Why Trees Are Important

Trees literally hold our island state together. They help define Hawaii’s sense of place, that special connection between our diverse cultures and the environment, the land and its people. While trees in urban areas may appear to have a different function than trees in the natural forest, they often are the first connection that communities have to nature.

Healthy Communities

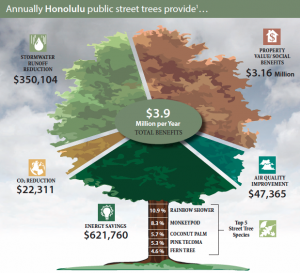

Each year 100 large, mature street trees help create healthier communities by removing 19 tons of carbon dioxide and 372 pounds of other air pollutants.

- Urban forests remove 882,000 tons of pollutants each year, an equivalent of $5.4 billion each year (US Urban Forest Statistics, 2018).

- Hawaiʻi municipal trees store 25,529 tons of carbon dioxide, remove a net 3,340 tons of carbon dioxide each year valued at $22,314, and manage 35 million gallons of stormwater runoff each year valued at $350,104 (C&CH, 2019).

- Annual gross carbon sequestration by urban forests (in conterminous US) is 36.7 million tons or $4.7 billion (US Urban Forest Statistics, 2018).

Better Business

Tree-lined commercial districts are better for business.

- People report more frequent and longer shopping and spend up to 12 percent more for goods when they shop in attractive settings (Wolf, 2009).

Healthy People

Tree-filled neighborhoods are safer, reduce mental and physical stress, and encourage people to spend more time outdoors.

Health & well-being

- Urban trees and forests reduce the harmful health impacts of air pollution and extreme heat (Wolf et al, 2020).

- Access to community forests is associated with improved mental health including decreased stress, depression, and anxiety (Hutsford et al 2013; Wolf et al, 2020) and improved physical health (Maas et al 2006; Wolf et al, 2020).

- Green spaces (particularly tree canopy) is associated with lower incidence of psychological distress (Bert & Feng, 2019).

- Loss of trees is associated with cardiovascular and respiratory disease (Donovan et al 2013; Wolf et al, 2020).

Education

- Having a view to green spaces increases test results and recovery from stressful experiences (Dongying & Sullivan 2016).

- Exposure to trees and shrubs during the school day is associated with higher test scores, graduation rates, and plans to attend four-year college, and fewer occurrences of criminal behavior. Large, empty landscapes were negatively related to the same test scores and college plans (Matsuoka 2010; Wu el. Al 2014; Kweon, et. al., 2017).

- School greenspace positively impacts student performance (Kuo et al, 2018; Kuo et al, 2021).

Energy Cost Savings

Trees provide shade and cooling, greatly reducing energy costs.

- Urban forests can reduce residential building energy used to heat and cool buildings by $5.4 billion/year (US Urban Forest Statistics, 2018).

Reef Protection

A healthy urban forest reduces erosion and filters pollutants significantly reducing runoff and the destruction of our valuable reefs.

Watershed Protection

Trees cost-effectively filter and improve water quality by reducing stormwater runoff and flooding. Trees in Honolulu intercept more than 35 mil. gallons of stormwater per year. This contribution is valued at more than $350,000 annually.

Health and Trees References

Wolf, K. L., Lam, S. T., McKeen, J. K., Richardson, G., van den Bosch, M., & Bardekjian, A. C. (2020). Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 4371.

Wolf, K. L., Lam, S. T., McKeen, J. K., Richardson, G., van den Bosch, M., & Bardekjian, A. C. (2020). Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 4371.

Astell-Burt, T., Navakatikyan, M. A., & Feng, X. (2020). Urban green space, tree canopy and 11-year risk of dementia in a cohort of 109,688 Australians. Environment International, 145, 106102.

Astell-Burt, T., Navakatikyan, M. A., & Feng, X. (2020). Urban green space, tree canopy and 11-year risk of dementia in a cohort of 109,688 Australians. Environment International, 145, 106102.

Takano, Nakamura, Watanabe (2002). Ur ban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces.

ban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), (2008). Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), (2008). Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands.

Leung, W. T. V., Tam, T. Y. T., Pan, W.-C., Wu, C.-D., Lung, S.-C. C., & Spengler, J. D. (2019). How is environmental greenness related to students’ academic performance in English and Mathematics? Landscape and Urban Planning, 181, 118–124.

Leung, W. T. V., Tam, T. Y. T., Pan, W.-C., Wu, C.-D., Lung, S.-C. C., & Spengler, J. D. (2019). How is environmental greenness related to students’ academic performance in English and Mathematics? Landscape and Urban Planning, 181, 118–124.

Donovan, G. H., Butry, D. T., Michael, Y. L., Prestemon, J. P., Liebhold, A. M., Gatziolis, D., Mao, M. Y. (2013). The Relationship Between Trees and Public Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(2), 139-145.

Ulrich, R.S. (1984). View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420-421.

Nowak, D. J. (2002) The Effects of Urban Trees on Air Quality.

Nowak, D. J. (2002) The Effects of Urban Trees on Air Quality.

Hawaiian Electric (HECO), (2014). Planting the Right Tree in the Right Place.

Hawaiian Electric (HECO), (2014). Planting the Right Tree in the Right Place.

Kuo, F. E., Taylor, A. F. (2004). A Potential Natural Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence From a National Study. American Journal of Public Health, 94(9), 1580-1586.

Matsuoka, R. H. (2010). Student performance and high school landscapes: Examining the links. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97(4), 273-282.

Taylor, A. F., Kuo, F. E., Sullivan, W. C. (2002). Views of Nature and Self-Discipline: Evidence From Inner City Children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1-2), 49-63.

Berto, R. 2005. Exposure to Restorative Environments Helps Restore Attentional Capacity. Journal of Environmental Psychology 25, 3:249-259.

Shibata, S., and N. Suzuki. 2002. Effects of the Foliage Plant on Task Performance and Mood. Journal of Environmental Psychology 22, 3:265-272.

Lohr, V. I., C. H. Pearson-Mims, and G.K. Goodwin. 1996. Interior Plants May Improve Worker Productivity and Reduce Stress in a Windowless Environment. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 14:97-100.

Find more messages and statistics at the Vibrant Cities Lab website.