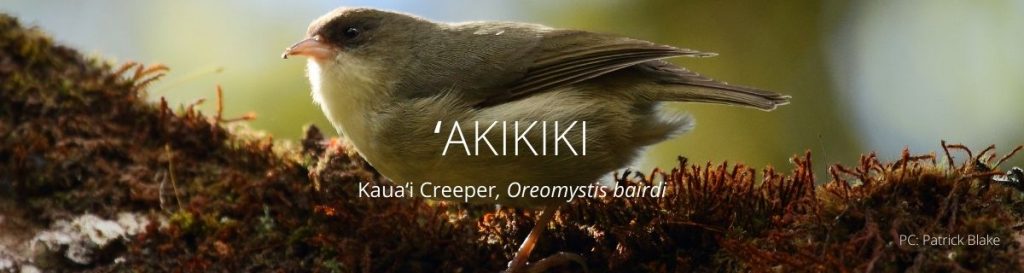

ʻAkikiki

Names

- Ōlelo Hawaiʻi: ‘Akikiki

- Common: Kauaʻi Creeper

- Scientific: Oreomystis bairdi

Song

Conservation Status

- Federally Listed as Endangered

- State Listed as Endangered

- State Recognized as Endemic

- NatureServe Heritage Rank G1—Critically Imperiled

- IUCN Red List Ranking—Critically Endangered

- Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds—USFWS 2006

Species Information

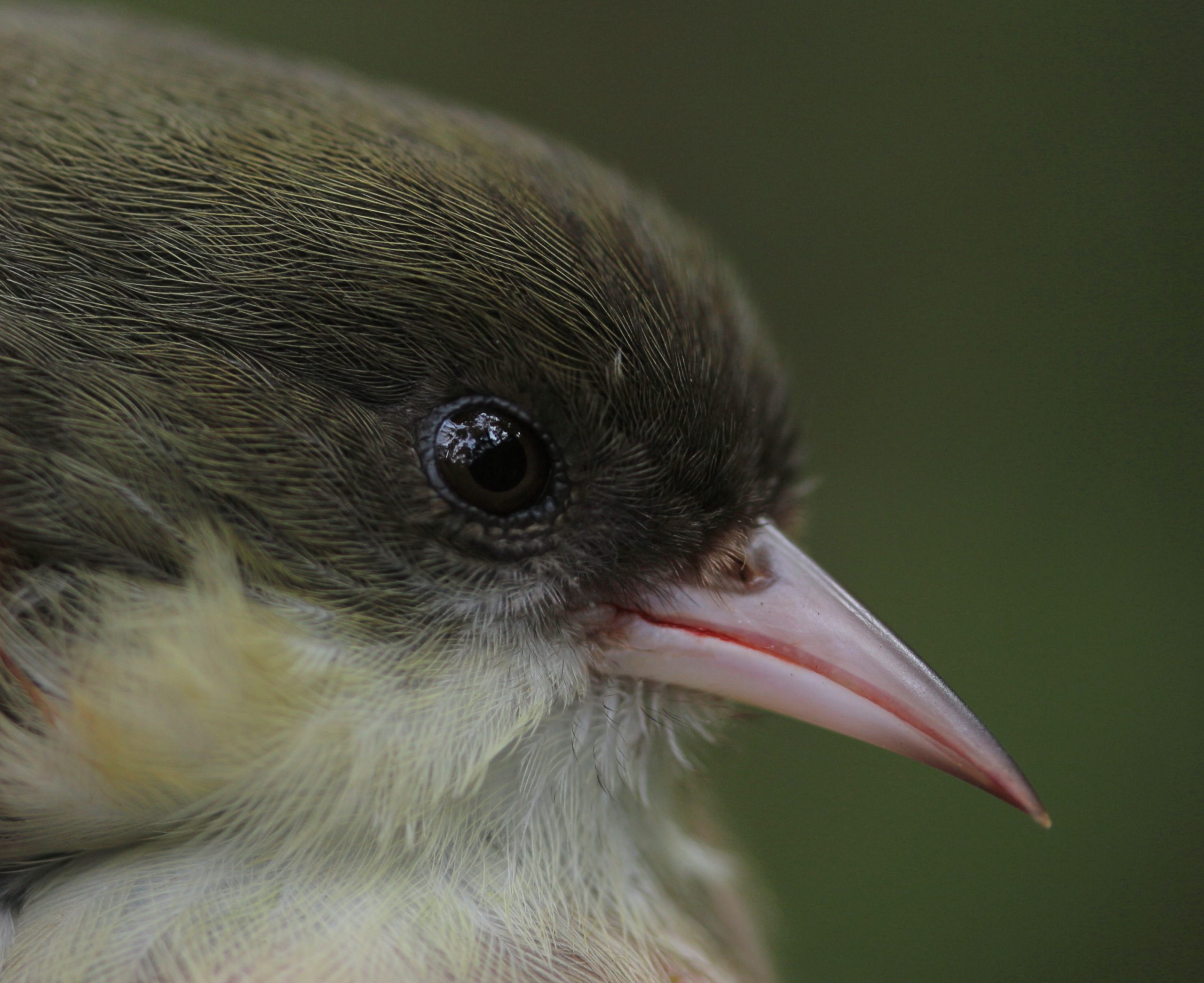

ʻAkikiki. PC: Justin Hite, KFBRP, UH PCSU

The ‘akikiki, or Kaua‘i creeper, is a small, drab Hawaiian honeycreeper (Family: Fringillidae) endemic to the island of Kaua‘i. Both males and females are predominantly dark gray to olive above, whitish below. ‘Akikiki have pinkish legs and feet, and their short, slightly decurved bill also is pink. Usually found in pairs, family groups, or small flocks (8 – 12 individuals); during the non-breeding season ‘akikiki join mixed species foraging flocks. ‘Akikiki gleans and explores the bark and lichens and moss on trunks, branches, and twigs of live and dead ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha) and koa (Acacia koa) trees for insects and spiders. They usually nest high (9 meters) in the terminal branches of ‘ōhi‘a, but one female has been observed nesting in ōlapa on two occasions. Nest construction begins in early March, and continues into June; males occasionally help with nest building. Most nests contain two eggs, some contain only one egg. Both males and females feed chicks. Despite a long period of parental dependency, four cases of double brooding has been observed, with the male provisioning both the incubating female and the older chicks. Causes of nest failure include predation, likely by rats, poor female attendance, infertility, and hatch failure.

Distribution

Restricted to a 36 square kilometer (13.8 square mile) area of the Alaka‘i Wilderness Preserve, but very rare in the northwestern part of this range and appears to be undergoing a severe range contraction. Historically occupied high- and low-elevation forests, although by the 1960s was most common above 1,140 meters (3,750 feet). Subfossil remains suggest a prehistoric island-wide distribution.

Habitat

Mesic and wet forests between 600 and 1,600 meters (2,000 – 5,300 feet). Rainfall and topography varies across the species’ range, resulting in enormous habitat variation. Thus key habitat variables are difficult to quantify, however,

