numbers have returned to pre-2016 levels [8].

Status and Protection

Like all marine mammals, all humpback whale DPS are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). The global population of humpback whales was initially listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). However, after years of research, in 2016, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) divided the species into 14 DPS, and delisted all but four. Two DPS that use US waters, Central America and Western North Pacific DPS, remain listed as endangered under the ESA, and one DPS in US waters (Mexico DPS) remains listed as threatened. There are other endangered DPS in foreign waters. The Hawai‘i DPS is not listed. The International Union for Conservation Nature (IUCN) lists the global population of humpbacks as least concern.

Diet and Habitat

Diet and Habitat

Humpback whales are filter feeders and rely on small fish and zooplankton, such as krill, to make up their large diet. When humpbacks are in Hawai’i, they do not eat much because these food sources are not abundant in Hawaii’s low-nutrient waters. A 2018 Humpback whales rely on metabolizing their body fat while in Hawai’i [9]. Thus, they must return to Alaska to feed, once the calves are big and strong enough to make the long journey home.

Reproduction

The Hawaiian Islands, particularly the shallow waters around the islands of Maui County, make an excellent place for mating, birthing, and nursing. The warm waters of Hawaiʻi are safe from orca predation and help the calves stay warm while they nurse and form the blubber they need to survive Alaska’s cold water temperatures. Females will produce one calf every two to three years on average; however, annual calving does occur. The mother will stick very close to the calf for the first year, providing the thick, fatty milk that the calf requires.

Behaviors

Humpback whales are known to be an active and acrobatic species putting on quite a show in Hawaiian waters. Various behaviors, such as breaching, spy hopping, tail slaps, peduncle throwing, and pectoral fin slaps, are observed daily during whale season. Although scientists are still unsure of the primary reason for these behaviors, they are thought to be related to male competition, maternal protection, communication, curiosity, and play.

Threats

Although the Hawai’i DPS of humpback whales have experienced a significant recovery, they still face many human-caused threats, including marine debris entanglement, vessel strikes, and environmental changes.

Ed Lyman of the HIHWNMS studies humpback whale entanglements and leads the Pacific region’s Large Whale Entanglement Network. Together with his colleagues Maria Harvey and Rachel Finn, his research shows that about 20% of humpback whales show scarring from entanglements. Additionally, every year, Lyman and a trained team respond to reports of humpback whales entangled in fishing nets, buoys, crab pots, or boat moorings – even undersea cable [10]. Roughly two thirds of the entangled whales seen in Hawai ‘i have brought the gear down with them from the north; the rest are entangled locally. Entangled humpbacks can starve, drown due to restricted movement, or suffer systemic infections that further compromise its health.

Humpback whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in coastal areas with heavier ship traffic [9]. Hawai’i is dependent on vessel traffic for many forms of commerce, although Hawai‘i is fortunate in that most of the vessels are small. Regardless, every year, the HIHWNMS reports that humpback whales are struck by boats, especially calves which surface more frequently than adults. In Hawai‘i, DLNR’S DAR and Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation (DOBAR), the HIHWNMS, NOAA Fisheries, and the Pacific Whale Foundation (PWF) worked with members of the commercial tour industry to amend long-standing best management practices (BMPs) around whales. These new recommendations are meant to reduce boat strikes and keep both people and whales safe.

Best Management Practices Around Humpback Whales by NOAA Fisheries

Major recommendations in the existing species-wide recovery plan are:

- Reduce or eliminate injury and mortality caused by fisheries, fishing gear, and vessel collisions

- Minimize effects of vessel disturbances

- Continue the international moratorium on commercial whaling

- Collect as much data as possible from dead whales through our Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Program

Efforts to implement recovery for humpback whales include:

- Creating marine protected areas for humpback whales

- Minimizing vessel disturbances

- Reducing entanglement in fishing gear

- Reducing vessel strikes

- Understanding and addressing the effects of ocean noise

- Collaborating with the Commission on Environmental Cooperation to develop the North America Humpback Whale Conservation Action Plan for the United States, Canada, and Mexico

Efforts to minimize whale watching harassment include:

- Restrict approaching within 100 yards of a humpback whale

- Avoid placing your vessel in the path of oncoming humpback whales, causing them to surface within 100 yards of your vessel

- Not disrupting the normal behavior or prior activity of a humpback whale

- Operating your vessel at a slow, safe speed when near humpbacks

Efforts to reduce vessel strikes include:

- Requiring vessels to slow down in specific areas during specific times (Seasonal Management Areas)

- Advocating for voluntary speed reductions in Dynamic Management Areas

- Recommending alternative shipping routes and areas to avoid

- Modifying international shipping lanes

- Developing mandatory vessel reporting systems

- Increasing outreach and education

- Improving our stranding response

To report a violation of approach guidelines and regulations, call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline: 800-853-1964.

IT’S THE LAW!

If you see a humpback, you and/or your vessel should stay more than

100 yards away for you and the marine animal’s protection.

To report a violation of approach guidelines and regulations,

call the Enforcement Hotline: 800-853-1964.

If you see an injured or entangled whale in Hawaiian waters

please call the 24-hour NOAA Marine Wildlife hotline at 1-888-256-9840 (Option 3).

To learn more about the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National

Marine Sanctuary and Large Whale Entanglement Response program, click here.

Literature Cited

- NOAA Fisheries. (2017, June). False killer whales: Sentinels of ocean health.

- Baird, R.W., A.M. Gorgone, D.J. McSweeney, D.L. Webster, D.R. Salden, M.H. Deakos, A.D. Ligon, G.S. Schorr, J. Barlow and S.D. Mahaffy. 2008. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the main Hawaiian Islands: long-term site fidelity, inter-island movements, and association patterns. Marine Mammal Science 24:591-612.

- Reeves, R. R., Leatherwood, S., & Baird, R. W. (2009). Evidence of a possible decline since 1989 in false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) around the main Hawaiian Islands. Pacific Science, 63(2), 253–261.

- Bradford, A. L., Forney, K. A., Oleson, E. M., & Barlow, J. (2017). Abundance estimates of cetaceans from a line-transect survey within the U.S. hawaiian islands exclusive economic zone. Fishery Bulletin, 115(2), 129–142.

- Baird, R.W., S.D. Mahaffy, A.M. Gorgone, K.A. Beach, T. Cullins, D.J. McSweeney, D.S. Verbeck and D.L. Webster. 2017. Updated evidence of interactions between false killer whales and fisheries around the main Hawaiian Islands: assessment of mouthline and dorsal fin injuries. Document PSRG-2017-16 submitted to the Pacific Scientific Review Group.

- NOAA Fisheries. (2023, January). Sperm whale.

- Olivera, Joylynn. 2001. The Cultural Significance of Whales in Hawai‘i. Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, Kīhei, HI. 4 pp.

- Weinberg, Elizabeth. (2018, September). Humpback whales are navigating an ocean of change. Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

- US Department of Commerce, NOAA Fisheries. (2014, May). National marine sanctuaries. Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale 2010 Condition Report.

- Harvey, M., R. Finn, E. Lyman. Health and Risk Assessment Monitoring Program 2022-2023 Season-End Report. Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, Kĩhei, HI. 21 pp.