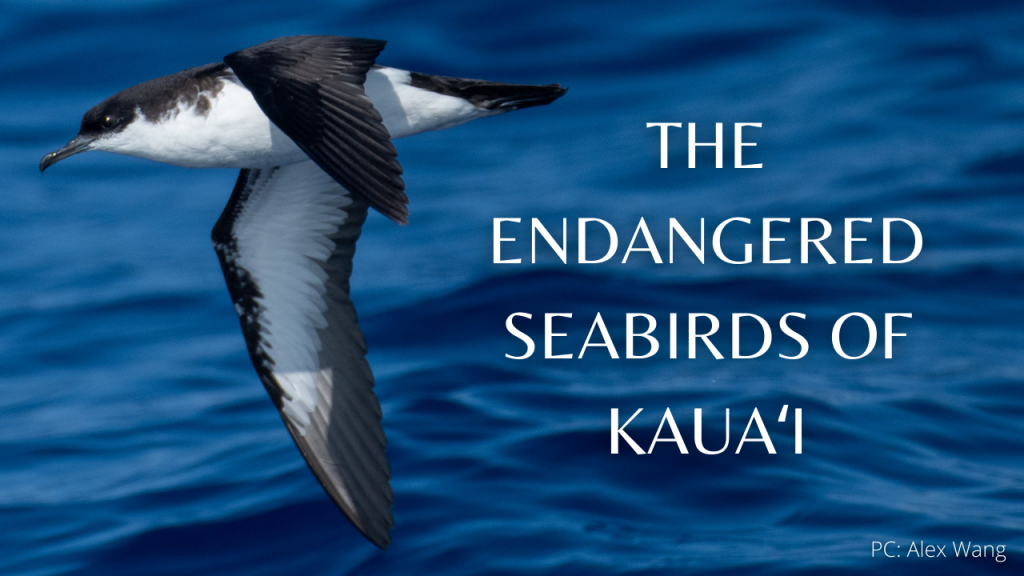

‘Ua‘u

Names

- ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi: ‘Ua‘u

- Common: Hawaiian Petrel

- Scientific: Pterodroma sandwichensis

Song

Conservation Status

- Federally Listed as Endangered

- State Listed as Endangered

- IUCN Red List Ranking – Vulnerable

Species Information

The ‘ua‘u or Hawaiian petrel is a medium-sized, nocturnal gadfly petrel (Family: Procellariidae) endemic to Hawai‘i. The name is derived from a commonly uttered call, heard at colonies. Adults are uniformly dark grayish black above forming a partial collar which contrasts with white throat, forehead, and cheeks; entirely white below except for black tail and leading and trailing edges of underwings. Owing to darkness of back color, the ‘W-pattern’ across back and upper surface of wings is not visible except in worm plumage. Bill black, and legs and feet mostly pink. Even during the breeding season, ‘ua‘u often feed thousands of kilometers from their breeding colonies, usually foraging within mixed-species hunting groups over schools of predatory fishes. They feed by seizing prey while sitting on the water or by dipping prey while flapping just above the ocean surface. In Hawai‘i, they feed primarily on squid, but also on fish, especially goatfish and lantern fish, and crustaceans. ‘Ua‘u nest in colonies, form long-term pair bonds, and return to the same nest site year after year. Colonies are now typically in high-elevation, xeric (with low moisture) habitats or wet, dense forests, although before the arrival of the Polynesians and their associated animals these birds nested in the lowlands, too. They nest in burrows, crevices, or cracks in lava tubes; nest chambers can be from 1 to 9 meters (3-30 feet) deep. Most eggs are laid in May and June and most birds fledge by December, although there are significant inter-island differences in breeding phenology; for example, the nesters that are earliest by more than a month reside at the summit of Haleakala Volcano. Both parents incubate the single egg, and brood and feed the chick. Birds first breed at five to six years of age.