occupancy is correlated with large trees (i.e., canopy height) and canopy density. The montane forests of Kaua‘i are dominated by ‘ōhi‘a with a subcanopy comprising ‘ōlapa or lapalapa (Cheirodendron spp.) and ‘ōhi‘a hā (Syzygium sandwicensis). Common understory species include ‘ōhelo (Vaccinium calycinum), kanawao (Broussaisia arguta), ‘ōhā wai (Clermontia spp.), kāwa‘u (Ilex anomala), kōlea (Myrsine lessertiana), na‘ena‘e (Dubautia spp.), and pūkiawe (Styphelia tamieameiae). Occupancy is very low in areas invaded by non-native plants.

Threats

Disease. Mosquitoes likely are ubiquitous on Kaua‘i, and avian malaria and avian pox are likely the most important factors limiting the species’ distribution. To date, two of 22 ‘akikiki have tested positive for malarial antibodies, and were later resighted, indicating that some individuals have resistance or tolerance. No pox lesions have been observed.

- Habitat degradation. Pigs (Sus scrofa) and goats (Capra hircus) have contributed to the spread of non-native plants, but effects to ‘akikiki are unknown. Severe hurricanes in 1982 and 1992 heavily damaged native forests, possibly resulting in short-term reductions in arthropod food resources and long-term damage to forest structure

preferred by ‘akikiki. - Natural disasters. Hurricanes in 1982 and 1992 likely caused the death of an unknown number of individuals.

- Competition. Although little evidence exists, it has been suggested that competition with introduced Japanese white-eyes (Zosterops japonicus) and Japanese bush warblers (Horornis diphone) may negatively affect ‘akikiki. Non-native insects, especially yellow jackets and ants, may compete with or prey on the native arthropods on which ‘akikiki feed. The role of non-native insects in native Hawaiian forests is unclear.

- Predation. Predation by rats (Rattus spp.), on nests has been documented in at least two instances, and suspected in others. Rats, cats (Felis silvestris), Hawaiian short-eared owls (Asio flammeus sandwichensis), and barn owls (Tyto alba) occur throughout the forests of Kaua’i, and may prey on young and adults.

- Population size. Small populations are plagued by a variety of potentially irreversible problems that fall into three categories: demographic, stochastic, and genetic; the former are usually most problematic. Demographic factors include skewed sex ratios and stochastic factors include natural disasters. Habitat fragmentation exacerbates

demographic and genetic problems. Some of the observed infertility and failure to hatch may be due to these small population issues.

Distribution

Restricted to a 36 square kilometer (13.8 square mile) area of the Alaka‘i Wilderness Preserve, but very rare in the northwestern part of this range and appears to be undergoing a severe range contraction. Historically occupied high- and low-elevation forests, although by the 1960s was most common above 1,140 meters (3,750 feet). Subfossil remains suggest a prehistoric island-wide distribution.

