Our Work

Curbing the extinction of Hawaii’s rarest snail species is a daunting task to say the least but with hard work and dedication our methods have proven effective. Throughout the first few years of SEPPs existence our work was focused on predator control around and monitoring of wild populations. Within the past few years, however, we have witnessed the majority of rare snail populations plummet towards extinction due to predator incursions and climate change. Unfortunately, many of these species now only exist in captivity but our field team is working hard to prepare protected areas so these individuals can be released safely back into the wild. Through captive rearing, predator control, predator exclusion and reintroduction our beloved kāhuli will be around for future generations to marvel over.

Captive Rearing

The SEP program maintains a captive rearing program to encourage reproduction of Hawai‘i’s rare snails. This work is conducted in a controlled laboratory to provide snails with optimal, predator-free living conditions. The images below show some of our captive rearing resources and the snails that make use of our lab.

Predator Control

When predator load is high in an area, and snails are quickly disappearing, SEPP uses several control techniques to slow the rate of decline. Because predator control is not 100% effective, we consider these techniques as a stopgap that buys us some precious time.

The introduced rosy wolf snails and Jacksons chameleons are difficult to detect in the wild. SEPP and our partners must manually remove these in the forest by physically searching for them. As of yet, no effective baits or traps have been developed.

When it comes to rats, we are very good at reducing threats. SEPP uses a technique whereby 10-40 rat traps are spaced in a grid at 5-10 meter intervals, in and around a snail population. A high density of traps ensures rats have a high probability of encountering a trap before eating too many snails. SEPP uses two types of traps to control rats around snail populations. Kamate traps come from New Zealand and are of a traditional snap trap design, however they are made of stainless steel. Good Nature traps also come from New Zealand, and are capable of humanely dispatching up to 24 rats before the traps need to be reset. These traps are completely mechanical and rely on compressed CO2 cartridges to function.

Predator control has been the go to method for SEPP and partner organizations to protect wild populations. Unfortunately, within the past few years wild populations have been ravaged by the more insidious rosy wolf snail. These declines forced SEPP to concentrate efforts on captive rearing and reintroduction of snail populations within predator proof habitat.

Predator Exclusion

Over the past 20 years walled exclosure structures protecting small patches of habitat have been the most effective way to secure wild populations of Hawaiian terrestrial snails from the appetites of introduced invasive predators. The first iteration of these was built by the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources in partnership with the University of Hawaii in 1998. This structure featured a solid wall barrier with a trough of salt around the perimeter to prevent incursion by the rosy wolf snail (Euglandina rosea).

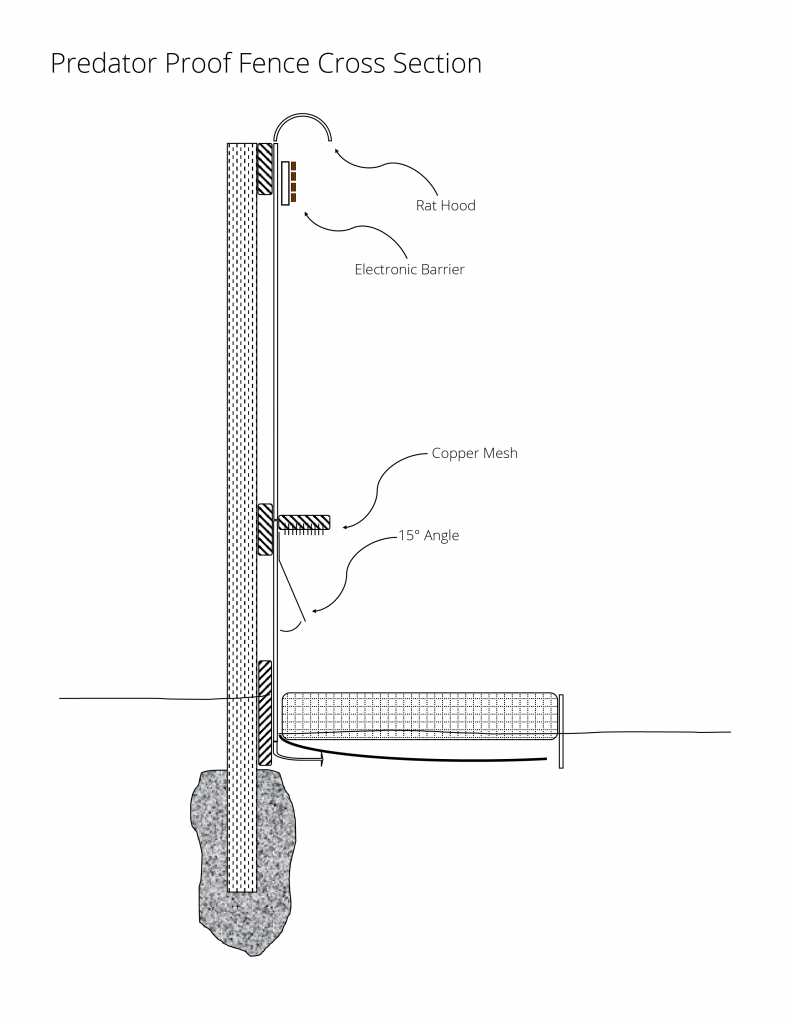

Over the years the barrier technology has improved and today a design created by the Oʻahu Army Natural Resources Program is used extensively. This design consists of a solid wall barrier with smooth sides, and a rolled hood at the top of the wall to prevent ingress by rodents and Jackson’s chameleons. Three additional barriers are installed around the perimeter to prevent ingress from the rosy wolf snail (Euglandina spp). These barriers consist of a 15° angled flange, rows of sharp cut copper wire mesh, and electrical wires. Rosy wolf snails have difficultly maneuvering under the angled flange and often get stuck. If they make it past, the rows of cut copper wire mesh are difficult for snails to cross, but if they get past this barrier, we electrocute them. The combination of these three barriers has proven to be very effective.

|

|

While walled exclosures structures are used to protect larger tracks of habitat, there are many situations where the geology and terrain of an area don’t allow for this type of construction. To accommodate different situations, the Snail Extinction Prevention Program has been developing other tools. These include using small cage structures to completely protect groups of breeding individuals. While not appropriate for all species, SEPP has successfully protected rare ground snails with this tool. A feature of the design is that small newborn snails of the target species can crawl through the wire mesh, while larger breeding adults cannot. This allows for a steady flow of juvenile snails into the surrounding habitat while breeding adults are protected, helping populations persist in their natural habitat.

Reintroduction

Once a population has grown robust enough in captivity, individuals are reintroduced to their proper habitat that has been cleared of any introduced predators through predator control and predator exclusion. Reintroducing these animals to the wild is perhaps one of the most rewarding activities and what our program works diligently towards achieving each and every day. However, the work does not stop here. We continue to closely monitor protected populations on a quarterly basis to ensure they remain safe and healthy.