Distribution

Nests among the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) including Maui, Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i, Lāna‘i, and possibly on Moloka‘i. Subfossil evidence indicates that prior to the arrival of Polynesians, ‘ua‘u was common throughout the MHI. At sea, they occur throughout the central tropical and subtropical Pacific Ocean.

Habitat

Nests in a variety of remote, inland habitats. On the islands of Hawai‘i and Maui, colonies are located above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) in xeric habitats with very sparse vegetation, with most nests in existing crevices in the lava. On Kaua‘i and Lāna‘i, and West Maui colonies occur in lower-elevation forests dominated by ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha) often with a dense understory of uluhe fern (Dicranopteris linearis). At sea, they are pelagic and occur over the open ocean.

Threats

- Historical hunting. Nestlings were considered a delicacy by Polynesians, and were harvested from nest burrows, including artificial ones constructed by the Polynesians. Adults were netted as they returned to colonies, and smoky fires were sometimes lit along flight corridors to disorient and ground birds.

- Introduced predators. Adults and chicks are susceptible to depredation by dogs, pigs, rats, barn owls, feral cats, and the small Indian mongoose. The presence of these destructive introduced animals, the main force behind population decline, has relegated the species now to nest only in remote interior areas, at very high altitude, or on islands that are predator-free.

- Feral ungulates. Feral goats (Capra hircus), mouflon sheep (Ovis musimon), and potentially axis deer (Axis axis) trample burrows and degrade nesting habitat.

- Artificial lighting. Street and resort lights, especially in coastal areas, disorient fledglings, causing them to eventually fall to the ground exhausted or increasing their chance of colliding with artificial structures (i.e., fallout) such as powerlines. Once on the ground, fledglings are killed by cars, cats, and dogs, or die of starvation or dehydration.

- Collisions. Adults and fledglings are susceptible to mortality from collisions with obstacles such as communication towers, utility lines, fences, and wind farm structures while commuting between inland nest sites and the ocean at night.

- Colony locations. The remoteness of colonies, as well as the habitat in which they occur (e.g., steep terrain or dense forest), complicates predator and ungulate eradication or control.

Learn more

Plans & Projects

Photos

Additional Resources

For more information and references visit the DLNR State Wildlife Action Plan factsheets. DOFAWʻs species pages and State Wildlife Action Plan fact sheets are provided for general information and are not meant to be a citable, original source of data. If you are a student, researcher, or writer looking for a citable source, please explore the references below or find other original data sources, rather than citing these webpages. The references below were provided by the authors of the State Wildlife Action Plan fact sheets at the time of drafting:

- Hawai’i Natural Heritage Program [Hawai‘i Biodiversity and Mapping Program]. 2004. Natural diversity database. University of Hawai’i, Center for Conservation Research and Training. Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

- Holmes N, Friefeld H, Duvall F, Penniman J, Laut M, Creps N. 2011. Newell’s Shearwater and Hawaiian Petrel Recovery: A Five-Year Action Plan. Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Honolulu, HI; Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Honolulu, HI; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu, HI.

- Hu, D. G.E. Ackerman, C.S.N. Bailey, D.C. Duffy, and D.C. Schneider. 2015. Hawaiian petrel monitoring protocol – Pacific Island Network. Natural Resources Report NPS/PACN/NRR–2015/993. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed May 2015).

- Joyce, TW. 2013. Personal communication. Scripps Institute of Oceanography, La Jolla, California.

- NatureServe. 2003. Downloadable animal data sets. NatureServe Central Databases. Available at:

https://www.natureserve.org/getData/vertinvertdata.jsp (March 10, 2005). - Simons TR, Hodges CN. 1998. Dark-rumped petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia). In The Birds of North America, No. 345 (Poole A, Gill F, editors). Philadelphia, (PA): The Academy of Natural Sciences; and Washington DC: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Regional seabird conservation plan, Pacific Region. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Migratory Birds and Habitat Programs, Pacific Region. Portland, Oregon.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Hawaiian dark-rumped petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia sandwichensis) 5-year review: summary and evaluation. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu, Hawai‘i.