Habitat

Mesic and wet forests between 600 and 1,600 meters (2,000 – 5,300 feet). Rainfall and topography varies across the species’ range, resulting in enormous habitat variation. Thus key habitat variables are difficult to quantify, however,

occupancy is correlated with large trees (i.e., canopy height) and canopy density. The montane forests of Kaua‘i are dominated by ‘ōhi‘a with a subcanopy comprising ‘ōlapa or lapalapa (Cheirodendron spp.) and ‘ōhi‘a hā (Syzygium sandwicensis). Common understory species include ‘ōhelo (Vaccinium calycinum), kanawao (Broussaisia arguta), ‘ōhā wai (Clermontia spp.), kāwa‘u (Ilex anomala), kōlea (Myrsine lessertiana), na‘ena‘e (Dubautia spp.), and pūkiawe (Styphelia tamieameiae). Occupancy is very low in areas invaded by non-native plants.

Threats

- Disease. Mosquitoes likely are ubiquitous on Kaua‘i, and avian malaria and avian pox are likely the most important factors limiting the species’ distribution. To date, two of 22 ‘akikiki have tested positive for malarial antibodies, and were later resighted, indicating that some individuals have resistance or tolerance. No pox lesions have been observed.

- Habitat degradation. Pigs (Sus scrofa) and goats (Capra hircus) have contributed to the spread of non-native plants, but effects to ‘akikiki are unknown. Severe hurricanes in 1982 and 1992 heavily damaged native forests, possibly resulting in short-term reductions in arthropod food resources and long-term damage to forest structure

preferred by ‘akikiki. - Natural disasters. Hurricanes in 1982 and 1992 likely caused the death of an unknown number of individuals.

- Competition. Although little evidence exists, it has been suggested that competition with introduced Japanese white-eyes (Zosterops japonicus) and Japanese bush warblers (Horornis diphone) may negatively affect ‘akikiki. Non-native insects, especially yellow jackets and ants, may compete with or prey on the native arthropods on which ‘akikiki feed. The role of non-native insects in native Hawaiian forests is unclear.

- Predation. Predation by rats (Rattus spp.), on nests has been documented in at least two instances, and suspected in others. Rats, cats (Felis silvestris), Hawaiian short-eared owls (Asio flammeus sandwichensis), and barn owls (Tyto alba) occur throughout the forests of Kaua’i, and may prey on young and adults.

- Population size. Small populations are plagued by a variety of potentially irreversible problems that fall into three categories: demographic, stochastic, and genetic; the former are usually most problematic. Demographic factors include skewed sex ratios and stochastic factors include natural disasters. Habitat fragmentation exacerbates

demographic and genetic problems. Some of the observed infertility and failure to hatch may be due to these small population issues.

Explore from Home

Did you know that ʻAkikiki can fly through outerspace? Not the ʻakikiki bird, of course, but an asteroid named ʻAkikiki after our endangered honeycreeper. You can learn more in this Audubon article about the ʻAkikiki asteroid.

Plans & Projects

Additional Resources

For more information and references visit the DLNR State Wildlife Action Plan factsheets. DOFAWʻs species pages and State Wildlife Action Plan fact sheets are provided for general information and are not meant to be a citable, original source of data. If you are a student, researcher, or writer looking for a citable source, please explore the references below or find other original data sources, rather than citing these webpages. The references below were provided by the authors of the State Wildlife Action Plan fact sheets at the time of drafting:

- Atkinson, CT, RB Utzurrum, DA LaPointe, RJ Camp, LH Crampton, JT Foster, and TW Giambelluca. 2014. Changing Climate and the Altitudinal Range of Avian Malaria in the Hawaiian Islands – an Ongoing Conservation Crisis on the Island of Kaua‘i. Global Change Biology 20, 2426–2436, doi: 10.1111/gcb.12535.

- Behnke, L. 2014. Habitat use and conservation implications for Akikiki (Oreomystsis bairdi) and Akekee (Loxops caeruleirostris), two endangered Hawaiian honeycreepers. M.S. Thesis. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

- Foster JT, Scott JM, Sykes PW. 2000. ‘Akikiki (Oreomystis bairdi). In The Birds of North America, No. 552 (Poole A, Gill F, editors.). Philadelphia, (PA): The Academy of Natural Sciences; and Washington DC: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

- Foster JT, Tweed EJ, Camp RJ, Woodworth BL, Adler CD, Telfer T. 2004. Long-term population changes of native and introduced birds in the Alaka‘i swamp, Kaua‘i. Conservation Biology 18:716-725.

- Hammond, RL, Crampton, LH, and Foster, JT. 2015. Breeding biology of two endangered forest birds on the island of Kaua’i. Condor 117: 31-40.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Version 2014.3. Available at: www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed May 2015).

- Scott JM, Mountainspring S, Ramsey FL, Kepler CB. 1986. Forest bird communities of the Hawaiian islands: their dynamics, ecology and conservation. Lawrence, (KS): Cooper Ornithological Society.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006. Revised Recovery plan for Hawaiian forest birds. Portland, (OR): U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Endangered Forest Birds of Hawaiʻi

The Endangered Forest Birds of Hawaiʻi